1 min read

In our second installment of The Great Debate, Editor Richard Collins asks about the controversy surrounding airline pilot training. Share your opinion below–Richard will respond to some comments too.

Question: The loss of control of an Airbus A330 over the Atlantic has led to calls for more hands on (as opposed to autopilot) training for airline crews. This subject has recently gotten a lot of attention in the press. Much ado about nothing or a real problem?

Latest posts by Richard Collins (see all)

- From the archives: how valuable are check rides? - July 30, 2019

- From the archives: the 1968 Reading Show - July 2, 2019

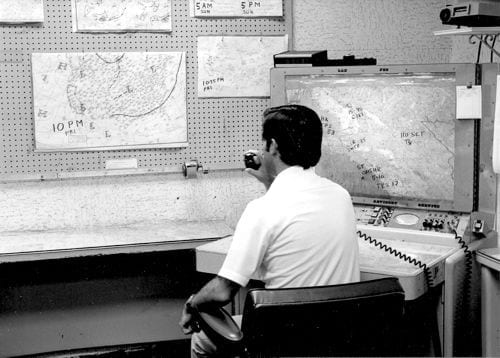

- From the archives: Richard Collins goes behind the scenes at Center - June 4, 2019

I agree, there should be more hands on training. Although I am only a PPL I have always aspired to be an airline pilot. The more I think about it, the more I actually think – do I really want to? It seems as if now, autopilot takes much of the fun out of flying. I think instructing would be much more fun and a lot more “hands on”.

Dear Dean I agree 100% with your comment I fly to enjoy and fell the airplane.

the 22,000 airline pilot flying with auto pilot 95% of the time routinely, is the same as a bored bus driver

I believe any of the three pilots would have passed a hands on stall recovery demonstration test. The issue appears to me none recognized a plugged pitot tube symptom. We have achieved a great safety record by using the automation available to us. Let’s keep that, and add recovery from surprise automation upset to training. There have been many examples of how that can happen to select from.

I agree with Gary N.. Nat Geo did a documentary on this mishap and several crews were tested on this scenario. Without knowing what situation they were going to be put into, every one of them caught the discrepancy and disconnected the AP. Advanced automation like that of the Airbus line is essential to air carrier safety. Hopefully we can learn a great deal about automation management and human factors now that we have more data on this mishap.

You got it–this accident was a failure of autopilot management as much as it was a failure of “stick and rudder” flying. Pilot of airliners these days are systems managers, and I think that’s OK. They just need to know when the system isn’t working. And can we pass a law that bans the AP from writing about complicated aviation subjects?

Hi Jerry: Sensational writing about aviation subjects has been and always will be a problem. Just look at today’s coverage about the terror threat from small airplanes.

It all comes down to applying common sense to any and all training. Then, one must consider the fatigue factor involved in a long flight. Without proper training and good common sense to handle the variables thrown at you, all is lost.

The idea that pilots shouldn’t use autopilots as much as they do is unrealistic, I think. Modern airplanes need autopilots to fly–just try to hand-fly an airplane at 35,000 ft.

The issue that isn’t getting discussed enough is the way the autopilot failed here. It seemed to pretty much throw up its hands and say “you got it!” You would think there might be a safer way to alert the autopilot monitors (pilots) that there was an airspeed problem. Or maybe a 5 second warning before disconnecting. I hope that this accident results in smarter autopilots and not just more simulator stall training.

I think that most airline pilots have pretty good stick skills and autopilot skills.

What we have here is a failure to recognize what went wrong and how to deal with it. I’d bet it’s more of a training issue than just learning how to shut off the autopilot. Perhaps these guys never had training with this senario.

And, an airliner is easy to hand fly at 350 for several hundred miles, just gets boring, as does a small plane. I’ve done both, but prefer the autopilot.

Larryo

As an RJ pilot, I’m completely comfortable hand flying, but would be reluctant to fly a jet with a broken autopilot (legally deferred) more than 2-3 of the 4-6 flights I typically do daily. Hand flying a high performance jet with passengers is demanding. It is safer to use the autopilot because (1) it gives the pilot more capacity to monitor the airplane with, & (2) using the AP leaves a pilot less fatigued at the end of a flight/day. We forget these advantages when decrying ‘too much automation’.

OTOH skills/ability to hand fly your jet in an emergency shouldn’t suffer. Basic instrument skills (pitch-power relationships) during pitot-static failures aren’t taught in the simulator, but perhaps should be.

The Air France pilots had a tricky situation. Did they know that stall warnings would stop if the airspeed got too low and the AOA got too high? That’s what the A330 does! They lowered the nose, got the stall warning, then raised it and it stopped. This was a cycle they continued. Then went against instinct and depended on the warning system they misunderstood. Our course, bad airmanship set up this scenario.

Automation is complex, and pilots must have a good understanding of it and ability to manage it, and still must be able to hand fly in abnormal and emergency situations. Lack of automation understanding and lack of hand flying proficiency in abnormal situations pinpoint the issues more accurately.

In my opinion, it’s definitely a major issue among airline pilots. It’s actually not about autopilot flying the plane or not. It’s all about having the basic flying skills and really understanding the automation systems that are in-place.

