|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I did both private and instrument training over the last few years out of Palo Alto (PAO). Since then, I relocated from San Francisco to Seattle and have not yet found a flight school or club to use in the Seattle area, so my logbook has been quite neglected this summer. When I came back to the Bay Area for my college reunion, I found I had an afternoon to kill on the day I arrived, and decided to take advantage of it with my CFI and old club.

As the Delta flight from Seattle was landing, I was a bit confused because the sequence of turns wasn’t the normal one, and I was surprised when the 737 broke out at about 3000 feet, not over the Dumbarton Bridge as usual, but over Oakland. It turned out it was one of the rare occasions when they were landing to the south (landing 19, departing 10) instead of west (landing 28, departing 01). I didn’t realize it at the time, but this was first omen that the day might be a bit interesting!

I drove straight from landing at SFO to PAO to meet Bobby and get started. I was lucky to get him—the day after this he was headed to United’s training facility in Colorado to get his 757/767 type rating, after working the last few years at Alaska on the A320. The goal was to do a mini-BFR, as I hadn’t really flown since getting my seaplane rating in Alaska in May, plus six approaches and a hold to get IFR currency back. We first did an hour in the simulator to get three of the approaches in for free (the club gives you one hour per month, per simulator each month gratis), and then started to look at real-world weather.

