They called them “Race Pilots” back then, but the expression had nothing to do with breaking speed barriers. More than two decades after the Wright brothers made history, only one African American, Bessie Coleman, possessed an international pilot’s license, and she had to go to France to get it. It was the era of Jim Crow laws, which strictly enforced racial separation, especially in the American South. Blacks had to keep their heads low, sit in the back of the bus and in the rear cars of the train. Airlines wouldn’t even allow black people as passengers. And very few flight schools were willing to accept black students. That didn’t sit well with William Powell, who sought to expose more African Americans to the art of flying. In the process he inspired blacks to take a greater role in aviation, and along the way he formed history’s first all-black aerobatic team.

Thin, lanky and invariably well-dressed, Powell grew up in a middle-class black neighborhood in Chicago and studied engineering at the University of Illinois. Before he graduated, however, the United States entered World War I, and Powell joined the Army. He fought with distinction, but was severely injured during a gas attack on the war’s last day, November 11, 1918.

His health impaired, Powell returned to Chicago and went back to college, eventually receiving his engineering degree. “He was a natural-born entrepreneur,” observed Von Hardesty, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum and author of Black Wings: Courageous Stories of African Americans in Aviation and Space History. In the postwar years Powell bought as many as five gas stations and an auto parts store in the city’s largely black south side. But like many young men of the day, he also yearned to fly. Just to go up once—that’s all he wanted.

While attending an American Legion convention in Paris in 1927, Powell got his chance: A pilot took him on an aerial tour of the City of Light, even circling the Eiffel Tower. Right then and there, Powell decided to become a pilot.

Despite the repressive policies that were keeping blacks out of the cockpit in the U.S. at the time, he foresaw new opportunities in the burgeoning field of aviation. “I actually believe that with the proper leadership,” Powell wrote, “Negroes can be systematically trained to the use of the airplane to such an extent that a great airplane industry might spring up.” Not only would blacks avoid the indignation of sitting in the back of an airliner, they could pour thousands of dollars back into the black community by buying black-built planes, forming black-run airlines and hiring black pilots to fly them and black mechanics to fix them. And if they weren’t permitted to land at white-run airports, blacks could build and staff their own airports. In Powell’s mind, separate could amount to equal.

Powell scoured the United States in search of a flying school that would accept him. Though he already had a standing invitation from the Paris School of Aviation, he wanted to learn in America. It was, after all, the nation he had almost given his life for, and certainly gave his health for. First he tried in Chicago, but was turned down because, he was told, white students would walk out if a black man walked in.

Next he tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps. The training headquarters was in Rantool, Ill., just six miles from Urbana, where Powell had attended the University of Illinois. There a lieutenant explained that all Air Corps enlistees were required to have two years of college, to which Powell replied that he had graduated from the university just up the road. Then the lieutenant explained that all applicants had to have engineering degrees. Well, in fact, Powell had majored in electrical engineering.

Then the recruiter cut the bull and told him that, even though he was a veteran, the War Department wouldn’t accept “colored men in the Air Corps,” adding, “I personally don’t agree with this policy…I was reared by a colored mammy, and would just as soon instruct colored students as whites.…But—such is life!” He offered to instruct Powell in his spare time, but Powell refused; he wanted to go full-time.

Powell wrote to flight schools across the nation until he finally found a color-blind school in Los Angeles that would accept him. Its more than 100 students included three from Japan, two from the Philippines, one from China, one from Mexico and even one Hindi. The cost was $1,000, three times the average workingman’s annual salary at the time, but Powell had the cash. He moved his family to L.A. and started flying.

After earning his certificate, Powell founded the first all-black aviation organization in 1929, the Bessie Coleman Aero Club. (Coleman had died three years earlier, on April 30, 1926, after being thrown from her plane during preparations for an airshow in Jacksonville, Fla.) “It was open to everyone of any race,” according to Hardesty. “It also had a lot of women involved in it.” But the club didn’t have many white members, and few had any money. No matter: Powell started holding free evening classes in aeronautics at a local high school.