The Air France pilots had a tricky situation, no doubt. However the fact that none of them appeared to have a really completely solid understanding of the systems, of what was real, and what wasn’t is really disturbing. They had ground speed which was always correct. They had altitude which could be corroborated with reasonable accuracy via GPS. And when they had descended to below 15K feet, the difference between indicated airspeed and ground speed should have started telling them that something was amiss. In my mind, they should have been able to get the plane under control.

As a GA pilot, I find it “really scary” that they didn’t seem to have the training or the skills to figure it out. Yes, the A330 systems are complex, but the physics of flight is always the same regardless of airplane type. We’re taught that what happens to an airspeed indicator in the event of a pitot-static failure…it turns into an altimeter. So ignore it and go on to what is working. And the fact that it wasn’t exactly trained is also disturbing. Do today’s airline pilots only know what’s in the training manual and taught in the Sim?? Isn’t there lot’s more to know and to learn? In 36+ years as a pilot, I’m constantly trying to learn more about flying and the equipment that is in use.

Abnormal situations are going to happen in airplanes. That’s the nature of complex systems. The folks up-front should be the master of those systems and completely understand their capabilities and limitations.

I am an GA (now LSA) pilot and My CTLS has an autopilot, the first one I have ever had. I find that the autopilot makes cross-country flying less tiring. Yes, I use it at altitude and do not feel it has affected my flying skills one bit. However, the airlines seem to force then issue by insisting that their pilots use the autopilot for almost every part of the flight–which does not give the pilots much opportunity to maintain manual flying skills.

Given a choice betweena 2500 hour Alaskan bush pilot and a 20,000 hour airline pilot, I think that most would agree that the bush pilot more likely have the better touch on the controls. Airline pilots seem to be becoming more like computer graphics artists like me; more a manager of elaborate systems than a skilled artisan. Put a pen or paintbrush in my hand, and I’m not better than a child. Stick an airline pilot in a mountain valley on a windy day, and would he become like a child at the controls?

Maybe its time to bring back the third flight crew member, as a systems manager rather than flight engineer. He/she would specialize in systems monitoring and troubleshooting. This would leave the pilots free to fly the plane while the systems manager communicates, navigates, and runs through the checklists.

And bring back the yoke. Sidesticks are for fighters and video games.

I view the auto pilot as a necessary and very important “aid” to flying. It reduces workload, allows time to check maps, charts and approach plates and generally helps to relax the flying activity. Having said that I believe that it is ONLY an aid and not a substitute for aircraft control, awareness and piloting skill.

I never engage the auto pilot until I’m well underway on departure and then turn it off when I’m well established into the descent and prepared for the approach either IFR or VFR and the circuit entry and landing. So I basically use the auto pilot only for the cruise section of the flight. The real flying ie., take off, departure and descent and landing is hand flown. My IFR renewals however are done entirely without the aid of the autopilot so that I can demonstrate to my Instructor that I know what I’m doing and can handle the aircraft. (I hold ME Command Instrument rating and a CPL and currently mainly fly a C T210 with intermittent bursts of BE55 and 58, I used to operate a BE65 B80)

I hope this helps.

best wishes

Tony

Well said Tony…I totally agree an auto pilot is an “Aid” and I have always used them as you describe. I had an L1011 head check pilot for a now closed airline sign me off for my CFI in exchange for his seaplane rating which once I was a CFI I trained him in. He was very bad on the controls and was so emabrassed at his manual flying skills he purchased a single engine small aircraft the next day! This senior check pilot claimed he lost his skills by using the auto pilot so much as was standard procedure for all airline pilots.

The only commericial pilots I know that still can fly stick and rudder own their own aircraft and or at least fly smaller planes on a regular basis.

Complex aircrat with lots of systems is just like large sailing yachts… if you can sail a dinghy you can sail a large yacht once you know the systems… but if you sail only large yachts you will find it very difficult in sailing small boats….. the best sailors come from having excellant small boat skills and I believe this to still be the case in aviation.

I think the question should be what do US airlines and the military do differently? They all fly similar transport catorgory equipment in sometimes very demanding situations. Could this accident been as simple as overlooking the basic first duty of ‘fly the airplane’?

From things we have heard, there might some change in emphasis on autopilot use and recovery from low-speed situations. This is brought on by both the regional Bombardier turboprop accident and the A330 accident. There will be more emphasis on understanding the systems and the elements of maintaining control when up to your ears in alligators. And Shahryar, having a sidestick or a yoke doesn’t really make a difference. I have flown a lot more with a yoke but prefer a sidestick.

Some good comments.

One thing, while the autopilot is a NICE safety feature, the plane (jet) can be flown without, and a competent crew should be able to dispatch without. If the weather or situation is such that it is not safe, simple don’t take the flight.

I’d have no problem dispatching is all three autopilots were inop for a 14 hour flight overseas, but we always have 4 pilots on board and 2 at the controls. Inconvenience, yes, impossible, no.

Our company (major US carrier), never required that we do all the flying on autopilot, but there were some situations where it was required, like the Cat II and IIIa and b landings. Enroute, while boring, was not a requirement.

Yes, well all need basic flying skills and the ability to recognize a slow speed situation that can lead to issues, autopilot or not. I have seen a lot of situations where the pilot forgets what is set, autothrottles off and the speed gets slow. I could argue to back up the automation with following thru on the controls. If the throttle don’t come up, you push them up.

