I know that some readers don’t like for us to write about general aviation accidents and safety. That is too bad because the best flying lessons are found in accident reports where we learn about the all-important things that we should not do in airplanes.

By my count there were 121 certified fixed-wing airplanes (excluding agricultural) in fatal accidents in the 48 contiguous states in 2013. There were 40 in experimental airplanes. Looking back at 2006, before the wheels came off most everything, there were more: 192 certified and 66 experimental. Does that mean flying has gotten that much safer? No. All it means is that GA pilots are flying that much less. The fatal accident rate per 100,000 hours has not changed much, if at all, in recent years.

For this discussion, I read all the 2013 accident reports. True, 2014 would have been more current but too many NTSB reports from that year are still preliminary. I think 2013 well represents what is going on now. It is also true that I could have done this with computer runs but I find I get a more accurate feel for what is actually going on by reading the reports. I have been doing this since 1958.

In doing safety studies, I have always concentrated on fixed-wing airplanes in the 48 contiguous states with agricultural flying not considered. That covers what most of us do.

Is anything changing? Yes, some things are and others are staying the same. Perhaps the biggest change is the dramatic drop in flying activity that has led to fewer accidents.

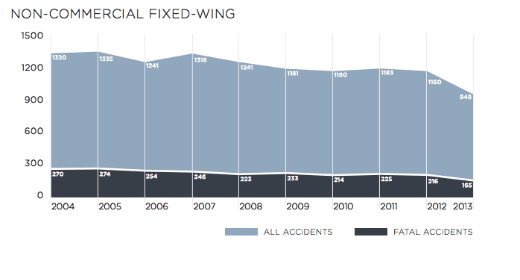

Fatal accidents have fallen, but mostly in lockstep with hours flown. (Courtesy AOPA Air Safety Institute)

The fatal accident rate has been pretty stable in recent years at just over one per 100,000 flying hours. It moves a little but probably always stays within the margin of error on the estimated flight hours (by the FAA) which is little more than a wild guess.

Nobody will argue that this rate is acceptable. It is not, it is terrible, but it is what we get from our pilot population and the only way to change it would be to alter the behavior of pilots and that’s not going to happen. It would take Draconian legislation to improve the accident rate and that would effectively eliminate GA as we know it.

The definition of non-fatal accidents is so broad that many events the public and even pilots might think of as an accident don’t make it to the NTSB list because they don’t meet the parameters. Fatal accidents are absolutes and are also what we most want to avoid.

Over the years I have lost over 50 people I know, some well, in airplane accidents. When I study the subject, I like to think I am looking for something I might have said to them before they took off on their last flight. Forget about improving the accident rate because all that is really possible is to help individual pilots learn to avoid the things that establish that accident rate.

Starting at the beginning, before and during the first minutes of flight, the accident records make strong suggestions

First might be fitness to fly. That is an individual decision, made on the ground, and where the NTSB mentions pilot ailments and over-the-counter and prescription drugs in narrative discussions, word on this doesn’t always make it to the probable cause statement presumably because the NTSB didn’t think it was part of the probable cause.

Some of the stuff pilots take before flying is pretty scary and in reading the accident reports I often feel that the drug might have had a substantial impact on the pilot’s performance even if the NTSB didn’t think so.

I found 16 accidents in 2013 that were or could have been related to legal drugs. That covered about ten-percent of the total fatal accidents in fixed-wing airplanes so it is definitely a factor.

As in years past, impairment caused by either alcohol or illegal drugs is a factor in some accidents but there is no trend in either direction on this.

Once a pilot decides he is fit to fly, next comes the plan for flying. If anything, the trend here suggests that more pilots are taking off before they are fully prepared to do so. Perhaps that is because airplanes are becoming more complex.

A loss of control soon after takeoff shows up in ten-percent of the fatal accidents. Not much time is spent in the first few minutes of flight so that is a proportionately large number. These were split about evenly between VFR and IFR departures.

With high-tech the rage, I just naturally looked for something I thought might be there: a pilot’s lack of familiarity with the avionics system. Sure enough, the NTSB listed that in the probable cause of a 2013 King Air 200 accident. The pilot was experienced in the type but was flying an airplane with an avionics system that he had not used before. He stalled the airplane at 400 feet on the departure and the NTSB thought that a lack of familiarity the avionics had something to do with this.

Having all those whistles and bells in the cockpit is wonderful, but if you don’t know how to blow the whistles and ring the bells, distractions caused by that stuff can kill you quick.

There’s an interesting thing about the 2013 losses of control soon after takeoff in instrument meteorological conditions: five of the seven airplanes involved were turbine-powered. Four of these were singles. Is this an aberration or a new trend?

