|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Ever since the completion of the first around-the-world circumnavigation by the Magellan Expedition in 1522, sailors, pilots, explorers, and adventurers of all kinds have been infatuated with circumnavigating the Earth. Boats, planes, balloons, motorcycles, and vehicles of all kinds have made circumnavigations. It was not until 1965 that the first Polar Circumnavigation took place. Since then, only very few aircraft have completed a full polar circumnavigation. One of the first obstacles to consider is the distance required to traverse Antarctica. The shortest route over the South Pole runs from Ushuaia, Argentina, to Christchurch, New Zealand, spanning over 5,000 miles. The alternative route from Cape Town, South Africa, to Christchurch, New Zealand, is over 6,000 miles. This requires a range that very few aircraft possess.

Polar Circumnavigation Speed Record versus Polar Circumnavigation Diploma

The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), based in Lausanne, Switzerland, has maintained aviation records since 1904. FAI issues both circumnavigation speed records and circumnavigation diplomas. Requirements for the diplomas differ significantly from those for the speed records, creating confusion. For example, the speed record for a Polar Circumnavigation requires the aircraft to fly around the world and “shall pass through both geographic poles.” It also requires that “Crossing of the equator from North to South shall be separated from the crossing of the equator from South to North by 120-180 degrees of longitude.”

The Circumnavigation Diploma has different requirements. It states, “The flight must have been made to a control point north of 75º North latitude and a control point south of 75º South latitude.” Furthermore, “The crossing of the equator from North to South must be separated from the crossing of the equator from South to North by 90-180 degrees of longitude.” These are two very different requirements. The Polar Diploma requirements allow for a one-year completion period for the circumnavigation. This makes it possible to complete the northern portion in the summer of the Northern Hemisphere and the opposite summer in the Southern Hemisphere. While the Polar Circumnavigation Diploma requirements are far less demanding than the speed record requirements, as of this writing, only six pilots have received the Polar Diploma. There were two crew members per plane, so only three aircraft — a PC-12 and two TBMs — have ever met the diploma requirements.

The Latest Polar Circumnavigation

I was part of a four-person crew that completed a Polar Circumnavigation Diploma flight in May 2025 in a 1976 Learjet 36A, S/N 022, N31GJ. If the application is accepted, it will be the fourth aircraft to meet the FAI Polar Circumnavigation Diploma requirements. The flight served as a fundraiser for the Classic Learjet Foundation, which is currently restoring Learjet 23 S/N 003, the first Learjet delivered to a customer in 1964. The now-vintage Learjet 36A completed the 26,291-mile flight without any issues or maintenance delays. At the time of the flight, the plane was 48 years old and had accumulated a total of 22,800 flight hours. The same flight crew set the westbound around-the-world speed record for class C1f in April of 2024, also flying a Learjet 36A.

I was part of a four-person crew that completed a Polar Circumnavigation Diploma flight in May 2025 in a 1976 Learjet 36A.

Departure was from Hangar 14 in Wichita, Kansas, the original Learjet factory delivery center, where the last Learjet was delivered on March 28, 2022. A hangar party and a grand send-off from former and current Learjet employees, now Bombardier, made for a festive departure. Brenda Lear was there to speak to the crowd and bid us farewell, presenting our lead captain, Bart Gray, with one of Bill Lear Jr’s custom Learjet baseball caps. The flight was dedicated to Bill Lear Jr, a US Air Force test pilot who had evaluated the Swiss FFA P-16 jet fighter. When the production of the fighter failed to develop, Bill Jr. persuaded his father, Bill Lear, to purchase the project and associated tooling. A few years later, the Learjet 23 was born in Wichita, Kansas.

