We are on there…

“Improve general aviation safety” is on a recently issued National Transportation Safety Board list of ten things that it wants to do. Funny they should mention that. It was on my father’s list when he started Air Facts in 1938, it has been on my list since I joined him in 1958, and I guess you would now say that it is on my bucket list.

Over the years, the government has taken occasional interest in general aviation safety. When Elwood “Pete” Quesada was appointed in 1958 by President Eisenhower to be the first administrator of the just-formed FAA, he was astonished by the general aviation safety picture. Pete’s aviation career had been military and he had no idea what was going on with us. He had to resign his three star general rank to head the FAA because the charter said that only a civilian could be the administrator, but he was still an Air Force general at heart.

Plain-spoken to the point of being blunt, Pete decreed that general aviation safety would improve by 25-percent in the first year of his tenure, by his order. Nobody but Pete thought that could be done and in spite of some hastily drawn up safety initiatives, nothing changed very much. Nor has there been any revolutionary change since.

Lumping general aviation safety together is an accepted practice but it is not realistic. The activities are too diverse and need to be considered separately. There is instructional flying, recreational flying, agricultural flying, private air transportation flying and professional flying. The airplanes range from ultralights to intercontinental jets.

Even in the same area, different airplanes have varying accident rates. The only safety concern that spans everything is crashing but the frequency of and reasons for the crashing vary widely according to the type flying and even the type aircraft flown.

In each area, the safety record we get is a product of the rules, the pilots involved, the airplanes, and the environment in which the pilots fly those airplanes. To make any change in the record, one or all those elements would have to be modified.

The worst accident rates are found in the recreational operation of experimental airplanes. When compared with other types of flying the rate truly stands out. But that kind of flying is totally different from, say, flying for personal transportation.

The certification standards for airplanes create a minimum acceptable level of handling qualities, performance and structural integrity. Many experimental airplanes equal or better the certification standards but many do not. If experimentals had as good a safety record as certified airplanes that would tell us that the whole certification process is without value.

The pilots are different, too. Pilots flying for recreation are looking for enjoyment and the pure fun of darting around in the sky. Which is to say that, in large part, their airplanes are toys that they play with. Play too hard and problems arise.

The environment is different, too. The recreational use of airplanes tends to take place at smaller airports, with less margin for error. That is true whether the airplane is certified or experimental.

The record in experimental airplanes and other recreational flying is just what happens in the activity. Noise can be made about making the record better, but it can’t be done without screwing up the wonderful freedom of that kind of flying. The risk is higher but if folks are free spirits, and want to take chances, that’s their choice.

To some pilots, taking that risk is part of the thrill of the activity. Many such pilots look at safety-conscious pilots as goody two-shoes. Maybe, though, some of us have gotten our risk thrills elsewhere. My father was a great proponent of aviation safety and got his youthful kicks by standing up on the seat of his motorcycle and racing trains. He had the scars to show for it, too. I know of another young Collins who raced cars on the back roads of Alabama, at night, with no lights on, and with a snoot full. No scars there, however.

The point is, you can be a daredevil elsewhere but still bring a cautious attitude to flying. Actually, that is necessary for survival because crazy or sloppy flying is much more likely to be lethal than crazy or sloppy driving.

One thing that is the same for all are the pilot certification standards. They are uniformly slack in all flying that is not done for hire. The same thing is true for proficiency maintenance regulations. Our flying is probably the least regulated activity out there that has such a high potential for lethal outcomes.

In fact, little is required of pilots and anybody who can pay the money can get the certificate and stay legally current. And most pilots do well until some egregious flying sin results in a wreck or wrongful flight into regulated airspace. Then the tentacles of the bureaucracy will try to strangle any remaining life out of the pilot.

My main area of interest has always been transportation flying. There is plenty of fun, or challenge, there and the safety record is a reflection of how pilots manage the risks.