Meanwhile Powell was networking. He made friends with black entertainers, including Cab Calloway, Lena Horne and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, who were in the area to make “race” movies meant solely for black audiences. He also struck up a friendship with boxer Joe Louis. He explained his mission to his new friends and sought their support—and they gave it, both in donations and public appearances.

Also in 1929, Powell attended the National Air Races in Los Angeles, not sitting in the stands, but manning the emergency truck. He found the competitions so exciting that he decided to put on his own event, an all-black airshow.

Powell set the date for Labor Day 1931. All he needed was a few black pilots to perform. Besides himself, Powell knew of Irvin Wells, a tall, handsome man with a pilot certificate earned through the Bessie Coleman Aero Club. William Aikens—of whom not much is known—filled out the trio, dubbed by Powell the Negro Formation Flying Group. And indeed they flew in formation, though not in aerobatic formation. Two other blacks, Maxwell Love and Lottie Theodore, performed parachute jumps. But the show’s main feature was the Goodyear blimp Volunteer dropping a rose wreath in honor of Coleman.

Nearly 15,000 spectators showed up, or at least that’s the figure that Powell released to the black newspapers (white papers wouldn’t have devoted any space to such an event). Fortunately there were no accidents, which served to demonstrate to the public that blacks were indeed skilled enough to handle an airplane.

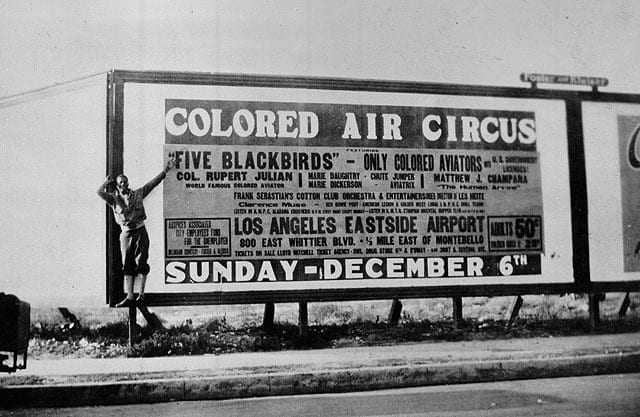

After that success, Powell scheduled a second show, called the Colored Air Circus, which would take place December 6, 1931, at L.A.’s Eastside Airport. This time Powell planned to put together the largest group of black pilots in the air at one time—at least five pilots. He even came up with a name for them: The Five Blackbirds.

To supplement the original trio of Wells, Aikens and himself, Powell approached James Herman Banning, the first black pilot to obtain a license from the U.S. Department of Commerce (the licensing bureau at the time). Banning, the nation’s second black pilot (after Coleman), had come out to Los Angeles to train the trio before the first show. “[He] was a very lovely person,” said pilot Marie Dickerson Coker in a 1983 interview with historian Philip Hart. “I never saw him angry; he was a very sweet person.” But Banning refused to fly in the show unless he got paid, and he also wanted to be the featured pilot. Powell wasn’t inclined to pay him, especially since Banning’s license had expired before he arrived in L.A., and Powell’s organization had helped him renew his certificate and given him 300 hours of free flying time. Still, Banning wasn’t a confirmed “no” just yet.

Powell went on to recruit William Johnson, another black pilot of whom—like just about everyone who flew with the Blackbirds—not much is known. Powell also approached flying student Marie Coker to join his group. A “very high-spirited, entertaining lady,” according to Hart, Coker was already renowned for performing the “shake dance,” a sort of erotic belly dance practiced by the likes of Mae West. Once Coker got her license through the Bessie Coleman school, Powell asked her to become a Blackbird. “This is going to be the greatest thing that you have ever gotten in to,” he told her.

Finally, Powell hired Hubert Julian, who called himself the “Black Eagle of Harlem.” Julian claimed he was a colonel in charge of the Royal Abyssinian Air Force, and boasted of having 1,000 hours in the air. As it turned out, boasting was what he did best. “If someone could rid Julian of his spasmodic outbursts of egotism, there could hardly be a speaker found to excel him,” Powell wrote later. But before he came to that conclusion, Powell made Julian the show’s feature attraction.