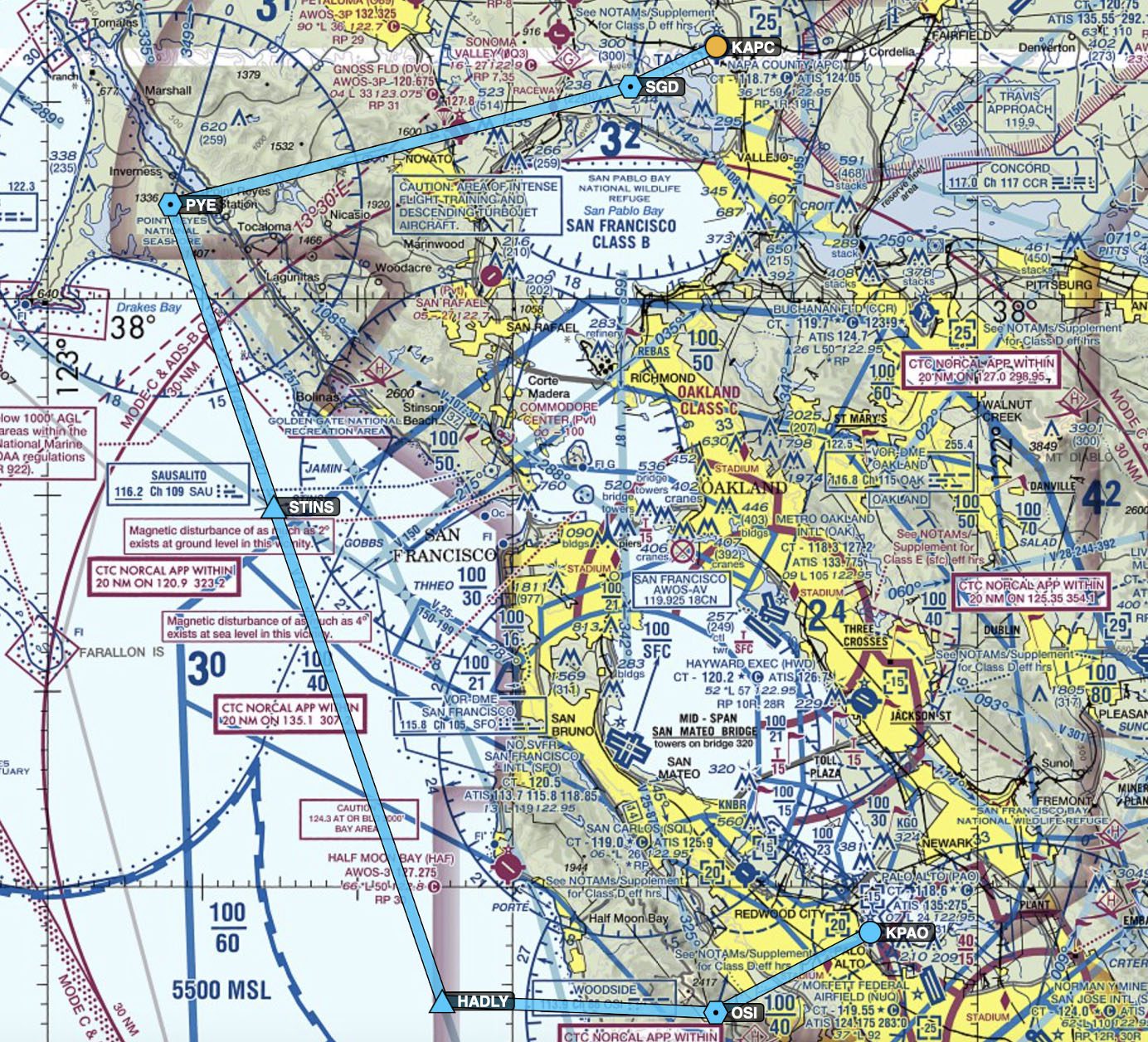

It was a perfect day for IFR flying: the freezing level was higher than 12,000 (not going to get a 172 up there), and the atmosphere was stable, with everything socked in by lots of rainy stratocumulus. We decided to set out for Santa Rosa, as North Bay had the lowest ceilings. Filing IFR in and out of the Bay Area is often an exercise in gratuitously circuitous routing, so it wasn’t a surprise when the clearance came back as this:

When I mapped the cleared route, I assumed it likely we’d get a big shortcut from SUNOL to CCR, but we ended up flying the entire thing save for cutting the corner at OAKEY by a few miles. On this routing you get to talk to three different Norcal Approach sectors, Travis Approach (military controllers with a very distinct style from FAA controllers), and then two Oakland Center sectors (plus towers on either end).

We entered IMC at about 4000 ft. halfway to SUNOL and then broke out while cruising at 6000 around SGD. There was one hiccup on the approach clearance: were told expect RNAV 32, then the controllers changed and we got the approach clearance as ILS 32; I read it back halfway before saying, “wait, did you say ILS?” He quickly reissued as RNAV. On the LPV approach we got under one layer at about 1500 but there was lots of scud over the airport, so we ended up having only the approach lights—a bright, beautiful MALSR. It’s quite the sight when all you have are kilowatts of lighting ripping through the fog. The approach wasn’t quite all the way to 200 ft. but it was one of only a handful I’d done (thus far) to near-minimums and which was questionable to the last minute. Turns out I still remembered how to land and I put it down right on the 1000 ft. markers.

Bobby taxied us towards the departure queue while I filed to Napa. Interestingly, we got one expected route back from ForeFlight right away and then a modified one about five seconds before the controller called us with our clearance. I assume the center controller must have manually reworked the clearance before releasing it for delivery, and the computers managed to deliver it at the same time the local tower guy got it. This pattern happened at the next airport too.

We were #4 for the runway but airborne in a reasonable amount of time. This route too was not exactly direct and characterized humorously by both delay vectors way out of the way and the controller asking us to keep our speed up (in a Skyhawk! Pointed directly into a 25-30 knot headwind!).

We shot a not particularly difficult ILS to Napa, breaking out at 1000 ft. or so and landing a bit after 5:30, giving us time to file and get airborne back to Palo Alto to arrive before night. We got the clearance quickly, but release was not forthcoming. Tower confessed that center wasn’t even taking his calls (the clearance came either via a separate flight data position in ATC or printed out directly in the tower, whereas the actual sector controller approves release). We spent more than a half hour at the runway threshold—there goes $160 right there.

I tuned in the center frequency while we waited, and he was busy giving SFO and OAK arrivals from the north holds over the PYE VOR. This is very rare these days in the airline world, because ATC software precisely metes out runway departure times (to the minute) so that there is no congestion on arrival. A Caravan trying to fly Santa Rosa to Oakland was given a 45-minute airborne hold while we listened.

This leg was to be another out of the way route, flying the Point Reyes 3 arrival. In the days before RNAV STARs, this would have been the route taken for any SFO arrival from the north. Having been issued it in the past, I had filed for 8,000 knowing this assures engine-out glide to land in a no-wind environment (of which there was 20-25 knots blowing us onshore to boot). Center let us know, unfortunately, that 5000 was all we were going to get today because jets entering downwind for SFO’s runway 19 would be at 6-8000 ft.

On the bright side, this leg would be more forthcoming with shortcuts. After a few vectors to get out of the way of straight-in arrivals to Oakland, we got direct STINS from center, and as soon as the handoff to Norcal came, we got direct OSI which kept us over land the whole way. This was a grueling leg, with 90-95 knot groundspeeds despite running full “rental power” and 130-135 knot true airspeed. Plus, other jet arrivals were indeed just 1,000 feet above us.

