|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The day after Old Piet fired me—and Zingi un-fired me—I was about to climb aboard my old 500cc Matchless thumper to go home, when Zingi shouted from his office, “See you at the Hunter’s.” I realized this was not an invitation, but an order to meet him at the pub at the end of the road.

We settled on the veranda. Zingi’s tall, amber glass of Windhoek Lager dripped condensation as he leaned back comfortably. I sat on the edge of my chair, holding a Coke bottle in both hands and wondering what this was about. I was the hangar rat—far too lowly a human to mingle with Zingi on a social level.

“Relax,” he said. “I’m going to tell you a story about Mr Piet, so you understand how Placo works.”

He was about to pull me into line. He had given me the job, so my miserable performance reflected directly on him.

Here is the story Zingi told me in the fading light on the veranda of the Hunter’s Retreat.

At the end of WWII, Zingi and Piet were both young Second Lieutenants in the South African Air Force. One moment they were zipping through the Mediterranean skies in their Spitfires, frightening the locals; the next, they were unemployed.

They said goodbye on the smoky platform of the Pretoria railway station. Each had his worldly goods in a kitbag and £20 in his pocket—a gratuity from the SAAF.

The train hissed gently as Zingi climbed aboard. He was heading to the coast to look for a flying job. Piet said he was bound for America, where he planned to get the Piper aircraft agency for Southern Africa.

Piet took the train to Cape Town, then walked to the docks. There he found an unpaid job as second radio operator on a ship bound for the USA. The voyage took four long weeks before they docked in New York.

Next, Piet hitchhiked 200 miles inland to the little town of Lock Haven, Pennsylvania—the home of the Piper Aircraft Corporation.

His timing was perfect. William T. Piper had been building Cubs flat out for the services. Suddenly the war was over, and he found himself with acres of airplanes and no customers. The military didn’t need them, and civilians had no money. Piper was facing ruin.

When his secretary buzzed to say there was a South African in the waiting room who wanted to buy 300 airplanes, Mr. Piper put champagne on ice and offered his visitor a Cuban cigar and a royal welcome. But his joy quickly evaporated when Piet explained that he possessed nothing more than £12 left from his gratuity.

Still, Piet said he would like to take the airplanes to South Africa and sell them, promising to pay Mr. Piper for each one as it sold.

Amazingly, William T. Piper and Pieter van der Woude shook hands on this outrageous proposal.

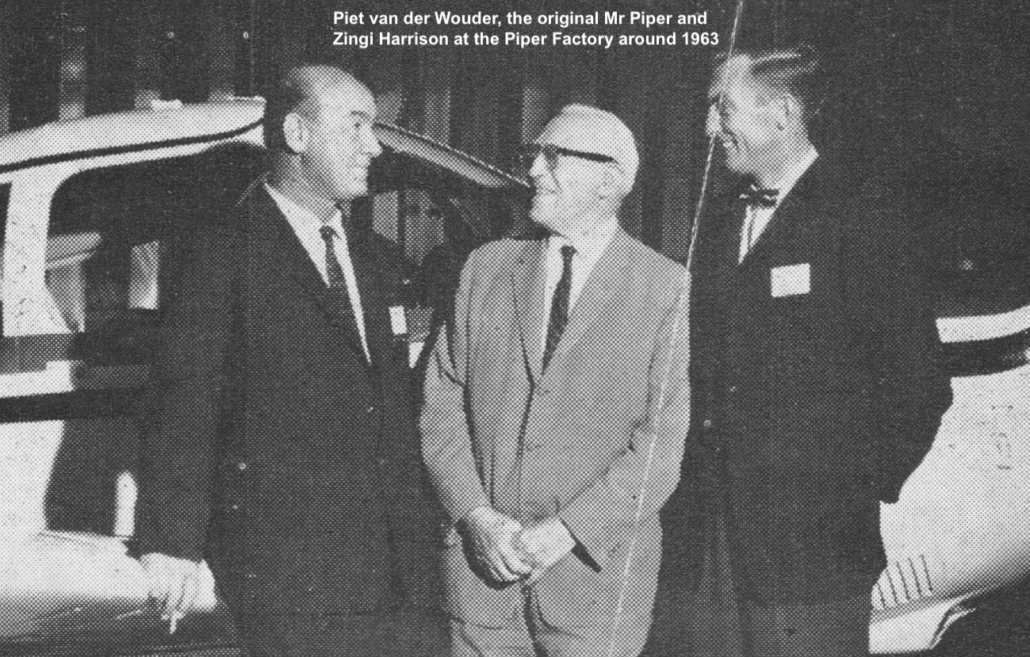

It turned out to be the best deal either man ever made. For many years, Piet’s company—Placo (the Pretoria Light Aircraft Company)—was the best-selling Piper dealership outside the USA. Old Piet and William T. Piper would remain firm friends for the next 25 years, until Piper’s death in 1970.

But Piet still faced a problem: 300 airplanes in America, and no money to get them to South Africa. No one was lending money just after the war. Piet, however, saw no problem. He bought a ship, promising to pay the owner when he reached Cape Town. Then he hired a crew straight off the New York docks, promising to pay them when they arrived.

They loaded Piet’s Cubs and set sail across the Atlantic.

When they docked in Cape Town, Piet sold the ship for enough money to pay the previous owner, pay off the crew, cover the railways for transporting the airplanes to Pretoria, and rent a hangar. He then stripped 50 Cubs for parts, boxed them up, and sold the remaining 250 aircraft one at a time for £425 each. That was about half the price of a fancy motorcar, so they sold extremely well.

Each time he sold an airplane, Piet sent £420 to Mr. Piper and put the remaining £5 profit in his back pocket. But the real profits came when his customers needed spares and maintenance.

Back on the veranda at the Hunter’s, only a glow remained where the sun had been. Zingi downed the rest of his Windhoek and wiped the back of his hand across his mouth. He suggested that I let the history of Placo seep into my soul, and urged me to use it as a guide for my future thoughts and actions.

He went down the wooden steps, paused, and half turned. “Whatever you do in life, give it a full go.”

I watched as he moved across the lawn and faded into the darkness.

- Old Piet and Mr Piper - October 20, 2025

- Hired and Fired - September 26, 2025

- Zingi and the Auster - July 16, 2025

Awesome bit of history there;

Thanks.

Thank you for sharing this amazing piece of history.

In those days, trust was more important than money.