I was never a Bus driver so can’t comment on what the situation was with Air France, but the Boeing stuff seems to work a lot better. I can’t imagine that happening in a Boeing. (but been wrong before).

It appears that the Air France accident was just a case of not fully recognizing the initial failure and the understanding system responses. This is not a problem of basic airmanship, but a learning experience which will/should result in expanded simulator scenarios. There can be no question that automation has improved safety in the airlines, the results are obvious.

It doesn’t appear that it has helped GA to the same degree. Maybe we don’t have enough data yet to come to that conclusion though.

Airline pilots are trained to fly both with and without an Autopilot. This is part of their regular mandated training.

We private pilots are trained also to fly both with and without Autopilot assistance. In our regular biannual training and instrument testing we are also trained to use both.

In my own flying I certainly use an Autopilot. I feel it is a great safety tool when flying cross country. Sure, when you are just beating around the patch fly without “George”. However if you fly cross country an Autopilot should be considered a no-go item.

Try flying 24 hours in a week from Montreal to Ft. Worth to Tulsa,Nashville and Wichita. Try flying in and out of airline hubs and you’ll soon see the value of good Autopilots.

I am quite convinced that I am a better and safer pilot because of my use of an Autopilot. My log book reflects that I fly 55% of my hours cross country and for business purposes. I also fly a significent amount of IFR, sometimes as much as 9 hours a week in the clag.

I always file IFR and shoot an approach even in VFR conditions, that assures practice.

One last word, don’t log IFR time if you are not in IFR conditions. It’s your life your fooling with by cheating!

The “march of automation” is the reality of the modern era. The problem, as I see it, is that the FAA, the Airlines, and the manufacturers are so enamored with their “gee whiz” automation that the training now concentrates on “how to fly the automation” while ignoring other important training priorities. The strain on training resources when training people to fly new automation is considerable.

There is only so much simulator time alloted to training pilots new to the aircraft, and the FAA is going to ask why a pilot used more than the programmed hours of training to get qualified. I have had this discussion with FAA POI’s, who wondered why a fellow who passed his checks took more time than the regulatory/programmed minimum. I said it was, “because his instructors and I thought he needed it”. That answer seemed to confuse them.

Let’s face it, simulator time is expensive and everyone has to learn how to fly the automation, which is not exactly a slam dunk, and you are not going to pass the check if you can’t make the automation do what it is supposed to do. If other priorities are not required, they are not likely to be included, because it would extend the training time. The industry is paying the price for that attitude.

I am aware of a pilot taking a rating check in the FAR 142 environment, who decided to disengage the automation and successfully complete the maneuver on basic flying skills, who flunked that maneuver, even though is was accomplished successfully as hand flown. What does that say about the regulatory authorities attitude about basic flying skills?

Also, many airlines, based on FAA and manufacturer guidance; discourage their pilots from hand flying the aircraft. As a result, their hand flying (and thinking) skills do not get developed and/or will get lost after a period of time flying automated aircraft.

I was a DC-8 Check Airman for a Carrier where the senior people got checked out and flew the DC-10 for two years. When they came back to the DC-8, and some of these people had 20,000 hours in the DC-8, it was clear that two years on the DC-10, not necessarily as highly automated as the current generation aircraft, had caused their hand flying and thinking skills to seriously deteriorate. Getting some of them requalified was quite a task. Not only did their instrument scans seriously deteriorate, but they also had fogotten how to fly and think ahead of the aircraft at the same time.

A few of them required more simulator time than we normally allocate to initial pilot trainees on the DC-8. It was quite an experience for me to see Captains whom I had flown First Officer for, who could make the DC-8 do exactly what they wanted the bird to do, to a situation where, as one of them told me, when I was providing line supervision “I couldn’t find my butt with both hands”.

I can’t imagine what that must be like when confronted with the failure of the autopilot (or crutch, if you will) at night, overwater, in the vicinity of convective weather, without an understanding of how to hand fly the aircraft, in that situation, on instruments.

If they had just maintained power, wings level and the cruise pitch attitude for several minutes, the pitot tubes cleared themselves out, and it would have just been an interesting incident, instead of an accident.

The other factor that I see in this accident is that the obsession within the Air Carrier community with “Approach to Stall Training”.

When confronted with an actual stall, such training is worse than useless. This is not the first time that an aircraft has been lost because a crew tried to recover from an actual stall using “approach to stall” recovery techniques. Airborne Express lost a DC-8 on an out of maintenance test flight on Dec. 12, 1996, for the same reasons.

In approach to stall training, the recovery is initiated at the first aerodynamic indication of a stall (onset of the stall buffet or in some aircraft a “stick shaker”). At buffet onset the aircraft is several knots below stall speed and also below stall pitch attitude. The pilot mearly applies power and reduces the pitch attitude below the buffet onset, and flies out of the stall.

An actual stall is a completely different animal. When the pitch attitude continues to increase, the aircraft stall buffet will continue and intensify, until the nose will “break”.