Accidents like this used to be the province of single-engine retractables and light twins. These airplanes are far less active now and some of the pilots who used to fly them are flying turbines today, if they can afford to do so. So I think this a matter of the same type pilots flying different airplanes.

Question to self: “Am I sure I have all the ducks in a row for this departure?”

When considering certified airplanes only, engine failures and power problems loom large as an increasing area of risk. Close to 20-percent of the 2013 fatal accidents fall in this category. Almost half of those were multiengine airplanes. It has always been true that your chances of being done in are greater in a multiengine airplane after an engine failure than they are after the engine fails in a single. The flat-earth folks will give you many reasons why that shouldn’t really count but the facts are the facts.

What has changed is that half the twins with power problems were turbines. That is something new and might be attributed to the turbines flying relatively more hours as time passes. It is true that turbines have far less catastrophic failures than pistons but a lot of other things, including incorrect pilot actions, can interfere with the power output of turbine engines.

As always, stall/spin accidents are number one on the list, accounting for about 25-percent of the total fatal accidents. I’ll talk more about weather accidents in a minute, but here I want to say that they do have something in common with stall/spin accidents: both are usually fatal. Sure, people have survived both accident types but they are in a minority. In fact, a higher percentage of the occupants in midair collisions survive than do stall/spin and weather accident participants.

There is something new in the stall/spin reporting in 2013. Where the NTSB used to often say that the pilot failed to maintain airspeed, angle of attack is creeping into the discussion as they mention the failure to manage angle of attack as a cause.

It’s almost as if someone had an “aha” moment about angle of attack. News flash: knowledge of its importance has been around since the Wrights’ first flying, instrumentation has been available for years (I had AOA instrumentation in my Pacer 60 years ago), and in fact, most airplanes flying have an angle of attack warning system. It has always been called a stall warning but what it tells you is that the angle of attack is nearing that which results in a stall. It warns you of that regardless of the indicated airspeed, as in an accelerated stall.

Maybe if the stall warning were renamed the AOA warning perhaps the near-hysteria among government folks and some safety mavens about AOA would go away.

When my father started AIR FACTS in 1938, stall/spin accidents were the safety subject of the day. They still are and that will likely remain true for a long time. The accidents of today bear a great similarity to the ones of 77 years ago and I honestly can’t read the accident reports and identify many, if any, accidents that more complete AOA instrumentation would have prevented. If a pilot can’t get the message from the airspeed, from feel of the airplane, from the look of what is going on, and from the bleat of a stall horn, how can another gauge on the instrument panel help?

If there is a standard stall/spin event in more or less normal operations, it comes out of a steep turn at low altitude. Unless a pilot is cutting up, the most likely place for that to occur is on the turn from base to final in a badly botched approach. When you look at such accidents, the angle of bank in those fatal turns is usually far in excess of 30-degrees, which is the guideline for maximum bank angle at lower altitudes. You can bet that a pilot who is really bending it around in a steep turn to final is not looking at the instrument panel.

If the weather accidents that occur in visual and instrument conditions are combined, then in 2013 they actually outnumbered stall/spin. That would make weather the number one bad thing but weather accidents have always been separated into those that occur on VFR flights and those that occur on IFR flights. As has been true for a while, they are about evenly divided though the trend has been toward more IFR and fewer VFR weather accidents.

Years ago, when most weather accidents were VFR, many of us thought that promoting instrument flying could result in a better safety record. We were wrong. It just moved the accidents from one column to another. Instrument operations are far more difficult than visual and average GA pilots have not been able to master this as well as we thought they could.

The number of IFR accidents at night is completely out of proportion to the amount of flying done under those conditions. It is generally agreed that maybe ten-percent of the IFR hours are flown at night and more than 30 percent of the IFR accidents happen at night. If anything, that is getting worse with the passing of time.

Night IFR is just not something that the non-professional pilot does often so there is no way for him to be really proficient at it. Is the huge increase in risk really worth it? If there is a real need to fly night IFR then there is also a need to do IFR training and proficiency flying at night.

Airframe failures in flight are truly bad news and they have been and remain a factor every year. They occur as a result of a high-speed loss of control as might happen when a VFR pilot flies into clouds. It can also happen when an instrument pilot becomes distracted and loses control or when a pilot out pranking around lets the airplane get away from him. The result is flight outside the envelope for which the airplane was designed, with both the speed and g-load limits exceeded.

This type accident used to happen mostly in V-tail Bonanzas, Cessna 210s and Piper PA-32 retractables such as the Saratoga. No more. I counted 11 airframe failures and the only certified airplane to show up in more than one was the Piper PA-34 Seneca twin with two.