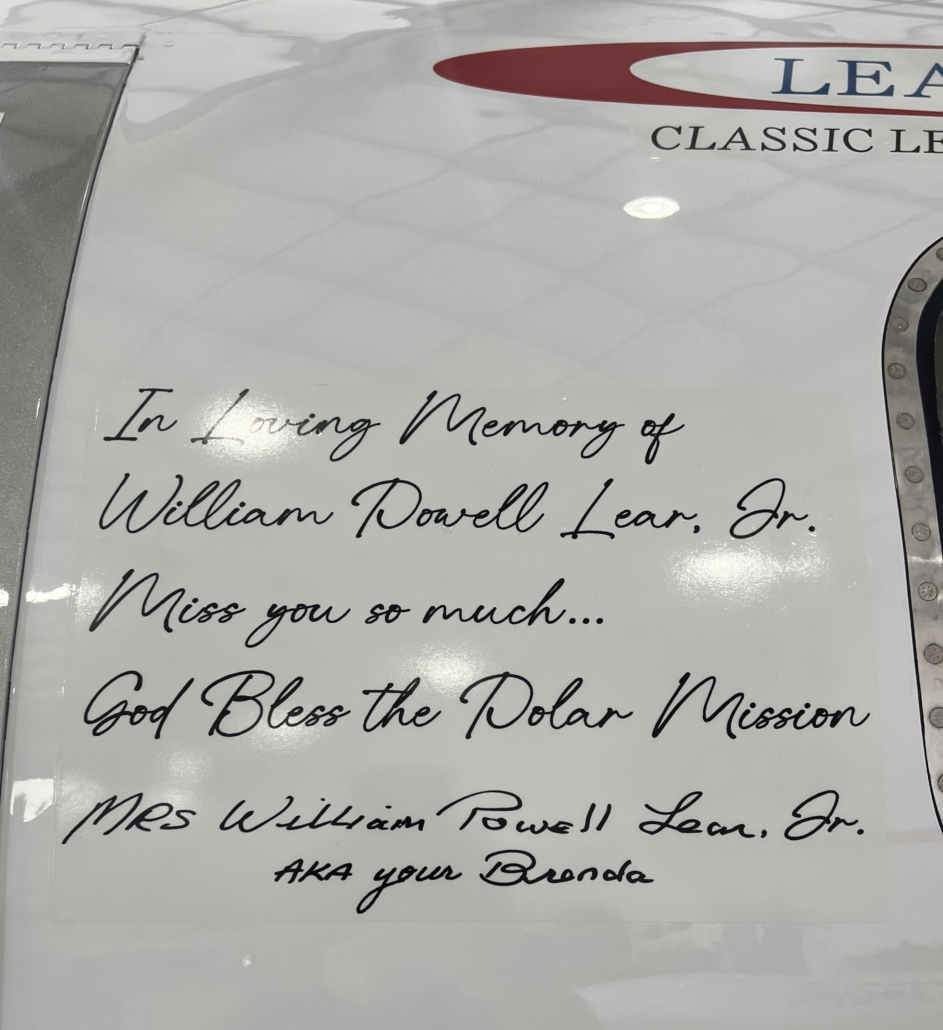

N31GJ was recently repainted white, featuring striking royal blue and black stripes. The engine cowlings are a solid royal blue, with frost-colored ice sickles streaming back from the windshields, windows, and the logo on the tail, honoring the Polar Mission. The fuselage and tip tanks are adorned with colorful decals representing numerous sponsors. One of the major sponsors, Brenda Lear, has hand-written just aft of the door, “In loving memory of William Powell Lear, Jr. Miss you so much…God bless the Polar Mission, Mrs. William Powell Lear, aka your Brenda.”

Flying a twin-engine jet on a polar circumnavigation is entirely different from piloting a single-engine aircraft, yet it still poses several challenges. Although no records are involved, aside from potentially being the first Learjet to venture into the polar regions, we navigated the route as quickly as possible, stopping as little as necessary to keep the airplane focused on its vital mission of providing medical evacuation. We fulfilled the requirements for the Polar Diploma in five days, flying for 58 hours and making 12 stops. A total of 28 overflight and landing permits were necessary, some of which were quite challenging to obtain.

Routing after Wichita included: David, Panama; Antofagasta, Chile; and then Ushuaia, Argentina. From Ushuaia, we overflew Antarctica to 75ºS/68ºW and then returned to Ushuaia. Flight time was 6 hours and 36 minutes, right at the Learjet 36’s maximum. Heading back north from Ushuaia, we made stops in Florianópolis and Recife, Brazil; St. Helena Island; São Tomé; Agadir, Morocco; Shannon, Ireland; and then Longyear, Svalbard. Sitting at 78º North latitude, just landing in Longyear fulfills the requirement to reach 75º North. From Longyear, Svalbard, we made one stop in Iqaluit, Canada, and then returned to Wichita.