This is where the nose of the aircraft pitches down without (or in spite of, as in the case of the Airborne Express, Colgan 3407 and AF447) control input from the pilot. Once the stall breaks and the nose pitches forward, the pilot must pitch the nose of the aircraft lower (pitch attitude reduced) and continue to pitch lower, until the stall buffet ceases.

The pitch attitude for recovery fromt he stall may be lower than the pilot has ever seen. Max power application at the break is not crucial to the recovery from the stall, that is handled almost entirely with pitch attitude. However, appropriate application of power is important to keep the engines operating and for recovery back to level flight at the appropriate airspeed and altitude.

The smooth recovery from the stall may be initiated with appropriate power and pitch control. The pitch down attitude that may be required in a swept wing aircraft (expecially in the clean configuration) to recover from the stall may provide the illusion that you are pointed straight at the ground, and may cause the speed to build up fairly rapidly, so a smooth but positive recovery is required. Reducing pitch and appropriate application of power is necessary for a smooth recovery.

Having max power on the aircraft at the stall, can contribute to the speed build up after the aircraft is clear of the stall at a low pitch attitude.

The only pilots I know who have experienced the actual stall are those who perform the original testing of the aircraft or those who perform out-of-maintenance test flights.

Most simulators are not programmed or capable of realistically simulating the actual stall, because such a maneuver has never been required since the first aircraft specific simulators have been built.

A lack of priority in the development and application of instrument flying skills and the training experience and knowledge of what should be done when the main instumentation fails, is what got AF447 into a stall. It was the lack of understanding of how to recognize that they were in an actual stall and how to recover from that actual stall is what caused them to end up in the Atlantic.

Tom Olsen

listen to what AF pilot union said about the crash”the instruments got haywire”clearly trying to mislead the situation.

I believe in this accident,both pilot and airline are to be equally blamed.

Clearly more stringent rules and procedures are needed to be formulated by regulatory authorities for training pilots,so that the skies and lives of people are much safer.

Tom, you’re absolutely right. Especially with your comment “An actual stall is a completely different animal”. It can be a bit, or a lot, scary, even in a small plane. One thing I’d mention though, is that if the flight, such as it is, isn’t completely coordinated, the “break” you mention will be to the right or left as well as down. So, along with nose down, opposite rudder is important to straighten things out and avoid a possible spin. That left or right break is, of course, the beginning of a spin, at least as best I understand. Great post Tom.

Great debate Dick. Glad to have you back and “untied”.

This discussion is a useful learning expirence for pilots of all types (part 99,135 and 121).

No, I don’t think pilots today have an autopilot addiction. Actually the A/P flies the plane better than a pilot can especially at high altitude near MMO and stall. Autopilots are needed for these operations. What we are seeing is a lack of professionalism. A small group of any trade or profession are really not with it. Plumbers, doctors, lawyers and pilots. They just show up and collect their pay. I’ve have specific knowledge of pilots that just do the minimum, just squeek by at training, land half way down the runway or have to taxi a half mile to get the the taxiway after max reverse and max braking. They usually get by with minimum performance, but every once in a while they get in a situation where skill and training are necessary to complete the flight and we read the their story on the front page.

I always thought it was the art of flying not aoutomation ?

Automation dependency is a flight safety hazard and will get worse with the employment of inexperienced cadets into the second in command seat of jet transports and advanced turbo-props. Despite arguments that full use of automation is directed by airline managers, there are always ample opportunities to hand fly without flight directors in the climb and descent/approach phases. It boils down to laziness by captains. In turn this lassitude filters down to first officers who see their captains finding any feeble excuse to discourage the first officer from switching off the crutch of automatics and hand flying raw data. Hand flying with the flight director on is a waste of time since the design of the flight director requires full attention to the crossed needles rather than a full panel instrument scanning. Tunnel vision becomes inevitable.

Automation complacency is now acceptable to most airline pilots because they simply cannot be bothered to keep their hand in on manual raw data skills apart from a few minutes on a CAVOK approach down the ILS.

Moreover, until airlines and regulators insist that fifty percent of all simulator training including instrument ratings is flown on raw data hand flying, the current situation with loss of control in IMC as primary cause of accidents will continue. Don’t hold you breath on that policy ever being implemented, though though

Apparently its happened to another AirFrance A340 again see this: http://www.smh.com.au/travel/travel-incidents/probe-as-air-france-plane-suffers-new-autopilot-shutdown-20110907-1jwv9.html

Flying in the Inter-tropical zone has been written about by Ernest K. Gann in “Fate is the Hunter”.

Perhaps there something about supercritical wings flying in turbulence with autopilot that needs to be researched more thoroughly.

I don’t think Ernie ever flew a supercritical wing but I well remember him writing about flying in the intertropical convergence zone. Good stuff, Maybe I’ll go back and read it again.

That’s my point. When Gann and Bob Buck were flying DC4s and 707s they took a thrashing in the intertropical zone but managed it. Today’s airliners are flying at critical angle of attack for the given weight, speed, density etc. So when turbulence (windshear)at 35,000 ft happens, the supercritical applecart upsets too suddenly for even the autopilot to correct so the autopilot trips out (brainfreeze). Just my conjecture/hypothesis.

Shahryar,

Well, I’d argue that your conjecture is not correct.

A reasonable pilot will select an altitude with reasonable buffet protection so the AP will handle most turbulence without and issue.