We got two traffic calls from ATC, one a 777 passing 1,000 feet directly overhead, and another a 737 that was 1000 feet above and about a minute ahead of us (in the perfect location to lay wake turbulence in our path). On the first call we could hear the warning alert in the background of the controller’s radio, and it was a bit out of a Tom Clancy movie watching the traffic blip on the map getting closer, turning yellow, red, and finally receding; a submarine evading a torpedo.

As we approached OSI, the Woodside VOR, we got a bit of bad news: the departure delay and slow progress meant that legal “night” was impending and the Palo Alto instrument approach is not authorized at night. What were our intentions? The San Carlos approach is legal at night, and if we could break out before passing abeam Palo Alto, we could cancel and go there VFR.

The controller approved that plan, with a stern admonishment that we must confirm cancelling IFR before leaving the approach path (clearly, they’ve seen this scenario before). A few minutes later he relayed a report from a helicopter on our arrival path that clouds were down to 800 feet, which would totally spoil our plans.

Passing Woodside, we were given a heading to continue southeast, eventually with advice that we could expect to go 15-20 miles further before being turned inbound. The controller hinted at his true intentions when he said, “speed your discretion.” This was really a “linear hold,” as we would be on the same route and altitude as jets inbound to San Jose for a bit and controllers further south needed to create a gap we could fit in. When I figured out the hint, we pulled power way back, and with a 25-knot headwind we were only doing 60-65 knots over the ground.

It was at this point we realized this was going to be a real approach, not just for training. We were simultaneously contemplating three potential scenarios: an approach to San Carlos, broken off VFR for Palo Ato, a circling approach all the way into San Carlos, and a missed approach with need for a subsequent plan (circling minimums were 1260; the PIREP had some ceilings down to 800).

It was great to have someone who did this type of challenge every day (in the airlines, with commensurate training) in the other seat, as we were very effective at splitting tasks—me reviewing and briefing the approaches and decision criteria, him programming the avionics and then cross checking each other’s work. On top of this, we were watching the fuel gauges trickle below 10 gallons per tank. That was still nearly 2.5 hours of endurance (plenty to make it clear to Sacramento and shoot an approach there), but with how the G1000 draws the yellow region on the gauge, it was certainly a psychological factor.

Finally, the controller gave us our base turn. Here we go! Except no, it was too early, and he turned us outbound a bit longer. The real turn came, and a bit longer, direct AMEBY, where we would join the published approach. The throttle went from nearly coasting to full power and turning with the wind meant our groundspeed shot up from 70kts to almost 150kts. We were cleared to descend from 5,000 to 4,000 until the approach, and we dialed in the autopilot to a 1,300 fpm descent so that we could see how low the clouds went as soon as possible. We broke out just over the Apple campus at 4,000 and started to get our bearings.

There wasn’t a lot of low-lying scud here, which made us confident we’d be successful getting into Palo Alto. Bobby’s job would be to spot the airport out the front right side of the airplane and we would call to break off for PAO when he decided it was solidly achievable. I would fly the approach assuming we were landing San Carlos until then.

As we approached, we thought it was likely we had the airport beacon in sight, but unfortunately the green lens has faded, and it looked more like a flashing white light than a white-green alternating beacon. We made a slight left turn to join the approach at AMEBY, which then let us do another steep descent (slang for this style of approach is called “dive and drive”) to 2,000 feet, which made it quite easy to positively identify the airport. I called ATC to verify the official weather still made it legal to operate VFR (if Palo Alto had updated its weather report to 800 ft., it would no longer be legal to do this VFR maneuver). With that confirmation, I gave a jubilant “cancel IFR” call to the controller, who confirmed it. I waited a bit longer so he could update our information and not trigger altitude/conflict alerts on his scope and then turned to join the Palo Alto traffic pattern.

Cognizant that we were essentially flying a circling maneuver, after dark, to a procedure that didn’t authorize it, on the side of the runway that wasn’t authorized even when it was daytime, I stayed quite high (way above PAO circling minimums) and on a tight base pattern until I knew we were well inside all the obstacles north of the airport, before slipping down to join the VASI glidepath on short final. We touched down on the shortest runway of the day (some 2,300 feet vs the 7-8000 foo. runways at STS and APC) and coasted with light braking on the slippery surface to the turnoff at the far end of the runway. We were home!