Twins used to be a rarity in airframe failure accidents so this is unusual. I would say it was a quirk. There was one V-tail on the list, one Cessna 210 and one Piper PA-46 Malibu. Four of the 11 were experimentals. That’s ten-percent of the total experimental airplane fatal accidents which is higher than for certified airplanes.

Ice, thunderstorms and midair collisions have decreased in number by quite a bit more than flying activity. I would imagine that is because pilots have learned to blow the whistles and ring the bells of electronic weather and traffic information systems. At least I hope that is true.

One other flying technique area that comes up short is the missed approach or go-around. The inability of pilots to handle this accounts for ten-percent of the fatal accidents. This clearly illustrates a need in the training process.

Nobody expects that they will miss an approach or have to fly a go-around even though a pilot should always be locked and loaded for either event. Couple that with the fact that anything that is done so seldom tends to take a back seat to other things. That needs to be addressed in training and practice.

When the list of certified airplanes involved in fatal accidents in 2013 is examined, a few things stand out. There are big changes but, with one exception, the changes are likely related to less flying in particular types.

The exception is the Cirrus. Where there used to be a bunch of Cirrus airplanes on the list every year, I found only two for 2013. I think this does show that helping individual pilots avoid the bad stuff is the way to go. Certainly there has been great effort put into helping Cirrus pilots operate their airplanes more safely and I think this is cirrus accidents.

On the other hand, there needs to be an asterisk by this. While there were only two Cirrus fatal accidents in the U. S., there were a total of eight worldwide. That does put a different light on the subject but I don’t exactly know what it means. Maybe the Cirrus group knows of a reason why the airplane is operated more safely in the U. S. than elsewhere.

The pressurized piston singles, the Cessna P210 and Piper PA-46 used to appear frequently on the accident roster. In fact, at one point I calculated that the P210 had the worst accident rate in the fleet with the PA-46 almost as bad.

No more. There was one PA-46 on the 2013 list and no P210s. In the case of the P210, I suspect that is because the airplanes don’t fly nearly as much as they used to. I retired my P210 eight years ago and, even back then, properly maintaining the airplane and keeping it ready for reliable service was a frustrating and almost frightfully expensive proposition.

The PA-46, which is still in production where the P210 is not, probably does better because of an increased emphasis on training and perhaps because pilots have come to understand that pressurized singles can be dangerous as all get-out if not used carefully and correctly.

One jet, the Premier (Raytheon 390), was in three fatal accidents in 2013. Two of the three were apparently flown by owner-pilots.

I mentioned not using computer runs. The Premier gives a good illustration of why this can lead to errors. Query the NTSB database for “Raytheon 390,” which is the official designation, and only one comes up. The other two are listed as Hawker Beechcraft 390 and Beech 390. However a “model” query of just “390” will bring up all three if anybody who is looking knows that a Premier is a 390.

Among older airplanes, there were four Piper Twin Comanches which would be high for the likely number of hours flown by that fleet.

So, the general aviation safety picture continues to evolve as the fleet and the amount of flying continues to change. And anybody who suggests that some technological wonder will bring much change to GA safety flies with rose-colored glasses. It is quite obvious that keeping the head containing the brain in the left front seat well separated from the butt in that seat counts for more than anything on or in the instrument panel.

- From the archives: how valuable are check rides? - July 30, 2019

- From the archives: the 1968 Reading Show - July 2, 2019

- From the archives: Richard Collins goes behind the scenes at Center - June 4, 2019

I have not bothered to read this article. I will tell you that IF the FAA cared about improving GA safety they would act. No instead the FAA is an entitiy to be feared. I actually fear the FAA more than flying my airplance!

First off why do so many GA crashes result in terrible fires that kill more pilots than those that COULD have escaped.

Why does nearly every NTSB report BLAME the pilot instead finding commonailities in crashed in order to improve safety. This is important since they are the reporting agency!

Until the FAA really takes GA safety seriously and acknowleges the role of GA in the overall US economy, nothing will change.

there is an unadulterated assaut on GA airports by Developers. Look at the development at College Park that will eventually result in its removal for safety reasons. A truley historic areodrome.

GA ariports should be protected as National historic sites but instead are prey to the ecroachment of developers who make a quick buck and then are otta there.

There is no real coalition to talk about what I am taking about but I would be willing to spearhead. I am Joro. Hope to hear back from some of you.

joro

Joro – if you’re going to comment on an article, it’s best to read it. :-)

I remain a major critic of the FAA’s bureaucracy, which stands in the way of many safety improvements by making upgrades to our legacy aircraft, as well as the cost of new models, much more expensive than necessary.

