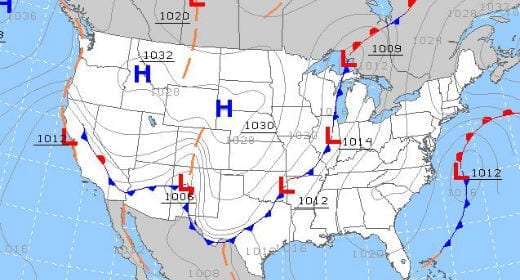

A good weather briefing should include a look at the big picture: fronts, low pressure systems and even winds aloft.

Checking the weather is one of the few constants in aviation. All pilots do it, whether it’s a trip around the pattern in a Cub or a trip across the Atlantic in a Gulfstream. But merely getting a weather briefing isn’t enough; it has to be a good weather briefing to make the flight safer. So what exactly does a “good briefing” involve?

Many pilots base the go/no go decision on little more than the latest radar image and some METAR reports. While these are important, a good weather briefing goes much deeper than this. Flying with only current observations is like performing surgery with only a list of reported symptoms. You know the what, but you don’t know the why.

That’s why a real weather briefing has to include a good understanding of the big picture. Specifically:

- Where are the lows? Dick Collins calls low pressure systems “weather makers,” and for good reason. Lows are responsible for more bad weather than anything else, from low ceilings to in-flight icing. If you know where the low is, you can make a pretty good guess at what the weather will be over the next 24 hours. That’s especially true if you follow the trend–is the low strengthening or weakening? If the weather is forecast to be good VFR but a strengthening low is moving in from the west, it’s unlikely that will hold.

- Where are the fronts and what are they doing? Fronts are prominent on prognostic charts, and for good reason. Next to lows, fronts are the most important weather feature for pilots to consider. A fast-moving cold front sweeping down into warm, moist air should have you thinking about thunderstorms–regardless of what the TAF says. Just remember that fronts don’t go straight up from the surface, so it may be a hundred miles west of its location on the surface analysis by the time you fly through it. Don’t take its position too literally.

- What does the upper air analysis show? If lows and fronts are the weather makers, the upper air wind patterns are the highways that direct them. A glance at the 500mb chart (about 18,000 ft.) can give you a great idea of where and how fast a weather system is moving. Professional meteorologists use these charts for some sophisticated analysis, but even a basic understanding of these charts can provide a lot of insights about where the troughs and ridges are and how strong a low might be.

This big picture weather briefing doesn’t have to be time-consuming–in spite of what some flight instructors might say, there’s no virtue in a two hour weather briefing. If anything, with a good overview in mind, the rest of your weather review should go faster. The radar picture and METARs should simply fill in the details of the picture you already know.

And once you have this overview in mind, you’ll be much more informed as you fly a trip. You’ll be able to read Mother Nature’s signs and understand where your airplane is in relation to that surface analysis chart. Most importantly, you’ll know when to be suspicious of a forecast and where your escape routes are.

So take a moment to review those lows and fronts during your next weather briefing. Far from being an academic exercise, a thorough understanding of the big picture can lead to easier go/no go decisions, fewer surprises en route and more comfortable flights.

- VFR Challenge from Pilot Workshops—A Fuel’s Errand - October 11, 2024

- Interactive Exercise: Test Your Knowledge of RNAV Approach Charts - October 2, 2024

- From the archive:A Pleasant Time - September 16, 2024

The weather is always a factor when I leaave the SF Bay area VFR for Mexico during the winter months… getting to the border with Mexico is difficult at times due to the fog in the central valley and also along the coast.I usually plan on leaving in the afternoon after the fog has cleared and going over the mountains and into the high desert in the early evening….or at night. Now I hear that General Fox airport is going to be laying off Air Traffic Controllers. I hope the controllers are on duty with their radar, at night, when I make my next trip.

where’s the best place to look at a 500MB chart? if i understand correctly, it not quite the same as looking at the winds aloft chart at the 18,000ft level. the regular aviationweather.gov website doesn’t seem to have the 500MB chart readily available.

adam

The 18,000 ft chart is usually close enough for what I use the chart for. A good place to look is Intellicast: http://www.intellicast.com/National/Analysis/UpperAir500.aspx

Look today and you’ll see why that system over the middle of the country is such a mess. Closed low aloft.

On aviation weather.gov, the constant pressure charts (like the 500 mb one) are hidden under the tools tab. If you select the standard briefing, you will find it plus many of the less available weather products. Are they regarded as too in depth for most pilots? I suspect so.