Weather is a big factor and when pilots try too hard for the reward of being there on time, the risk goes up. There is no such thing as hard or easy IFR but there is weather that is beyond the ability of a lot of instrument pilots. A really well-trained and proficient pilot flying a well- equipped and perfectly maintained airplane can address most of the weather challenges but if there is any weakness in any area… Boom! The risk goes out of sight.

The record in transportation flying is what it is and to find any improvement, some of the utility and reward would have to be legislated out of the activity. I have always thought that the only practical improvement could come from a modification of the night IFR training and proficiency requirements.

The way it stands now, you can fly passengers at night in low IFR conditions as long as you have completed the required night takeoffs and landing in the past 90 days. There is no night IFR training requirement. It is no wonder that the record in night IFR flying is one of the worst in certified airplane flying. Pilots need to be trained in night IFR and need to maintain proficiency if they are going to engage in the activity.

Some of the other training emphasis apparently doesn’t do an adequate job of preparing pilots for real sky flying. That is one reason that the majority of fatal accidents are related to two things: low speed losses of control and weather.

In training, the emphasis is on teaching stalls, not on teaching pilots how to fly to avoid stalls. Stalls done at altitude are nothing at all like the lethal low altitude stalls. The visual sensations are different, the feel is different, and the departure from controlled flight is different.

I flew my P210 for 28 years and almost 9,000 hours. I never stalled the airplane and I never even came remotely close to an unintentional stall. I never heard the sound of the stall warning system. I knew how to fly the airplane to avoid stalls. Someone once told me that I flew it gently. That was the goal. That should also be the goal as we teach new people to fly.

Weather is a whole different matter. It is not a “thing,” and even the best educated meteorologists learn something new every day. If they don’t, they are pretty lousy forecasters.

Pilots learn to read forecasts and reports and are tested on the ability to do so. That is easy. What is more difficult is dealing with changing conditions that might not match the forecast or report. The best thing a pilot can do is to recognize that what you see is what you get and if it doesn’t look good, don’t mess with it.

There are plenty of seeming aberrations in accident statistics. Some are a result of people manipulating numbers to make them suit a need. Most, though, are not aberrations and have a valid reason for being.

Take the Cirrus as an example. The SR-20 has a good accident record, the more powerful SR-22 is not so good. Why? Pilots who buy the faster and more expensive airplane likely try harder to make it deliver. In pushing for success, they take more risks.

Any improvement in general aviation safety would be wonderful but it is not likely to come because nobody wants to mess up the freedom and utility that we have now. To make general aviation flying markedly safer, you’d have to smother it with regulations.

What we have now is a voluntary safety system. There is all manner of information out there for pilots who want to fly safely. The trouble is, the pilots who go for that information don’t really need it. The pilots who do need to read and heed the safety sermons don’t go for it.

So flying winds up as safe as an individual cares to make it. The mechanics of it are not hard to learn. Developing a healthy state of mind in relation to flying is more complex. It is as much about keeping the pilot’s and the airplane’s attitude in the right place as anything else.

In closing, one more word about accident statistics: The government doesn’t have much of a clue about the hours flown in general aviation. Any change in accident rates has more to do with FAA’s wild guesses about hours flown that anything else. That is why accident rates seem to jump around from time to time.

An example of this came when piston airplane flying fell of a cliff in 2008. The FAA published reports on daily accidents and we knew flying had all but stopped because accidents had all but stopped. The bad/good news in 2011 is that accidents are almost back up to pre-recession levels. That means flying activity is burgeoning. Too bad that is such a good indicator of flying activity.