One of the challenges of the Polar Diploma is crossing the equator at more than 90º. In our case, we used a waypoint off the west coast of Ecuador, situated at 85º West, as the southbound point. We then secured approval to land at São Tomé Island, located off the coast of Gabon at 6º East, thereby allowing us to cross the equator just a few miles south of São Tomé, fulfilling the northbound requirement by 1º.

One of our more interesting stops was at St. Helena Island, located in the South Atlantic, 1,800 miles southeast of Recife, Brazil. The airport has a requirement that the forecasted ceiling must be at least 1,000 feet above the approach minimums and three miles of visibility to depart for the island. An ETP (equal time point) is required; upon reaching the ETP, if the weather does not meet the minimum requirements, you must return to the departure point. Winds have been recorded at over 90 knots at the airport, and a NOTAM is in effect regarding the possibility of severe wind shear on short final. Additionally, the island receives one flight per week from South Africa on Saturdays, and the airport is closed that day. This situation made planning challenging due to the forecasts, leading to a two-day delay.

We landed back in Wichita on May 5th to another welcoming crowd. In attendance was Wichita Mayor Lily Wu, who presented a Proclamation that stated in part, “Whereas, Wichita, Kansas has been the Air Capital of the World for nearly 100 years. It is also home to Learjet, where Wichitans built the first business jet delivered in North America.” The Proclamation proclaimed May 5, 2025, as “Classic Lear Jet Foundation – Polar Mission Day.”

Polar Circumnavigation Speed Records Recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

The first Polar Circumnavigation flight took place in 1965, when Fred Lester Austin, Jr. and Harrison Finch, both TWA Captains, convinced Flying Tigers to rent them a brand-new Boeing 707-349C, registration N322F, nicknamed “Pole Cat.” Both members of the Explorers Club, they conceived and planned the flight at the Explorers Club headquarters in New York City. The airplane was crewed by a total of five rated pilots, including the chief pilot from Flying Tigers, Jack Martin. There were three navigators, three flight engineers, and 27 passengers, primarily scientists and engineers, including Colonel Willard F. Rockwell, Sr., founder of the Rockwell Corporation, who paid for the flight. Lowell Thomas Jr. was on board to document the flight. Four thousand gallons of fuel were added to the cabin in two tanks, totaling 19,909 gallons. The plane required 10,840 feet to take off. The flight covered 26,230 miles in 57 hours and 27 minutes, setting eight long-distance and speed records while flying directly over both the North and South Poles.

In 1971, Elgin Long, a pilot for the Flying Tigers, became the first person to fly solo around the world via the poles in a Piper Navajo, setting 15 aviation records and firsts. Piper Aircraft produced a documentary of the flight titled “A Man, A Plane and a Dream.”

Pan Am Flight 50, a Boeing 747SP commanded by Captain Walter Millikin, Pan Am’s chief pilot, established a Polar speed record on October 28–30, 1977, in 54 hours and 7 minutes. The flight, which celebrated Pan Am’s 50th anniversary, carried 165 first-class passengers and made stops in London, South Africa, and New Zealand. Among the guests were Miss USA, Miss Universe, Miss England, Miss South Africa, and Miss New Zealand.

Next up is Brook Knapp, who set or broke over 100 speed records, including the fastest time around the Earth in a Learjet 35. In 1983, while flying a Gulfstream GIII, Knapp set two new records: the first business jet to land at McMurdo Station in Antarctica and the first business jet to fly over both the North and South Poles. She is the recipient of several awards, including the Harmon Trophy.

Richard Norton set the C1d record in 1987 in a Piper PA-46 Malibu and was the first to fly a single-engine aircraft on a polar circumnavigation. A U.S. Air Force and TWA pilot, he was also the first to complete a circumnavigation using GPS.