However, it is a fact true that most fatal accidents are caused primarily by the pilots, either in terms of specific mistakes in aviating (such as the seemingly intractable scourge of loss of control accidents) and/or in managing flight risks (which is where the weather comes in … the immutable truth is that the weather can’t kill you if you choose not to fly there and then).

The FAA is not to blame for either loss of control or weather related accidents.

Blaming developers is also not productive here – developers are simply not relevant to a discussion of aviation safety. The loss of GA airports has slowed a great deal to a trickle in the last ten years, according to AOPA. There are occasional losses, often highly publicized, in a few urban areas (such as Santa Monica Airport which appears to be on its way out, though it’s not there yet). But the current trend in airport numbers is flat.

In any event, what is far more worrying than the current rate of loss of GA aiports is the current rate of loss of GA pilots and flying activity. Most of the nation’s GA airports today, outside of a handful of major pilot training centers, are pretty forlorn places these days. Sooner or later we have to boost flying activity and the pilot population, or today’s GA airports will simply not be able to justify their continued existence.

Santa Monica Airport? Former home of Jerry Seinfeld’s cars, and Harrison Ford’s planes, and a nifty little air museum? Say it isn’t so!

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/06/17/small-plane-crashes-investigation/10717427/

Ron – that USA Today “hit piece” has been thoroughly discredited by a lot of really knowledgeable writers and analysts, so I won’t try and replicate their debunking of it here. Just do a web search and you can find all you like.

Pilots in command are solely responsible for flying their aircraft safely, at all times, with no exceptions.

Most aircraft accidents are indeed primarily the fault of the pilots, even when there are contributing causes related to the airframe, the avionics, the weather, FAA controllers, and other traffic in the sky. Even when there is a contributing cause relating to an engine, airframe, or avionics failure, in all cases the pilot in command – as required by FAR – makes the final decision as to the airworthiness of their aircraft before they go wheels up. An aircraft for which maintenance has been neglected, or poorly done, or was done illegally, in all those cases the blame falls mainly on the pilot in command.

If the pilot does not understand the correct operation of their aircraft, its limitations, and its systems, then it is the pilot at fault. It is rare in the extreme for an airplane to fail in such a way that the pilot cannot recover or safely land the airplane, and in which the pilot in command bore no responsibility whatsoever for the failure.

We are all charged with managing the risks of every flight we make. Even the consequences of a catastrophic engine failure are not solely the fault of the aircraft, if (as in most cases) the pilot has properly managed the risk factors of the flight. A great illustration is the fatal crash in Taiwan last year of a twin turboprop airliner in which an engine failed on takeoff, but the PIC feathered and shut down the operative engine instead of the failed engine, killing everyone on board.

There are some who continue to insist that GA pilots are getting unfairly blamed for accidents … but when one compares the safety record of commercial and airline flights with that of GA it is plainly obvious that GA pilots come up far short of their professional colleagues. It is no mystery why.

Pilots who have minimal proficiency training (at most a BFR for one hour in the cockpit every two years), or who forget or never really knew how to maneuver their aircraft, or who make terrible errors of judgment as to their and their aircraft’s capabilities – in weather, or traffic … or who do other unwise things (such as low altitude extreme maneuvers, or who take off overloaded, or with insufficient fuel, etc. etc. etc.) are primarily at fault.

The notion that aircraft manufacturers are primarily to blame for accidents, as USA Today asserts, is absurd.

The weakest link in virtually every mode of transportation is the human element. Even in airliners, with their terrific safety record, multiple systems redundancies (including pilots), vast ground support networks, and intensive pilot proficiency certification systems cannot entirely eliminate the weaknesses of the human mind from the accident chain (re: Asiana 214, Air France 447, and Taiwan).

I listened to all of the articles in those links. How can you debunk the testimony of someone who is terribly burned? I could go on, but no time for this.

I had a seat slip back on me while holding short of a runway 21L at TYS. The plane moved forward, I fixed the seat, and never crossed the hold short line. (I typically hold short by many feet.) I shudder to think what my outcome would have been if that had happened 2 minutes later. Don’t even try to argue this with me!

23L

You didn’t say how old the aircraft was that you had a seat track malfunction on … if you’re like most of us, you fly a 30 to 60 year old legacy aircraft whose product liability has long ago shifted to “owner/operator/mechanic” liability. Checking the seats is something done on every preflight, or should be. In most light aircraft, full removal of the seats, including an inspection of the seat track mechanism is required as part of the annual inspection.

