|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“What happened?” It’s the question most pilots dread, because it usually comes from a well-meaning but uninformed person when they read about an airplane crash. Even worse is when the crash involves a celebrity and a small airplane. I shouldn’t be surprised—YouTube is overrun with instant “analysis” videos about every accident, so friends and family expect us all to weigh in with our own opinions—but I still hate it.

So I was a little grumpy when a friend asked me that question a few months ago, in this case regarding the September 18 crash that killed Nashville songwriter Brett James. It’s easy to see why non-pilots might feel confused or even scared when they read news stories like this one from People Magazine (sorry, it was one of the first links on Google) that talk of “the small craft spiraling out of the air.”

The reality is much simpler than most in the media imagine, although certainly no less tragic: it was yet another go-around gone wrong.

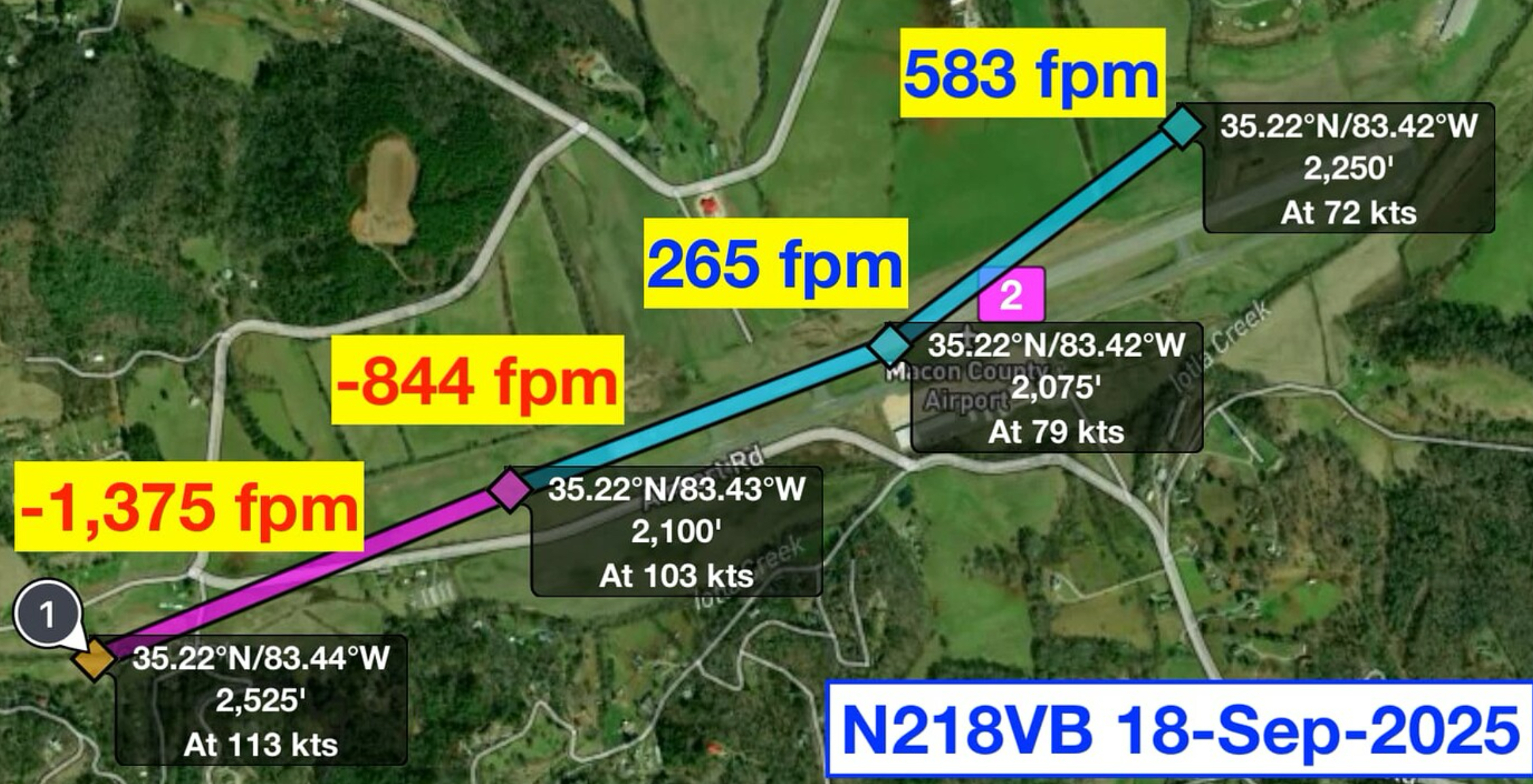

We should wait for the final NTSB report to be sure we know all the details, but the ADS-B data paints an all too familiar picture. Just look at the image below (courtesy of the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association and their excellent YouTube video on the crash). The pilot flew an unstable approach, with a high descent rate (nearly 1400 fpm—twice as steep as recommended) and a high approach speed (113 knots groundspeed—easily 25 knots too fast). Recognizing the mistake, he made a smart decision and aborted the landing. But then things unraveled quickly, as the airplane got too slow during the go-around and veered left of centerline. It stalled, started to spin, and crashed, killing everyone on board.

I was grumpy with my friend because I hate the obsession with instant analysis, and he made me participate in this ugly trend. I was grumpy because this accident hit a little close to home, killing a father who was flying his wife and daughter in a Cirrus SR22 (something I do often). But I was mostly grumpy because go-around accidents happen far too often—and they are eminently preventable. This is one problem we should be able to solve.