- From the archives: how valuable are check rides? - July 30, 2019

- From the archives: the 1968 Reading Show - July 2, 2019

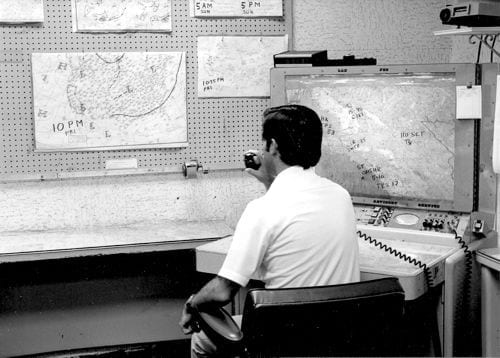

- From the archives: Richard Collins goes behind the scenes at Center - June 4, 2019

GREAT POST DICK. YOU COVERED IT ALL.

Reminds me of the line from “Cool Hand Luke” — we got to get your mind right.

I fly, and I also sail. Two activities with common denominators of lots of squandered money, and safety. Like flying, the mechanics are not that difficult, but there is a lifetime of finer points to learn. And the capability of pushing yourself into a lethal corner if your mind isn’t right. And it’s the same main element — weather — that you can choose to defy. And has killed an awful lot of people over the years. There is a stubborn minority that chooses to be cavalier about, ignorant of, or unmoved by real risk.

I wish I knew the solution. My thought is that the culture of GA needs to change fundamentally. Even recreational flights need to be approached with a high degree of professionalism. After all, that $100 hamburger run can kill you just as surely as the business trip.

I enjoyed your article. It reinforces what I learned as a young teen and airport kid in the 50’s; “There are old pilots, there are bold pilots, but there are no old bold pilots”. Since I practically lived at the airport, which was 2,600 foot grass, I saw more than my share of accidents. Most were pilot errors like the 85 Swift that attempted to take-off with 2 big guys and full tanks and never made it out of ground effect. Then there was the man in his 170 that was the victim of his seat sliding back on take-off which, I assume, contributed to the AD some years later.

Flying will always be dangerous for those who are not risk aware. I’m not sure that reams of new regulations would change that.

I live in Santa Fe , play at AirPort a lot. This Ap. Used to 200 take offs daily , now 30 if lucky thus is a reflection of the sorry oconomy . AV gas here $7.00 gal. looks like G.A. may be gone here soon. This is a extreemly wealthy place …. Sad Deal

“Flying is as safe as you make it.” Couldn’t agree more. This open-ended, you-decide attitude is kind of out of step with 21st century thinking it seems like. We want to strictly define the limitations of what can and can’t happen. But the flexible nature of GA just doesn’t fit into this–but that’s exactly why we all love it!

Excellent article (as are all by Mr. Collins).

A lot of good helpful information is readily available these days, information we can all learn from no matter how many or how few hours we have. I’m talking about articles, tips, accident reports, etc.

Working at a GA airport, I talk with pilots all the time who don’t take the opportunity and spend a little time to keep learning.

Dick,

Since something on the order of 85 percent of the accidents are caused by “pilot error” there’s obviously a disconnect in how we’re training new pilots. At the SAFE Pilot Training Reform symposium in Atlanta, there seemed to be a consensus that we have to be better about teaching pilots risk assessment and mitigation. When a pilot loses control in inadvertent IMC, the cause of the accident is more likely one of a decision made earlier in the flight and not only his inability to “fly” the airplane. We have to continue to teach basic skills, but also to ingrain the concept of considering the risks involved in every flight and making the prudent decision about whether the need to make the flight justifies accepting the attendant risks.

Keep up the good work.

Dick,

I have been reading your thoughts on this subject for years and you have been consistant and, I believe, accurate.

However, I wonder if we would not be better off learning from the masters rather than the self-proclaimed experts. The masters I refer to are, of course, birds.

I watch them fly without checklists, in crowded skies, on short strips and in bad weather, but have yet to see one crash (ok, the occasional hit into a manmade window, but..). And yet they seem to get good utility and even make a living at it. What do they know that we don’t? Is it the simplicity of the flying machine coupled with low wing loading and almost unlimited landing sites? Or just their lifestyle that doesn’t require that they be at a particular destination at a particular time?