If it gets really bad, then hand fly it. If there’s failures and issues like th AF flight, you do what’s necessary to fly the plane, which the pilots didn’t do and apparently were not trained to do.

And, you really don’t have windshear at 350…. different animal.

Over the time I flew the 47 to the far east and Austrailia for 8 years, I can’t recall one time where our crews had an issue with turb they couldn’t handle at 350. Some rough rides, but out of control… no.

Pete Garrison made a sage observation in his Flying column: Why was the A330 autopilot programmed to shut off when it lost airspeed indications instead of doing nothing? And if the plane was flying Ok before AP disconnect what compelled the crew to pitch up rather than continue doing nothing?

The there is the issue of the standby attitude indicator. The plane had one, just to the right of the pilot. One wonders why the airline pays to fly it around the world if nobody’s encouraged to use it?

Automation is just another tool we have available as pilots to allow us to successfully complete our mission with the highest level of safety and comfort.

The question is really when to use the automation and when not to as well as to fully understand the equipment’s normal functions and failure modes. The goal is to make flight safer in varying conditions.

In the part 91 world, proper training and use of automation is very important to reducing stress and fatigue in the single pilot cockpit during flight in IMC.

Hand flying during most phases of flight below the flight levels is certainly fun in VMC and is a great way to keep stick and rudder skills fresh. Practicing hand flying in true or simulated IMC is critical to maintain confidence if autopilot failure occurs in real IMC.

As a CFI, I encourage the development and continual practice of manual control of the aircraft but also teach the proper use and monitoring of the automation early in the process of transitioning pilots to any TAA’s.

Dealing with in flight failure of an autopilot is no different than teaching a primary student how to deal with an engine failure. Positive outcomes of all emergency situations require prompt detection of the problem, an accurate determination of the failure mode and timely action to remedy the problem.

The weak link is often the human in the cockpit even if we don’t want to admit it could be us on any given day. The best defense is clearly stated in a classic quote by Clint Eastwood. “A man’s got to know his limitations”. Or in flying world, “a pilot’s got to know his limitations and those of his ride”. Setting personal minimums appropriate to the pilot, aircraft environment and mission are critical.

<<>>

Gregg,

I’d argue that the failure of an autopilot is not an emergency, at least not in the planes I’ve flown. I can’t think of a plane that can’t be dispatched with the autopilot(s) inop. And it’s certainly not in the class of failure as an engine loss, especially if that’s your only engine.

Now, it’s sure prudent to recognize the autopilot failure and deal with it accordingly…. like “fly the plane”.

As an instructor, I have found that pilots, unless they have training to the contrary, tend to focus on those devices in the cockpit that they use all the time, or that were emphasized in training. In general aviation, the pilot who has success with the attitude indicator/flight director tends to ignore the turn coordinator (or turn and bank) when the attitude indicator/flight director begins to fail. Putting that into his instrument scan takes some adjustment. The same is true with the Standby Attitude. Failing the pilots attitude indicator to make him fly on the standby is a rare occurrence in most airline training operations.

In the air carrier world, the focus tends to go on to the displays with all their warnings. The Quantas A-380 where the engine exploded was a good example of prioritizing tasks and making sure that someone was competently flying the airplane. It was not at night or over the Atlantic, but they had a lot of other serious problems that they handled and were able to get the aircraft back on the ground safely with a minimum of fuss and bother.

The other advantage the Quantas crew had was a very qualified crew with a lot of extra very experienced help. That was not present on AF447. The crew of AF447 could have recovered from that situation if they had the training and skills. It is unfortunate that it takes the loss of the aircraft and passengers for anyone to take note of the problem.

Why the pilots did not just maintain power and attitude when everything started going bad is because they were probably never trained to do so. No one in the training department or the manufacturer wanted to cast negative aspersions on the automation installed in the aircraft. The attitude of those folks is that, ain’t gonna happen.

Concentrating on their displays which were going wild with warnings and problems was probalby where they were focused. The two pilots in the seats evidently thought that flying the airplane was not as important as the flashing displays, which they couldn’t do much about anyway.

Why they pulled the sidestick back and held it there makes no sense at all. Climbing the aircraft over 3,000 feet directly into a stall makes no sense what so ever!

As I said, I think it is a lack of training about what must happen when the automation quits for any reason and the development of skills that allow a pilot to fly and aircraft when the autopilot goes south.

There have been what were considered autopilot failure accidents in some high performance light aircraft that killed their pilots when they could not maintain control of the aircraft in cloud, without an operational autopilot. At least one that I remember ended up as a fatal accident.

This accident was the result of the “Fly the aircraft with the autopilot at all times” attitude of the manufacturers and airline managements. Pilots can’t be expected to know how to fly the aircraft without the autopilot if they are never allowed to practice.