Coker drove Julian from New York to California, stopping in Chicago long enough for the Black Eagle to fly a minister and his daughter around the city. Once the two fliers reached L.A., Powell arranged for the mayor to welcome Julian on the steps of City Hall as the nation’s “greatest Negro flier.” Of course, having Julian named the featured pilot didn’t sit well with Banning, who even if he wasn’t getting paid had still hoped for feature billing.

With his Blackbirds lined up, Powell had to find a few airplanes for them to fly. He managed to scrounge up a Challenger Commander, a Hisso-Eaglerock, a Waco 10, a Kari-Keen and a Wright J6 Travellaire from sympathetic owners. Not only were they different aircraft, they weren’t even all painted black. But that was merely a superfluous detail.

According to Powell, some 40,000 people turned out to see the world’s first all-black aerobatic team perform at the first all-black air circus. For the opening act, Julian took off—as a passenger—to perform a stunt billed as a triple parachute jump. In theory, this meant that after the first canopy opened he would cut it away, free-fall for a bit, open the second canopy, which he’d also cut away. Then he’d free-fall some more before opening the third canopy and landing. As it happened, Julian apparently lost his nerve and skipped both cutaways, simply parachuting from the plane.

Following the jump, Julian climbed his airplane to 6,000 feet. Then, according to a local black newspaper report, with “a series of loops, rolls, twists, and turns in his plane, Col. Hubert Julian today has become a favorite with Los Angeles airmen and women.” Unfortunately, that account had been written beforehand. Powell told a different story after the show: “[The] hair-raising stunts…never materialized. He didn’t even make a sharp bank, but soon descended, asking for a glass of water, stating that it was quite different to do all that hard flying and make a parachute jump also.”

After that fiasco, however, the Blackbirds took to the air “and saved the day,” according to Powell. Not five but seven black pilots took off, one by one. Wells went first, then Aikens, Julian, Johnson, Matthew Campana, Coker and finally Powell. They flew to a nearby field and landed—all except for Julian, who later claimed he got lost. After waiting for him, the six gave up and took off once again, flying in a “V” back to the field, then buzzing the crowd in a train, or “follow-the leader,” as Coker described it. She recalled: “[Powell] would lead, the first one would fall off, then the second one, then the third one, and we would make a line and come on back around and make another string and come off. That’s all we did, and that was good enough.”

After each flier landed to enthusiastic applause, Maxwell Love and Marie Daugherty performed parachute jumps. The show received glowing reviews in the press—the black press, that is, since once again the white press ignored it.

Powell now developed ambitious plans for the Blackbirds: They would mount a 100-city flying tour across the United States to promote his vision of black-run aviation industries. Meanwhile, he decided to enter the 1932 National Air Races’ transcontinental competition with Irvin Wells—the first blacks to do so, of course.

Powell and Wells qualified for the race in an OX5 Lincoln Paige, flying at an average speed of 94.7 mph. They joined 56 other teams that had entered airplanes in the competition. Two days before the race began, the pair learned that James Banning was preparing to set out for New York, determined to beat them for the honor of becoming the first black to fly across the country. Somewhat miffed but glad that another black pilot would be in the running, Powell and Wells took off. They crashed in the Sacramento Mountains.

Making their way to a farmhouse that night, they decided not to disturb the farmer (who knows what would have happened if two blacks had showed up late at night), and instead fell asleep outside the house. The following morning a Texas Ranger woke the pair and accused them of murdering a milkman in El Paso two days earlier. They showed the Ranger their pilots’ licenses, also displaying them to a group of shotgun-wielding men who drove up a little later. Fortunately, one of those men was a pilot who confirmed that they were indeed entered in the National Air Races. In no time the locals pitched in and repaired the Lincoln Paige, after which Wells and Powell managed to limp back to Los Angeles.

Rather than embark on his planned cross-country flight at that point, Banning hooked up with Oklahoma pilot Thomas Allen to perform in a series of all-black airshows in Pittsburgh, Kansas City, Chicago, Denver and Salt Lake City. According to the Pittsburgh Courier, Banning would entertain spectators with a “dead-motor landing from an altitude of 3,000 feet,” along with loops and other stunts. They earned about $1,000 a show—astronomical wages for the day. Banning and Allen did eventually become the first black fliers to make a transcontinental flight. Following a 22-day journey in their Alexander Eaglerock biplane, they reached Long Island’s Valley Stream Airport on October 9, 1932.