We started out trying to emmulate them and we did a masterful job of understanding the mechanics of flight. Maybe we stopped short at understanding the mental dynamics.

Yet even birds can get vertigo, in the early 1960s I was an Air Force Tower Controller at Laughlin AFB.

On my way to work one morning I noticed a large number of dead birds all around the theodolite. Later the state people arrived an took a few birds for testing, their conclusion was that all the birds were night flyer’s and the theodolite, shining into a low haze layer, caused the birds to believe they were inverted and they lost control trying to fly upside down. No moon that night.

Test showed all died of impact injuries.

Believe it or not.

Dick,

Agreed!

Are you back in the saddle yet with an LSA taildragger ?!!??

Not back in the saddle with a Cub as yet, but maybe someday.

Attending the safety seminars made available by the FAASTeam provide an indication of how many pilots are really concerned with improving and updating all of their flying skills. It has been a disappointment to me to see so many pilots who do not avail themselves to the safety training resources that are available.

Dick, you are right on point, as you usually have been for the decades that I have been reading your articles. However, I’ll bet you DID hear your 210s stall horn somewhere along the line, landing at a short and/or obstructed runway…..

I used to fly a T210 out of 2200 feet, and you really wanted to hear it right before touchdown, especially if the runway was wet.

Dick, you are right on the money. This is about the clearest writing I have seen on this subject. The key words are “Voluntary” and “Free”. It is interesting to note that as we wring our hands over the sorry state of safety in GA flying, we are also bemoaning the falling numbers of pilots getting a certificate. In our zeal to “do something” to improve safety we run the risk of driving people away from flying. As you note “GA safety” had been a top concern of the FAA since its inception. The only area that has been materially affected in a positive way is corporate flying. I agree that stall training bears no resemblance to the real thing. To bring more realism to this realm requires performing stalls around 1000 feet AGL. This is classified as aerobatic flying. Can today’s lower cost simulators do a credible job here? Of course, that is a subject of your stall training debate.

It is difficult to argue against making something safer against serious injury or death, but this road always leads to laws and regulations that stifle if not kill the activity and more importantly development of the activity allowed by new technology and designs. So, where is the limit?? And why is it more important to make general aviation safer than say mountain climbing, or riding motorcycles. Where I live you can ride a motorcycle without a helmet, but are required by law to wear a seatbelt to drive a car. Wearing a helmet and using a seatbelt are certainly good ideas, but the risk of not wearing a helmet on a motorcycle is much greater than not using a seatbelt in a car.

If Pilot Error is to be reduced …. what is the goal? Certainly not zero because all pilot’s are human and habits are hard to break. If you have “get home itis” in flying you certainly have it driving as well. And how should this be accomplished? For my 2 cents worth, it needs to be accomplished in inexpensive simulations that mimic typical pilot error and results…hear, see, experience…maybe contests at the EAA Chapter level, or all Fly Ins with nationwide results leading to prizes to the winners such as AOPA and EAA give away to their membership.

GA is already overburden with regulations that are unnecessary, e.g. 3rd class medical requirements. Does anyone not believe this class of medical could be eliminated, relying only on having a driver’s license, subject to a specific list of illnesses that require medications that actually impair flying capability. We’re chipping away in this regard, but there are certainly many many opportunities to eliminate or significantly revise existing regulations that are burdensome to GA and do little if anything to really make it safer.

How safe is safe enough???

“To make general aviation flying markedly safer, you’d have to smother it with regulations.”

The risk is worth it, now more than ever the last thing we need is to reduce the freedom and utility of GA. You can sit on your bed and never have any risk of crashing (you’d just die of poor health), but then you aren’t really living, are you?

To me, the accident statistics aren’t that bad for the average GA pilot who accounts for the following:

– Poorly maintained airplanes are likely to break…

– Fuel is REQUIRED to fly…

– Weather can make it hard to see…

– Flying near the ground makes “contact” more likely…