Automation addiction is here to stay. The latest example just published in Japan is the incident involving a Boeing 737 which rolled almost inverted at night. The captain was absent from the cockpit and on his return from down the back asked the first officer to unlock the flight deck door. Apparently the first officer was none to bright because he actuated the electrically operated rudder trim knob (switch) instead of the cockpit door switch. The automatic pilot compensated for the rudder movement by applying aileron and spoilers and this eventually caused the autopilot to disengage. The first officer made things worse by not knowing how to level the wings manually and the result was the 737 became inverted through 130 degrees angle of bank and 40 degrees nose down. It was the first officers lack of flying skill in manual flying that caused the extreme unusual attitude – not the fact the first officer hit the wrong switch by mistake to open the cockpit door. There is no doubt that these sort of loss of control incidents will happen from time to time because of lack of handling skills by pilots of sophisticated jet transports who are brought up by airlines to use automation from shortly after rotation from the runway to short final approach on an ILS

Further to my comments on preceding message which discusses the unusual attitude that occured to a Japanese 737 recently, I think this extract from another professional pilot’s website is pertinent. The writer states:

“First of all, the vast majority of simulator type rating training and recurrent training is with full use of automatics. Thus, incompetence at manual flying would rarely show up unless an inadvertent unusual attitude just happened to occur. Apart from specific non-normals (manual reversion for example) hand flying is usually confined to the last part of an ILS and even that would be with FD and AT engaged.

Secondly, most unusual attitude training ( if practiced at all) is kept within the Boeing definition of unusual attitudes which are clearly stated in the FCTM. In fact, these are quite benign attitudes and easily recoverable. Rightly or wrongly, recovery in IMC from inverted nose down flight is rarely practiced in the simulator and it is left to the pilot to learn by reading from the FCTM and QRH sections rather than practicing in the simulator.

To have found himself in the extreme attitude described in the incident report, the copilot must have been way behind the aircraft to have allowed it to develop into such a serious Upset. In fact, it is most probable the copilot himself applied erroneous manual inputs to the flight controls that exacerbated the initial problem caused by inadvertent trim input.

With most simulator training confined to box ticking exercises designed to minimize training costs, it is no wonder that pilots are rarely given the opportunity to assiduously practice manual flight manoeuvres that require good skills such as Jet Upset and stall recoveries at high altitude as well as crosswind landings on slippery runways.

To make things more difficult for new pilots, it is rare to have a simulator instructor set a good example by personally demonstrating how to fly these manouvres, before handing over control to the student to have a go. The assumption seems to be that if the student has a commercial pilot’s licence there should be no need for an instructor to demonstrate. Not all students are aces and an instructor demonstration may be needed rather than a box quickly ticked”.

More hands on training is the correct approach, unless and until more capable autopilots are developed. No airspeed indication from Pitot tubes – autopilot should use GPS data; no GPS data – it should use inertial data from accelerometers and gyros and compass; it should use attitude, thrust lever position and engine RPM to estimate speed and direction. There are alternative ways to backup frozen Pitot tubes to keep the plane within flight envelope. Such backup data must be processed quickly, and a good automatic system will do it better than humans, because some complex computations will be involved. Today’s autopilots have to be much improved to get there. Until then more hands-on training is the way to go – humans will have to compensate for any shortcomings of the autopilot.

As one who has enjoyed both general aviation (48 years) and commercial aviation (airline flying for 32 years), I have to say that I would put my life in the hands of an airline pilot anytime before I would a GA pilot. There is more than just “stick and rudder” skills and the longer you fly (I still fly GA aircraft (taildraggers too)) the more you realize that experience and grey matter win out over the “top gun” pilot anytime.

I think this particular accident has more to do with the difficulties of interpreting the misleading data resulting from the clogged/frozen pitot tubes vs. not knowing how to recover from a stall which certainly at least the captain should have been able to do. I base this opinion on a similar crash that happened a few years back with a Turkish managed airline flight: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birgenair_Flight_301 .The Pitot tubes in this case were likely clogged by believe it or not mud wasps (the plane was a last minute substitute and had been sitting on the tarmac for weeks allowing the bugs to clogg up the tube). The accident occurred at night during climb out – while the crew was completely focused on the aircraft. The warnings issued as a result of the blocked pitot tube were wildly conflicting & nearly impossible to interpret. The airplane wound up stalled and inverted. The discrepanies in airspeed began during the takeoff roll. One could only imagine how difficult this situation was in the Airfrance scenario when it happened seemingly without warning during cruise. In the example above, the Turkish airline pilots had been focused on the problem right from he beginning and they weren’t able to resolve it successfully – imagine waking up from a rest as was the case with the Airfrance captain and being thrown into this. Point I’m trying to make here is that these guys probably did the best they could have done under the circumstances – what happened there was not likely the result of an incompetent crew or automation or not knowing about stalls – it was an enormously complicated and confusing situation in the sense that the clues in the form of warnings did not point directly to the source of the problem. I hope that the media will hold off passing judgement on the crew until all the facts are out. I suppose that more training should be given to deal with this specific scenario. But I would defer that to the capeable airline pilots on this thread as all my time is in SEL’s.

Several articles that I’ve read on this say that the frozen pitot tubes only lasted for one of the four minutes the airplane was out of control. Is this true? If so the pilots had reliable info for three minutes before splashdown and should have been able to recover. If it isn’t true then I’ll defer to the final investigation report before making a decision on the pilots abilities.

Actually, it would not have mattered. If they had recognized the situation they were in, they would have instituted the “Unreliable Airspeed Indication” checklist and flown the airplane by pitch and power. It works like a charm.