So no, a malfunctioning seat track is not an aircraft manufacturer problem. It’s a maintenance and continued airworthiness problem. Two entirely different and unrelated matters.

No light aircraft was ever designed to be mechanically perfect forever without continued routine maintenance and repair.

2006 SR-20

If the seat slipped back and you were able to fix it then you skipped or did not complete properly the seat/seatbelts/shoulder harness item on the checklist. Had the seat rolled back after rotation and the aircraft stalled and crashed……pilot error. Blame where the blame belongs.

Yes, read the article. Richard Collins put a lot of effort into it, and it represents, in my view, the state of the art for GA flying, given the present state of the Government-Industry bureaucracy.

But, one of the things that gets me upset is the phrase: “pilot error”, when I hear of a fatality and it is a pilot with many hundreds of hours of flying and training. Many really good pilots, who are way beyond FAA’s currency requirements have lost their lives. This cannot be totally their fault. The links in the article that I posted a few minutes ago will have you shaking your head.

Also read “Aviation Safety” magazine. In an article last year, they listed many simple improvements that should be made to aircraft. Many of these items are in Cirrus aircraft. In my opinion, the FAA should do everything possible, including cash incentives, to get manufacturers and owners to install these items.

Perhaps, but I did perform that check. I now literally rock the plane while pushing down on the bar, and check it twice. I found that it doesn’t always latch in, even though it feels and sounds like it does.

“GA airports should be protected as National historic sites.”

Based on what? So whatever parcel of land used for an activity an individual has a passion for, should be protected as a historical site? Guess we can protect airports, golf courses, amusement parks, anything else that suits a person’s fancy. Sounds like a variation on the environmental movement,but with a different agenda.

Well written as usual thank you Capt. Collins

Dick Collins and I have disagreed about this in print before. To wit: twin engine engine failure. It is true that if you have an accident after twin engine failure it is more likely to be fatal than an accident following a single engine failure. This is because virtually all single engine failures result in accidents and show up in the data base. But, I can personally verify that if you have an engine failure in a twin and land successfully, the feds never hear about it. There are likely many twin engine failures, both piston and turbine which do not result in accidents and do not show up in the database. Therefore one cannot say with certainty “It has always been true that your chances of being done in are greater in a multiengine airplane after an engine failure than they are after the engine fails in a single. “

A lot of engine failures in singles do not lead to accidents, either, and when it comes down to simple facts related to fatal accidents, my statement is absolutely correct.

You know what would be great? A matrix chart that plots the accidents on a scale. For example I don’t fly at night (at all) and I don’t fly a twin or a turbo prop, so where does that leave me (statistically) on the chart? Did my numbers just went from 1 every 100,000 to 1 every 200,000?

A simple tool on the AOPA website can do this calculation as well… Just my 2 cents.

Liad

It’s surprising that the weather accident rate hasn’t gone down. If there was one technological advancement that should have been truly beneficial, it is the greatly increased availability of weather info.

I guess that doesn’t cure “gethomeitis”, but it sure makes it easier to know what’s ahead.

Except that the FAA & NOAA have eliminated radar sites in the Great Plains and western USA. Can’t get good weather data without operational equipment.

Not sure where you are getting your info. Last time I flew across the US, two weeks ago, the XM weather worked very well. Much better than the old days when you had to stop in at an FSS and then guess where the wx would be in mid-flight.

I think that buried within this article is something that is actually pretty profound – i.e., the recent dramatic reduction in fatal Cirrus accidents. There are three likely reasons for the sudden (within the last three or four years) reduction in Cirrus accidents that are relevant to all personal aviation:

1) A huge emphasis in training pilots to fly their Cirrus airplanes, led by a combination of the Cirrus owner association and the manufacturer itself. Improved training in how to fly the aircraft, including the use its various high technology systems, and also on how and when to use the airframe parachute. This is likely the single biggest reason for the reduction in fatal accidents for this airframe.

2) The safety systems in the Cirrus, including the airframe parachute and other design features (airframe crash-worthy design, g-load rated seats, four point shoulder restraints and airbags, etc.) that make the aircraft more survivable in a hard landing or accident scenario.

3) The high tech aircraft management systems … with the high emphasis on training pilots to use these systems they prove that they are effective in improving flight safety. On the other hand, as Richard points out, if the pilot isn’t familiar with the avionics systems they become an added risk factor.

While we’re not likely to see a massive retrofit of the legacy airframes to add parachutes, it is reasonably practical to upgrade these aircraft with four point shoulder harnesses and airbags. It is more expensive, but still practical, to upgrade with digital electronic avionics systems (such as GPS-coupled autopilots, and ADS-B out/in with displays of traffic and onboard weather displayed on inexpensive portable tablets).

