If anything, general aviation has been in a deeper slump than the general economy since the Dow average bounced off a 6,469 bottom on March 6, 2009. The Dow has been back up around 15,000 but general aviation has yet to bounce back in similar fashion.

The question I have relates to serious accident activity in general aviation. We all know that the accident rate does not vary by much so the number of fatal accidents tells us a lot about flying activity. What has happened here during the economic collapse and rebound and the general aviation collapse without a rebound?

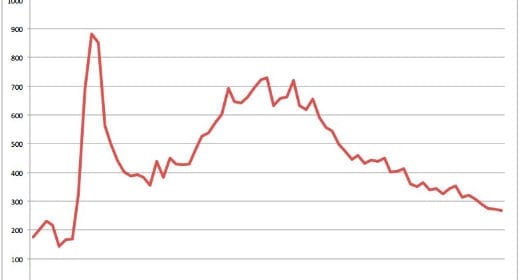

For the record, there were 882 fatal accidents in 1947, the highest yearly total ever. Activity was at a peak because of GI-Bill flight training and the accident rate was higher than it is today.

The activity collapsed when the GI-Bill training ended. There were 441 fatal accidents in 1951. That year held the record of the lowest level of activity until GA got into its recent extended slump.

Things were humming again by 1976 which saw 729 fatal accidents. The number started down and was below 500 by 1985, which was the start of the painfully long contraction in general aviation activity. Now it is bumping along with numbers like 267.

There is no quick sign of any specific reaction to the economic bust that resulted in that 2009 low on the Dow but most observers do feel like flying activity dropped off and remains lower now. If that is true, why do we have the same number of fatal accidents?

I am sure there are many ideas on this and to satisfy my curiosity I read all the fatal accident reports issued by the NTSB for 2009. I came away from that eye- and mind-numbing exercise with my own thoughts and ideas which I will share. If anyone wants to look at this from a different perspective, the NTSB web site awaits. (FYI, the NTSB identified airplanes by type and I might have counted a few light sport airplanes as experimental simply because I don’t know all the light sport names.)

It appears to me that the economic malaise has changed some of the basic nature of our flying activity.

Looking at the 48 contiguous states and fixed-wing powered airplanes other than those used in agricultural flying covers what most pilots are doing.

I read 224 such reports. If any one thing stood out it is the fact that 82 of those covered what I perceived to be experimental airplanes. That would be about 36-percent of the accidents in airplanes that fly about ten-percent of the hours according to government numbers.

The accident numbers are pretty well established but the hour numbers have always been wild guesses. Simply put, the FAA doesn’t have a real clue about what we do with our airplanes or how much we use them. I think the 2009 record tells us that experimental airplanes flew a lot more that year regardless of what the FAA says about hours flown.

Experimental airplanes accounted for more crashes in 2009 than usual – is that because they had a bad year or were they flying more?

For 2010, experimental airplanes showed significant improvement in the number of accidents and I think the 2009 picture might reflect the fact that pilots of store-bought airplanes took a bigger IRA hit in the bear market than did pilots of experimental airplanes who just kept on flyin’. Or perhaps it is because pilots who fly experimental airplanes just don’t worry as much about the balance in the old IRA.

A drop in the number of accidents in airplanes most often used for travel (over 140 knots cruise) along with less IFR in IMC and night accidents also suggests a reduced level of purposeful cross-country flying. To look a bit more than this, I examined the record of two airplanes that tend to be out there flying IFR in IMC, the Beechcraft Baron and Cessna 210. In both cases there were twice as many fatal accidents in 2004 as in 2009. I doubt if all airplanes would show a similar pattern but that one is there and the flying activity in those airplanes is probably down sharply.

Power problems leading to accidents appear to be a somewhat larger part of the 2009 accident picture than in prior years. Twenty-two percent of the experimental airplanes were in fatal accidents that were preceded by a partial or total power loss. The number was 18-percent for store-bought airplanes. (Fuel exhaustion, the ultimate power problem, is included in both cases.)