The latest recent incident graphically illustrates where automation addiction has taken the industry. An Air India Express captain lacked the skill to conduct a safe cross wind landing after two attempts. On the third attempt he decided the autopilot could do better and set up the 737 for an autoland in a 35 knot crosswind far above the crosswind limits for an autoland. The aircraft “arrived” and burst several tyres. The really frightening part however was the captain was so traumatised that he held his feet on the brakes and kept the engines running for 10 minutes until the rescue services persuaded him to close down the engines so they could tow away the 737 from the runway.

As an airline pilot, I was as fascinated by this accident as I was of the Colgan Air accident in Buffalo. It is hard to know what was going on in the pilots heads as they struggled to understand what their airplane was doing. I have an unconventional view of the Buffalo accident, believing that the Captain was applying tail plane stall due to icing procedures. It is not a perfect match, but it is the one that makes the most sense. NASA’s video on tail plane stalls was making the rounds in aviation circles at the time this accident happened. While he was totally unaware of his low airspeed, I can see how he interpreted the stick pusher as the pitch down caused by a tail plane stall. This happened shortly after the flaps were extended. This also conforms to what we know about tail plane stalls, they are worse if flaps are extended. The stall warning horn blaring in his ear should have clued him into what was really going on. The stall warning is a main wing phenomenon. A tail plane stall will not trigger a stall warning.

As for automation addiction, I counter with situational awareness. If you know where you are and what your airplane is doing, you should not be surprised when a failure occurs. However, some failure modes of modern avionics and flight management systems can be bizarre indeed. I think airline training facilities need to do more to train pilots in the modern art of interpreting avionic failure modes. You also never hear about the pilots who successfully negotiate a failure such as the one confronting the Air France pilots.

David Heberling has it right. As long as you have an operating attitude gyro and power indication, you should be able to fly the airplane. All the other indications can be wrong, and the autopilot can be off. Assume the right attitude and apply the proper power and the airplane will fly as expected. Anyone who does not understand this or cannot apply this principal is no pilot in my book. What are these guys doing in their sim sessions? Obviously not this. They should be practicing this.

By the way, I read nothing to indicate that there was a failure of any attitude instrument in the AF 447 crash, only the instruments that work off the frozen pitot tube were affected. That means altitude and airspeed, both of which can be inferred in large part by interpreting GPS information using GPS altitude and GPS groundspeed. The crew could have done this and/or fly by attitude and power HAD THEY BEEN MENTALLY PREPARED to do so. It does not take an ATP to learn these techniques. Most of the private pilots I know could easily do these things.

A contributing factor is the lack of feedback in the Airbus. The first officer has no idea what the pilot is doing with his sidestick and vice-versa. Move one sidestick, and the other does not move. So the pilot-flying was pulling up on the elevator control nearly the whole time they plunged and the other pilot(s) had no idea that this is what he was doing. The same thing applies to the autothrottles. When autothrottle adjusts the power, the throttle levers on the Airbus do not move, depriving the pilots of valuable feedback. Thus the autopilot can do its thing unbeknown to the pilots. Then there is the little item of stall warning being terminated by the computer if the airspeed gets below a certain value. Whose bright idea was that? How are the pilots supposed to rely on a stall warning that cuts in and out? Certainly this was a poor decision by Airbus, and should be corrected.

So it is not automation per se that is the problem, but the poor implementation of it, and the failure to train pilots fly the airplane when the automation fails.

In regard to the fly-by-wire system in the Airbus and the fact that the control sticks move independently of each other. There is a protocol we employ when flying in the Airbus. Since only one pilot can be in control of the airplane at a time, that pilot announces “My Aircraft”. When you hand off the airplane to the other pilot, you announce,”Your aircraft”. If the other pilot is screwing up, you can take control by holding down the autopilot disconnect button on your side stick. This locks out the other pilot’s side stick. You had better announce your take over and why you are doing it or else a “take over” war could develop.

Also, we do not train for failure modes of the automation. I believe that the current thinking is if the automation fails, you devolve to basic flying skills and build from there. It is too difficult to know what to trust as the failure unfolds. So it is far better to go straight to pitch and power to keep the airplane flying and then take the time to figure things out. Really, all the AF crew had to do was keep the power where it was before the failure, and keep the attitude where it was before the failure.

As for the autothrottles, I have heard so much drivel about the fact that they do not move. I believe that is why there are such things as engine instruments. You learn very quickly to include them in your scan. This includes while you are flying on autopilot. People are fond of saying that the airbus has no feedback through the flight controls. I say hogwash. I hand fly the ‘bus quite a bit. I can tell when it is heavy or when it is light. I can also feel the difference between on speed and when it is slow (on approach or initial take off). There is also a “sweet spot” during landing when the wheels are just above the runway. It is hard to describe, but it can definitely be felt. It can be elusive sometimes, but you know when you are “in the groove”.

This is a genuine problem that has been brewing for sometime, and it has surfaced! The Airbus builds an airliner that is based on pilots of a lessor skill and flying ability flying it, so they build in more automation to compensate for that. The result, you can not over ride the controls/the computer on ‘le Bus’. The on-board computer system has the final word. What has happened to the pilot? He/she is engineered out of the picture. Boeing has not done this, yet. It will likely get worse before it gets better. Piloting skills are deteriorating with increasing automation. Nothing new here, but a scary prospect. Are we doing anything to address this? I am not aware of it. Manufacturers are selling/pushing technology and automation, and don’t seem to be concerned with piloting skills. Again, nothing new here.