Flying a Bombardier Global Express, TAG Group Vice President Aziz Ojjeh, along with a team of four other pilots, beat the 31-year-old Pan Am record for speed around the world via the poles by 19 minutes in 2008.

In 2016, Gordillo Miguel set the around-the-world speed record via the Poles in category C1c, flying a Vans RV8 that he built in his garage in Spain. To cross Antarctica, he flew from Hobart, Tasmania, to Ushuaia, Argentina, stopping at Mario Zucchelli and Marambio Bases, and flying directly over the South Pole.

Bill Harrelson shattered Richard Norton’s category C1d around-the-world via the Poles record in 2015 in his Lancair IV. He also broke Max Conrad’s 58-year-old record for the fastest trip around the world by more than 19 hours in 2019. Bill tested his modified Lancair IV, which had a fuel capacity of 361 gallons held in 10 tanks, by flying non-stop from Guam to Jacksonville, FL in 38 hours and 40 minutes, covering over 7,000 miles.

The most recent and current speed record holder for its weight class is Captain Hamish Harding, along with a crew of three, who completed a full Polar Circumnavigation in a Gulfstream G650ER named “One More Orbit” in 2019. The flight departed from Kennedy Space Center on July 9th, marking the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing and the 500th anniversary of the Magellan Expedition. With just three stops and a total flight time of 46 hours and 40 minutes, this record will be difficult to beat.

Other Significant Polar Circumnavigations

In 1968, a Modern Air Transport Convair 990 airliner, named Polar Byrd I, flew over both poles with 70 passengers and crew. The flight commemorated the 40th anniversary of Admiral Richard Byrd’s South Pole flight. The plane did not set any speed records but was the first commercial jet to land at Antarctica’s McMurdo Station and the first commercial charter from the U.S. to land in Russia. Former Air Force One pilot Harold L. Neff was the lead captain. Seventy passengers paid $10,000 each for the flight, which landed on all seven continents.

Dick Smith was the first person to fly solo around the world in a helicopter and completed an epic polar circumnavigation in a Twin Otter in 1988. A member of the Australian Geographic Society and the Explorers Club, Dick published a beautiful and detailed book titled Our Fantastic Planet, Circling the globe via the Poles with Dick Smith. The book has the following dedication: “This book is dedicated to those intrepid Soviet expeditions who hauled fuel for my aircraft from their coastal station at Mirnny, 1400 km across the Antarctic ice cap to Vostok. Without their country’s cheerful and generous help, I could not have fulfilled my ambition of encircling the globe, and this story of an enlightening journey would not have been told.”

Robert DeLaurentis, flying a Rockwell Turbine Commander 900 named “Citizen of the World,” completed a flight over both poles in 2022. The journey was called “One Planet, One People, One Plane: Oneness for Humanity.” The DeLaurentis Foundation raises funds for aviation-related charitable causes, and Robert visited numerous schools and students around the world during his epic flight. Robert is also a member of the Explorers Club.

No piston-powered aircraft has met the requirements for the Polar Diploma. Only four piston planes have ever satisfied the Polar Speed record requirement. Miguel Gordillo and Bill Harrelson’s planes were classified in the experimental category, while Elgin Long’s was a twin-engine Navajo. This leaves Richard Norton’s Piper Malibu as the only single-engine piston production aircraft to have ever completed a Polar Circumnavigation of any kind, 38 years ago.

Circumnavigating the globe is the ultimate testament to human ingenuity and aviation mastery, but the polar route stands alone as the Mount Everest of flight. On these flights, courage meets the curvature of the Earth. Remarkably, the excellent safety record among these intrepid earthrounders not only reflects advanced technology but also highlights the reverence with which they approach the skies: meticulous planning, deep respect for weather, and an unyielding commitment to safety. As the horizon continues to beckon, one question lingers in the thin air above us all: Who will be next?

- VIA The Poles: Journey Around the World’s Ultimate Flight Path - August 27, 2025

- The European “28 Day Holiday License” - September 11, 2023

- Flying for Ukraine Air Rescue—small planes, big mission - August 29, 2022

One correction: The time to complete the Polar Circumnavigation Diploma is now 150 days not 360.

Another small correction. The 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing would be July 20, not 9.