In February 1933, while Banning was flying as a passenger in a Navy biplane at an airshow in San Diego, the airplane went into an inverted spin. Both the pilot and Banning died in the crash. Before they took off, a local flight instructor had refused to allow Banning to fly the plane because, the instructor said, he was not a capable pilot.

Around that same time Irvin Wells received his commercial license, the first ever earned by a black. But in the 1940s, after 12 years in the air, Wells gave up flying for good and opened a sporting goods store in central Los Angeles. His great-nephew Andre Vaughn remembers playing in that store, though he heard little about Wells’ days as a pilot. “My father used to talk about how he went up with him until his mother put a stop to it,” Vaughn recalled.

In 1935, when Italy invaded Ethiopia, Hubert Julian left L.A. to lead the Ethiopian air force—which then consisted of three airplanes. While Benito Mussolini’s forces overran the African nation, Julian managed to personally destroy a third of the fleet, then returned to the United States. He moved back to Harlem, where he would later brag about training with the Tuskegee Airmen, the first all-black group of Army Air Forces pilots in World War II. Actually, he’d been kicked out of the group. The Black Eagle of Harlem died in 1967. He was followed by Irvin Wells in 1974, Thomas Allen in 1989 and Marie Coker in 1990.

Dogged by complications related to the poison gas he had inhaled in WWI, William Powell died much earlier, in 1942 at the Veterans Hospital in Sharon, Wyo., with his wife and two children by his side. In 1934 he had written a book about his experiences, Black Wings. According to Von Hardesty, Powell “expressed great optimism that aviation would transform modern life—that this same modern technology would offer African Americans a unique avenue to escape racial segregation.” In fact, when Powell’s book was published, there were but 12 black pilots out of 18,041 pilots in the U.S., and out of 8,651 licensed mechanics, just two were black.

Although the Five Blackbirds only performed one show, they demonstrated their skill and talent to thousands of spectators. To blacks, they proved that their dreams of flying could be fulfilled; to any whites who saw them, they showed that a black man or woman could be just as competent in the cockpit as a white pilot. In the short haul, Powell and his Blackbirds opened the American skies to the race-busting pilots who followed.

- Warp speed: birth of an aileron - February 11, 2014

- The $2,400 pair of sunglasses - March 25, 2013

- Fields of vision: carving hills into airports - December 7, 2012

Much appreciation is in order for these early African-American pioneers so that years later an African-American like myself can, without a second thought, walk into my nearby FBO and begin flight lessons.

Wow time to turn this history into a MOVIES, and keep his dream alive.

Yeah–and I’ll write it. Are you listening, Hollywood?–Phil

Interesting read.

I appreciate really this page.

I may give a few comments about Ethiopia. Julian, invited at this time by the Negus and well renowned after a successful parachut jump, crashed in October 1930 the only training plane of the Ethiopian Air Force, a Morane Moth (DH.60M) bought in March 1930 from Jacques de Sibour and his wife Violet Selfridge. The Ethiopian Air Force owned then eight planes of French origin : the DH.60M, 6 Potez 25 and one Farman 192. After his crash, Julian was expelled, the Negus saying that “there are more planes to destroy in the US than in Ethiopia”.

Julian came back effectively in 1935 but the Ethiopians remember him and he was simply forbidden to fly. He trained infantrymen after a fistfight by jealousy with John C. Robinson, the “Brown Condor”, really appreciated as a pilot. Julian left Ethiopia early, in november 1935. The Ethiopian Air Force had then 12 planes more or less able to fly (4 Potez and 8 other planes of civilian origin) and 2 Potez under heavy repair (never repaired).

Consider the struggle of the Tuskegee Airmen, even in wartime, to fly in the service. Had Eleanor Roosevelt not intervened, these trained pilots would have sat out the war. I wonder how many people have heard of Bessie Coleman or William Coleman? Black or white? These pioneers should receive much more acknowledgement.