And certainly all pilots could do with more and better training. A new government mandate isn’t called for in this regard, but all pilots should consider doing more training than the minimally-required biennial flight review.

Encouraging all pilots to fly at least an hour or two with an instructor at least every six months could do a great deal to improve flight safety. We all develop bad habits over time, and we all need to upgrade our skills. It’s an added expense, sure, but pretty minimal compared to the expense of a fatal accident … flying more hours itself is certainly no “burden” .. from the pilot’s perspective, flying is not a “bug” but a “feature” … it’s what we love to do.

That took the words out of my mouth. Thank you.

Richard Collins is right about single and twin and about one more gadget going to change everything. It is possible for the plane get out of hand while the gadgets are being programmed. Fly the plane first. One night Camelia and I were over TUL coming to NW Arkansas the weather was really solid IFR. We were in our 182 14R and the controller said he only had two planes the other was a cardinal that ended in RC. That was in the early seventies many thousand hours ago for all three of us and a lot of single engine at night and in the clouds in daytime. Stay with in your capyabilites use common judgement. Get out and burn up some gas it will make you more relaxed on your next flight. This is a recommendation for most of my flight reviews. Richard Collins has been and done that. I bet he still goes out to practice and just fly around. I do. Bill Smith..

Another excellent article, Mr. Collins, I enjoy and learn from them all.

I, too, have long held that singles are safer than twins when an engine fails but hate there’s no reliable way to confirm the statistics. Is there a place we can voluntarily report engine failures that did not lead to an NTSB report? While the information we glean might be suspect, there could still be some knowledge gained. I had one in a single that never made a report and I’m proud of that learning experience even though it was scary at the time.

Honestly, I’d like a twin anyway but it’s just not economically possible for me. There’s something about having two sets of systems that might add safety but it’s arguable whether it outweighs the extra challenges of a twin. The biggest reason is that my wife “would feel safer in a twin”. It’s based purely on emotion but if that makes her more willing to fly, happier at home and more supportive of the investment, I’m in!

Thank you and please keep up the good work!

I (and I suspect many others) still enjoy reading your work. Thank you for another well written and informative article!

While I don’t have any data to back this up, I have the impression that there is far less

flying taking place these days than we used to see. Far fewer airplanes fly overhead. When I take the $100 hamburger flights there is less traffic spotted enroute and fewer planes at the airport restaurants as well.

Guys like my Dad, who started flying in 1942, are the guys that were flying during the General Aviation hey days of the 1960s. So many of the have gone West and those remaining are getting up there in age. Dad will be 90 in November and can still handle the airplane well. His hearing is shot and his Cancer is a formidable foe. Soon, I fear, he too will be gone and there just aren’t enough second or third generation weekend pilots to fill their shoes.

I believe the numbers of accidents will continue to decline until economic factors and human interests change. But you and I, having grown up around airports and airplanes, will have some great memories to enjoy for the rest of our lives. Especially the memories of when we went flying with our Dads.

Here is another thought. One that should get your blood boiling…..

I just found out that the FAA gives grants to airports for 90% of the cost of improvements. Good, so far. But many airports are not even taking advantage of those funds. So, this year Ohio stepped up and made a massive increase (6X,I think) in its budget, to pay for an additional 5% of the cost. Even better.

But the state of affairs in GA is so bad, I wonder if airports will take advantage of that. Lunken field sorely needs more hangars. There is a waiting list a mile long.

So, the reason that I am angry is: Why does the FAA not have a similar program to make improvements to legacy aircraft? What do you think the economic impact on this industry would be if pilots only had to pay 5% or 10% of the cost to add ADS-B? 4-point harnesses? parachutes? etc.? etc.?

Why do the taxpayers have to pay for our safety in our personal airplanes? If you don’t have an aircraft with shoulder harnesses or a four belt restraint system and you feel it would make things safer then pony up, its you and your passengers hides. If i need avionics upgrades just like we just did with ADS-B then no matter what you think if it will benefit you or not and your going to have to fly in controlled airspace you equip for it. If your start taking taxpayer money then other people have an even greater say in your PERSONAL ASSESTS. For me hell no! Now on the airport side your right communities are not using the money and in my home airports management they don’t do it simply because they don’t want someone else telling them how to run their airport even though you never get totally away from it.