John,

I disagree about pilot skills deteriorating. Today, we have better training, more of it, and more information. And the safety record is improving.

The dependency on the autopilot has been around for years, not new.

The dependency on the newer automation can be an issue, if not properly trained for or mismanaged.

As for the Bus, I’m not a fan of it, and prefer Boeing. And, yes, I believe the design to take the pilot out of control is a mistake, however, with proper training and an understanding of how it works, it can get the job done (usually safely) ….

What can we do about it? Well, for our GA flying we need to take an aggressive role on training and currency. And when we get new equipment, we need training on it and learn how to manage it. As for the airline pilots here, most don’t have a lot of control over training, unless they work at the training center, but it’s improved dramatically over the years (well, at least the US carriers).

So, pay attention in class….

Larryo,

Well, we may just disagree. I completely disagree with your comments re better pilot training. Let me ask you, where do we have better pilot training? I work in the training business, but on a professional level. The pilots I work with are professional, and are generally proficient, having to take a check-ride every 6 months to keep their job. However, at different levels of pilot training, pilot skills are an issue.

I have had clients tell me of new hires at a regional airline who had poor piloting skills, and yet were allowed to ‘pass’ the training because the airline ‘needed the bodies’ in the right seat. Just 2 nights ago, at a FAASTeam Rep meeting, an FAA Inspector who was present and who addressed us, was ‘appalled’ at the quality of the CFI applicants whom he was seeing, citing not well prepared. Many were issued pink slips. He is questioning the competence of their recommending instructor.

Please tell me, where do you see pilot skills not deteriorating? Increased automation is resulting in pilots relying more on automation, less on hands-on flying, correct? How many pilots are competent/proficient in cross wind landings, for example? Just one example.

I look forward to your reply.

Thank you.

I can tell you where we are going with automation. The big push is on in the flying freight world to move to single pilot ops. That will eventually move to the people movers too. Someday in the future, there will be no pilots on the flight deck. My crystal ball does work well enough to say when that will happen. To say “NEVER” would be a big mistake. History is full of people who said, “NEVER” against the march of technology and were left behind.

How many pilots are competent/proficient in cross wind landings, for example? Just one example.

I recently asked an experienced first officer with 3000 hours on 737’s in Asia to demonstrate a 35 knot crosswind landing in the simulator. He initially objected even though he had a command type rating. He was physically frightened even though it was just a simulator. In short he didn’t have a clue with control movements. He hit the runway with full drift still applied and no flare. The simulator recorded a crash. This was repeated three times and it was clear he was out of his depth. Asked why he had not removed drift before touch-down he said he had never landed above 15 knots in the real aircraft and that all the captains he flew with never removed drift. The standard of manual flying in some operators in the Asian region is very sub-standard and this is mainly due to total reliance on the automatics.

Having frequently observed experienced captains in the simulator attempting to fly a raw data ILS in nil wind and weaving through the localiser and up and down through the glide slope made me realize how much automation dependency is rife in many operators. Often this is sheer laziness but it doesn’t help when management bulletins urge full use of automatics even in clear weather. It is never ending.

John,

We need to get you into a better airline …..

While we sure see a few airline pilots that could used some retraining, the majority do pretty well and would not have a problem with your 35kt cross wind.

There’s no doubt in my mind that I could get a 737 down in that, but have ~6K hours in them and find them a very forgiving and flexible plane. However, it wouldn’t be pretty and would take that as a last resort.

As for airline pilots using automation “all the time”… I didnt see it at my airline. Rarely would one autoland, and often would shoot their approaches by hand (if appropriate).

Enroute, I think the AP is appropriate, as is for some approaches, descents, etc, but works to shut it off occasionally and just hand fly , straight and level. I don’t see a lot of “over dependence” in the autopilot. What I do see occasionally, is a bit of confusion and too much attention to the glass, and programming the FMS, or GPS when we should be looking out.

The A330 accident was not a function of too much use of the auto pilot. It was becasue the pilots in the cockpit were not able to understand what there instruments were telling them, in particular the attitude indicator.

Back in the 60’s, I was an autopilot/compass systems technician in the USAF. Pilots tried to get out of flying in inclement weather by writing up the autopilot. Didn’t work. Strategic Air Command told the pilots if they didn’t want to fly, turn in their wings, they were no longer pilots. The autopilot was there to ASSIST them, not do their job. The modern autopilot is a vary valuable tool, but is too often relied on to replace good piloting.

I have flown a LOT of Glass Cockpits and taught the Glass 737-300/500. There was a Line Check Airman I had on my first IOE as a First Officer. He made me hand fly the first leg of 2 hours. Then gave me my choice of one piece of automation, each leg thereafter. I would follow that pattern, conditions permitting the rest of my career. Had I been allowed to become Flight Director Dependent or Automation Dependent, I know I would not have had the degree of confidence in the jet I flew or myself as a Pilot. It was a great lesson. I also flew the Airbus and NEVER quite felt the same in that plane as in the Boeing jets. That’s just me!