The relatively small difference there is interesting because fuel and air induction system design and construction is a big cause of power losses in experimental airplanes. That is not the case with the others.

I would think there is a possibility that some engine maintenance might be deferred in times of economic stress, especially in airplanes with more complex engines that require a lot of expensive care to keep running strong and reliably.

There were twice as many structural failures in experimental airplanes which is significant because there are so many fewer of them. These tend not to happen in the experimental airplanes that come from well-established kit manufacturers.

The NTSB has done something interesting, or strange, in reporting on pilot incapacitation or impairment. More often than not, they mention medications or drugs found in the pilot’s blood but then claim there is not enough evidence to say how this might have affected the pilot’s performance. Thus it is not mentioned in the probable cause. That seems to be different from the way it has been done. The total for possible impairment/incapacitation is up a bit at 28. That is over ten-percent which makes it a point to ponder.

The NTSB does include alcohol in the probable cause any time the pilots is over the regulatory limit for flying which is half or less than the regulation for driving, in most cases. There seem to be fewer alcohol-related accidents than in the past. The same is true in automobiles so finally the public is getting the message.

I counted four midair collisions which is a smaller number than usual. In context, though, this means that eight airplanes were involved in midair collisions.

This informal look at a year’s worth of accidents suggests a few things.

In times of economic malaise, the more expensive forms of flying appear to slow down more than the less expensive.

All the types of accidents we have seen over the years are still there, even in the areas where there is diminished activity.

This has been true for a long time, but with losses of control, including stall/spin events, a number one cause, then a greater emphasis on basic flying skill is the best way to bring about needed improvement in general aviation safety.

- From the archives: how valuable are check rides? - July 30, 2019

- From the archives: the 1968 Reading Show - July 2, 2019

- From the archives: Richard Collins goes behind the scenes at Center - June 4, 2019

My field observations seem to agree somewhat with this study:

1) Homebuilts (mostly kitplanes), particularily Van’s Aircraft, are making up a larger percentage of the flying than in the past. Thus, more exposure.

2) The traveling airplanes, like the Baron and the C210, are doing less traveling due to cost and safety concerns versus cheap airline travel with virtually no safety concerns.

I think the NTSB and the FAA should back off trying to make the homebuilt accident rate equal to the certified rate. That’s why the “Experimental” and “Passenger Warning” placards are required on these planes; to warn that they may not be as safe. Same as we don’t expect librarians to have the same fatal rate as rock climbers.

Will more training in basic piloting skills help? Seems unlikely since in the worst year shown, 1947, the emphasis in training was on basic skills; much more so than later training ciriculums. Replacing the old airplanes with new ones that won’t stall might help; whether by electronic stick pushers or inherent aero design. Also it would help to have new planes that are not susceptible to carb ice and fuel systems that do not require pilot management to get all of the available fuel to the engine (same as required of turbine aircraft).

There was an article about 15 years ago (can’t remember where i read it or who wrote it, I wish I would have saved it) where the researchers sifted through dozens of earlier traffic accident studies to see if they could make some positive correlation to automobile fatalities. Speed limits, age limits, training, road conditions, technology, driver age and many other factors all had some influence but were not sound indicators statistically. There was only one which could be consistently correlated: fuel prices. If gas is expensive, we drive less, and crash our cars less.

Richard,

Thank you for the thought provoking analysis!

It would seem like 09 might be too close to ground zero. Many folks didn’t really get impacted until their company ran out of Schlitz(sp) later that year – my anecdotal thoughts only.

If that’s the case it would be interesting to see how 2010 compared to 2009.

I think there’s no question that flying down, but could that in itself cause our fatal rates to incrementally increase? Less flying is less exoposure, but it also means less proficiency, which can easily move our rates the wrong way.

My 2 cents.

Brent over at iFLYblog.com