Like you, I do plan on ponying up. My comment was directed toward the general population of pilots, who I understand are fighting the ADS-B mandate. But consider this: Why does the FAA invest so much in airports? From the FAA website: “The mission of the FAA is to provide the safest, most efficient aerospace system in the world.” It seems to me that ADS-B is more directly related to safety than GA airport improvements. Perhaps the voters should insist that government agencies fund 50% of the value of their mandates. Such a process might eliminate unfunded mandates… yes? But you make an excellent good point, that the Government gets into everyone’s shorts as soon as they take $1 from them. Good debate.

Thinking a bit more about this: when a person or company gets a deduction or a tax credit on a tax return, that entity does not give up any rights to the Government. Just thinking out loud, would it make sense to push for tax relief in these areas? Possibly a credit worth half the value of a specific airport or safety improvement? That would be less than the 90% that FAA programs invest now.

I’ve seen several studies that show that pilots who are members of their type club (e.g. American Bonanza Society, Twin Cessna Flyer, etc.) have an accident rate almost 8 times better than non-members. Part of the reason for this is that pilots who are already safety-conscious are the ones who join type clubs. However it’s also true that most type clubs do a good job of promoting safety and therefore improve the safety record of their members.

Join your type club and become a safer pilot (maybe not 8 times safer, though).

Bob – Yes, type clubs are a great way to learn and hone our pilot skills. Actually, joining any type of pilot organization that is engaged in regular activities (recreational fly-ins, fly-outs, working with youth, etc.) is a good way to learn, share information, and get better as pilots. Joining and getting active in groups like EAA, RAF, and state pilot associations is a great way to do that.

Richard, you are right about the reduction in GA flying. The U.S. Energy Information Administration’s tally of avgas deliveries provides some interesting information. In 1984 more than 1 million gallons of avgas were delivered per day. In 2006 before the recession, that number had dropped to 646,000 gallons per day. The latest figure for 2014 was 453,000 gallons per day.

Hi Matt:

Thanks for the information. I had not seen those figures,

Mr. Collins,

Your current piece helped crystallize a concern I have had since I decided some time back to try flying one of those clunky-looking airplanes with those very loud, heavy, torque-producing engine things stuck on the front. Many, many moons ago – on my fourteenth birthday – my instructor stepped out of our sailplane and said that his back couldn’t take any more of my landings. Strangely enough, I still always feel a sense of relief when an instructor pulls the throttle to test my metal with a “power off” landing.

Here’s my concern – even in extremely professional and safety-conscious flight schools there persists what seems to me to be a crazy, scary metric: the fewer hours you train – the better. It is a source of pride – and a marketing pitch – to solo and to complete your training with as little experience as humanly possible. Somehow the less you train, the better pilot you must be???

People do studies and scratch their heads about why more people don’t take up aviation as a pass time. Hey guys – the popular wisdom is that our little planes are death traps … and that isn’t far wrong. How about a different approach along the lines of ,”We will sell no wine before it’s time.” Of course check rides, etc. are in place to achieve some level of competence, but the underlying value system seems upside down.

Charlie – you bring up an interesting point … it’s useful to look at the data. If the problem is undertrained private pilots, then the data would say that accident rates would take a sudden jump up right after completing primary flight training (which for most pilots is completed during their first 100 logged hours of flight), and then over time would either level out or gradually reduce as the pilot gains experience and perhaps gains more training.

However, the FAA published a study earlier this year on GA accident rates as a function of logged pilot hours, and it paints a very different picture. The study is found at http://www.faa.gov/data_research/research/med_humanfacs/oamtechreports/2010s/media/201503.pdf.

What the data show is that the lowest accident rate for non-instrument rated GA pilots occurs during the first 150 hours (of which roughly 50-100 hours are logged after earning the PP ticket), then the accident rate starts to increase linearly towards a peak between approx. 500 and 600 hours, where it is about four times as high as the GA accident rate during the first 150 hours of logged time. Then thereafter, the GA accident rate begins a slow decline over the next 1,500 hours, where it remains about twice the accident rate of newly minted pilots.

This result seems to suggest that the accident rate is not because of pilots who don’t receive enough primary training. Rather, it appears (and logically so) that as pilots complete primary flight training, when they are probably the best, most currently trained they’ll be for the rest of their non-professional flight careers, we GA pilots tend to forget our primary training … become less cautious and less risk-averse … tend to become more complacent … and tend to engage in flight missions that they would not have dreamed of with their check ride but a few hours in the rear view mirror.

What I describe is what a lot of us know to be a fact, and entirely consistent with human nature and human behavior.

So I think lack of sufficient primary flight training is not really a problem at all … that’s our safest flying, right after the check ride. It’s all those bad habits we pick up later that hurt our safety record, apparently.