When I reflect on this afternoon, two lessons come to mind. One invokes that adage about the three useless things in aviation, particularly fuel left on the ground. While we had plenty to safely execute the whole day’s mission, even had we needed an unplanned diversion to 50 nm or more away, there is no reason we couldn’t have started the afternoon with full tanks, adding ten gallons or so to our resources and ensuring fuel status need not be a factor on our minds during a busy and critical phase of flight.

Another is that we didn’t fully consider the cascading effects of long routings, slow groundspeeds, and release delays. Impending sunset was a threat we should have more fully briefed (and we had plenty of time) before departing for Palo Alto. We might have been more alert to San Carlos weather, other PIREPs, and been able to thoroughly consider more alternatives, such as a contact approach to Palo Alto.

All-in I logged six hours of instruction, four hours of Hobbs time, three takeoffs and landings, three hours of actual IMC, two approaches in the airplane (this last one wasn’t even log-able!), plus three more in the sim. ForeFlight shows nice green checkmarks next to currency items for the near future. And it was some of the most interesting, challenging, “real” technical flying I’ve done—stimulating in exactly the ways I thought it would be when I wanted to get the instrument rating.

- An IFR currency adventure - December 20, 2021

Thanks for this account, loaded as it is with great descriptions of the real-world complications that come with flying IFR in busy airspace.

Great account of getting a lot of training into a small amount of time. It sounds pretty exhausting and would be very difficult if you were doing it as a single pilot. I could envision the little pesky skyhawk flying in such busy airspace in marginal conditions and the controllers trying to figure out how to get you in or how to discourage you from completing your mission! I love the linear hold! ha ha Sounds like you are your friend make a great team. Thanks for sharing the experience and the reminder to take a few minutes to get the extra fuel just in case. Nothing worse than the stress of staring at a fuel gauge that is only accurate when the engine quits.

Nice work, John. Thank you for sharing your flight with us.

I used to commute to PAO every day from Cameron Park (O61), rain or shine, day or night. There is another “approach” to PAO which will get you in when no other approach can. My normal “approach” to PAO was as follows:

1. File for the Hayward and request LOC/DME 28L approach.

2. When handed off to tower, let them know you are really going to PAO and ask to have a special VFR ready for you.

3. If you break out at or before the MDA (likely), cancel IFR and get your special VFR, which almost always consists of, “Left turn direct to the San Mateo Bridge Toll Plaza.”

4. Turn left and go to the San Meteo Bridge Toll Plaza. When you get there Hayward tower will tell you to contact Palo Alto tower.

5. Turn left to follow the the E shoreline of the Bay. Contact PAO tower and tell them you are inbound from HWD along the E Bay shoreline and you would like a special VFR. They will tell you to report KGO radio station.

6. Follow the shoreline to KGO radio station. Do not run into the antennas, which you won’t if you are at 400’MSL or above.

7. Call PAO tower and report KGO, they will then give you your special VFR into their airspace.

8. Hop over KGO and cross the Dumbarton Bridge (we used to call it the Dumbo-tron) to the railroad trestle that parallels the Dumbo-tron on the south side.

9. Turn 45˚ right to parallel the railroad trestle and follow the railroad tracks. You are now on left base for runway 13. If the winds are more than 5kts then turn right downwind for 31.

I used to regularly execute this approach to PAO with 500′ ceilings and 1.5mi vis. Since I was inbound to HWD via ALTAM and SUNOL, I was out of the flow for SJC, OAK, and SFO. I almost never encountered a delay. No, this is not an approach for neophytes but it is a valid and safe approach for pilots who regularly operate out of PAO. It does point out the value of local knowledge and familiarity. It also points out that, sometimes, the best (and lowest minimums) instrument approach is VFR.

Sweet re-cap, John. Thanks for sharing it. I learned to fly at SQL and started my instrument training down there. I’ve done most of my flying around the SF Bay, probably like you. We recently moved up to Santa Rosa, so I’m now right next to STS and need to pick back up on finishing my IFR rating. I enjoyed following along on you training summary – all familiar areas. Thanks.

Interesting how someone so non-current was so on top of his game. I was never that sharp.

“… I found I had an afternoon to kill …”

Well, there’s my problem. “Free time” is an evasive lover.”

Great story John! Filled with nostalgia for all of us former PAO and Bay Area pilots :-)

I didn’t realize no IFR approaches are allowed into PAO after dark!?

That original APC-PAO routing would have been a no-go for me, way too far out over the ice cold ocean! Maybe that’s why I always did IFR practice inland.