Duane – thanks for your response. I believe we are actually thinking along similar lines. By the time we pass our practical flight test, we have pretty good basic skills, but we have very very little experience. I imagine for most of us those first hundred hours or so are spent pretty close to home. When we start venturing farther afield, we are more likely to encounter situations that are beyond our skill set. So – I guess that I am advocating more experience in more different and more difficult situations rather than basic skills. Just a thought.

For as long as I can remember (and I have a good memory – still), the 500 hour point has been where pilots have the most accidents. So, as in so many other things, nothing seems to have changed.

Thank you Mr. Collins for the article on GA accidents. I am in the process of starting research flight schools in the area to begin instruction and achieve my Private certification. I have been prepping for this for two years. I have read the FAA Airplane Flying Handbook, at least 4 times, Eicheburgers “Your Pilots License” about 10 and just recently, Ron Fowlers “Lessons From the Logbook”, three times. In addition , I have almost memorized your (Mr. Collins’) “Practical Airmanship” Airfacts DVD and also have studied your “Staying Ahead of the Airplane”. I am grateful for your passion for having pilots get it right and Mr. Fowlers’ demand that you have a plan and checklists to follow, to accomplish the mission at-hand, Flying the airplane. Also his detailed instructions on take-offs and landings is excellent.

I only mention this, because I also read, as Mr. Collins, almost every NTSB report printed in Plane & Pilot, Flying, and Flight Magazine. I can learn exactly what not to do and most times, from the accident report, how to prevent it. People to stupid things on earth and in the air. When I become a pilot, I do not want to be stupid, hurry my flight plan preparation, cheat on the pre-flight, ignore an engine or airframe discrepency, or fly when I am not ready or the sky is not ready for me (weather).

I have only flown in two GA aircraft, a Piper Arrow and a Beech 200 turboprop. The latter in a raging thunderstorm while departing Ft. Polk, LA for Shrevesport. It was night, heavy IFR, and these guys were good. After doing some study, probably not an advisable flight. All my other flights have been in the “heavies”. Anything from the 707 through the shrunken 757 (767). Like flying in a toothpaste tube. Thanks to Delta scheduling, I even got to fly through hurricane Agnes (?), on my way to Ft. Dix, that destroyed the Piper factory in 1972. That was in a “stretch” DC-8, nice plane. It was an exciting journey. It was like someone painted the windows battleship gray. Fortunately, the storm was 50-75 miles off of New York. Again the pilots were first class and had the “right stuff”.

When I become a pilot, I want to have the right stuff and not end up in a NTSB report. I have done all this prep to make sure that I don’t.

This is probably boring to the pilots that have 1,000 plus hours or

more in the air. I have learned that being a PIC of an aircraft is a wonderful opportunity to experience the joy of flight, see the world in a whole different perspective and involves a lot of study, training, practice, more practice and the acceptance of the responsibility you have when you start the engine and take off into the “wild blue yonder”. I think one of Mr. Collins videos is “The Prepared Pilot”. That is my goal. Thanks Mr. Collins.

Thanks, Richard. This article says it all and I agree wholeheartedly. There is nothing I can add that will elucidate this subject any better than you did.

I realized that I wrote in my comment “didn’t bother to read”. What I meant was I scanned it as I did not have time at that moment to read the while thing, which I now have. I am passionate that the FAA start helping and stop blaming in thier accidents reports and the title of this well written article got me going. I also meant no disrespect to Richard.

I always appreciate the seasoned, well informed views of Richard Collins.

I agree that training, recurrent or otherwise, helps. Here in Canada night flying risk is acknowledged and requires an endorsment on your license. The ground school reviews the illusions night flying presents and the flying instruction is a lot of instrument work. Might this have saved Kennedy Jr.?

Transport Canada does not require a biennial flight review but does require classroom time and common causes of accidents are a popular topic. ‘Learn from the mistakes of others’ seems to be a common thread.

Weather reporting can be a little uncertain up here. Though I am a VFR pilot I spend about three hours a year with a safety pilot in an effort to preserve some basic instrument flying skills. We have a lot of very dark places at night in backwoods Canada and you are basically on instruments at night.

Thanks Richard for your insights.

It is truly sobering that you have known over 50 people who lost their lives flying. The fact that you kept flying must have meant that you had good reason to believe you weren’t going to join them (unless you were totally crazy, which does not seem to be the case).

My question is this: Of these unfortunate pilots, how many of them could you have predicted their fate? Was it just seemingly random, or were there a high percentage whose skill, personality, and/or behavior made you think “this is an accident waiting to happen”? It seems morbid but is an important question that has direct implications on how (or if) GA safety can be improved.

Thanks for the excellent article.