Defining the problem

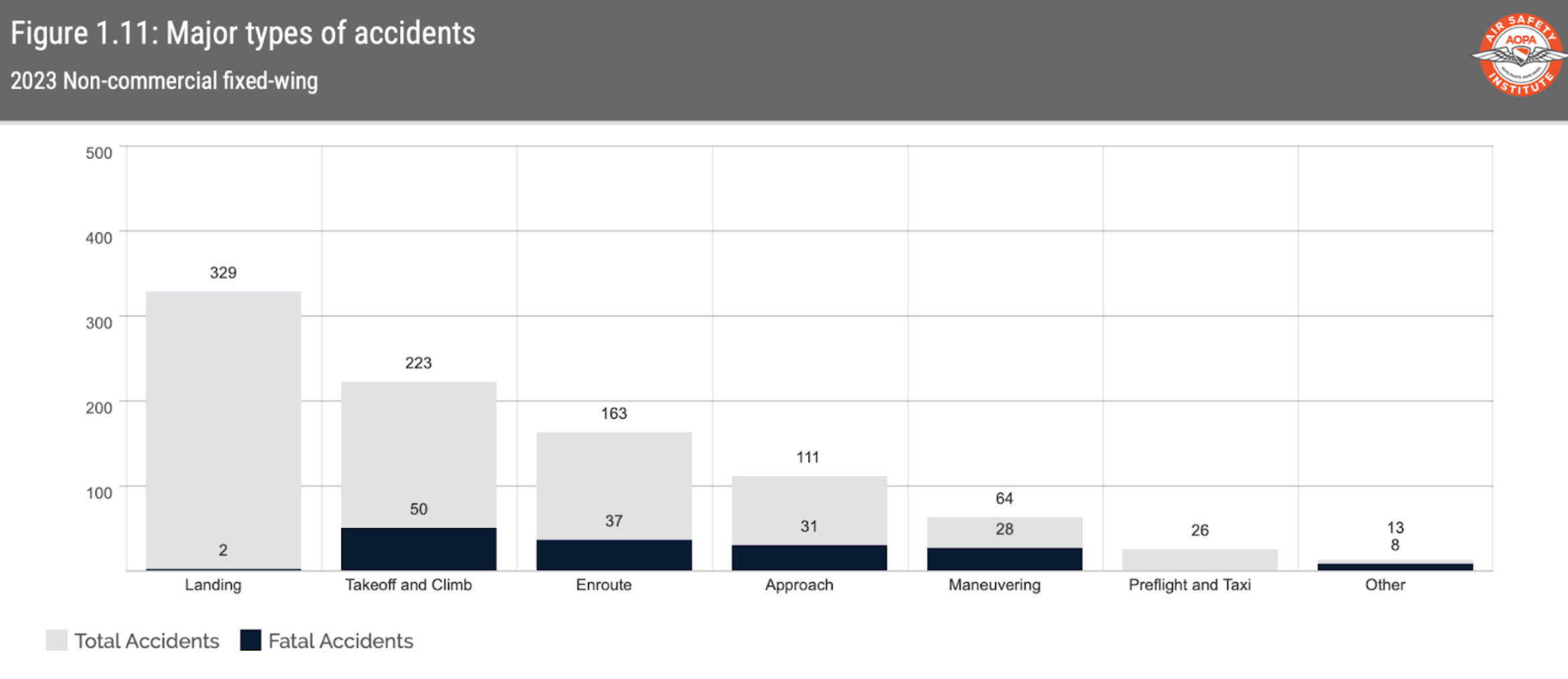

The latest McSpadden Report from the AOPA Air Safety Institute shows reasons for both hope and worry. The overall safety trend is positive, with the general aviation accident rate down 27% since 2014. That is huge progress (and the subject for another article), but some accident types seem resistant to this progress, like go-arounds. While landing accidents make up more than half of all accidents, they are rarely fatal. Takeoff and climb accidents (where go-around accidents usually get assigned), are less common than landing accidents but far more likely to be fatal. In fact, it’s the leading phase of flight for fatal accidents.

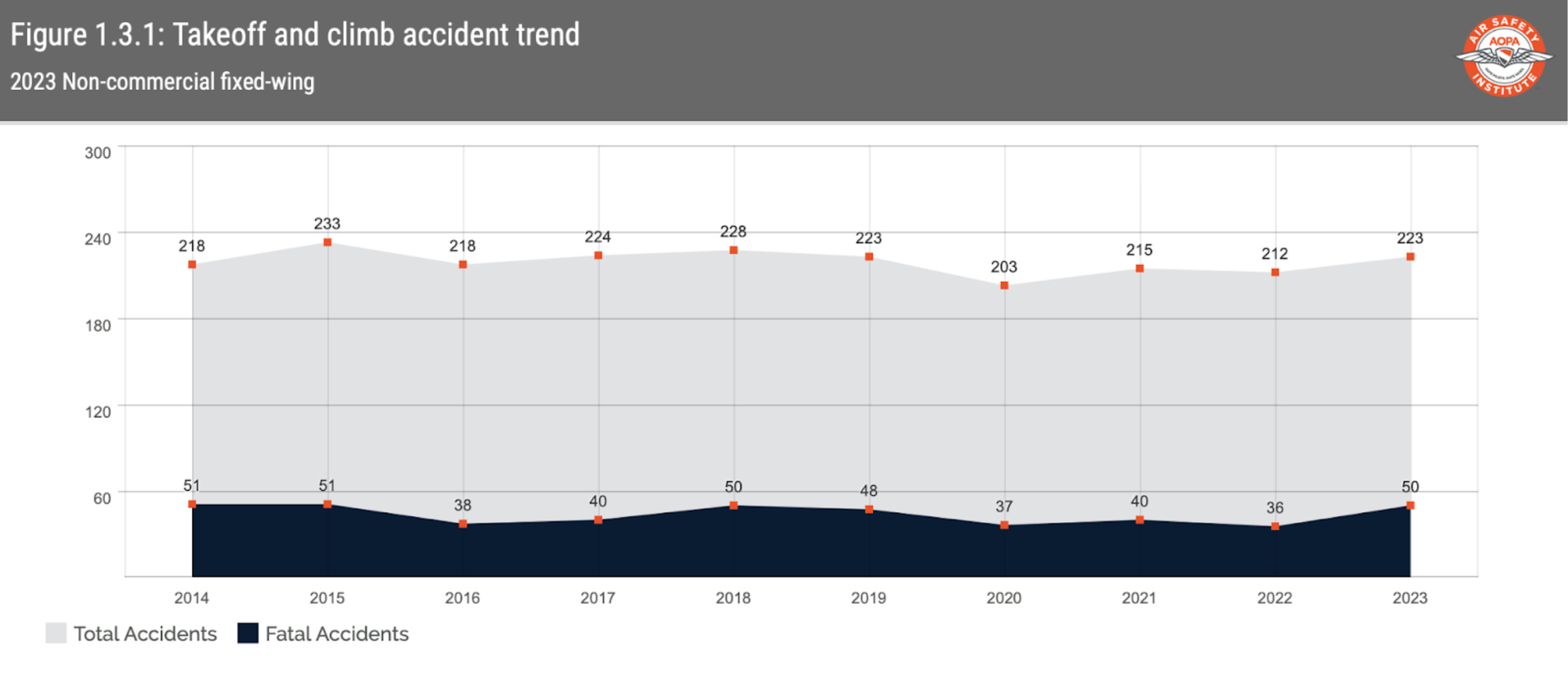

The trend for these accidents is not encouraging, as they are essentially unchanged over the last decade while other categories decline. We can debate whether technology has improved safety in some areas (I think it probably has), but in this phase of flight the answer is a resounding “no.”

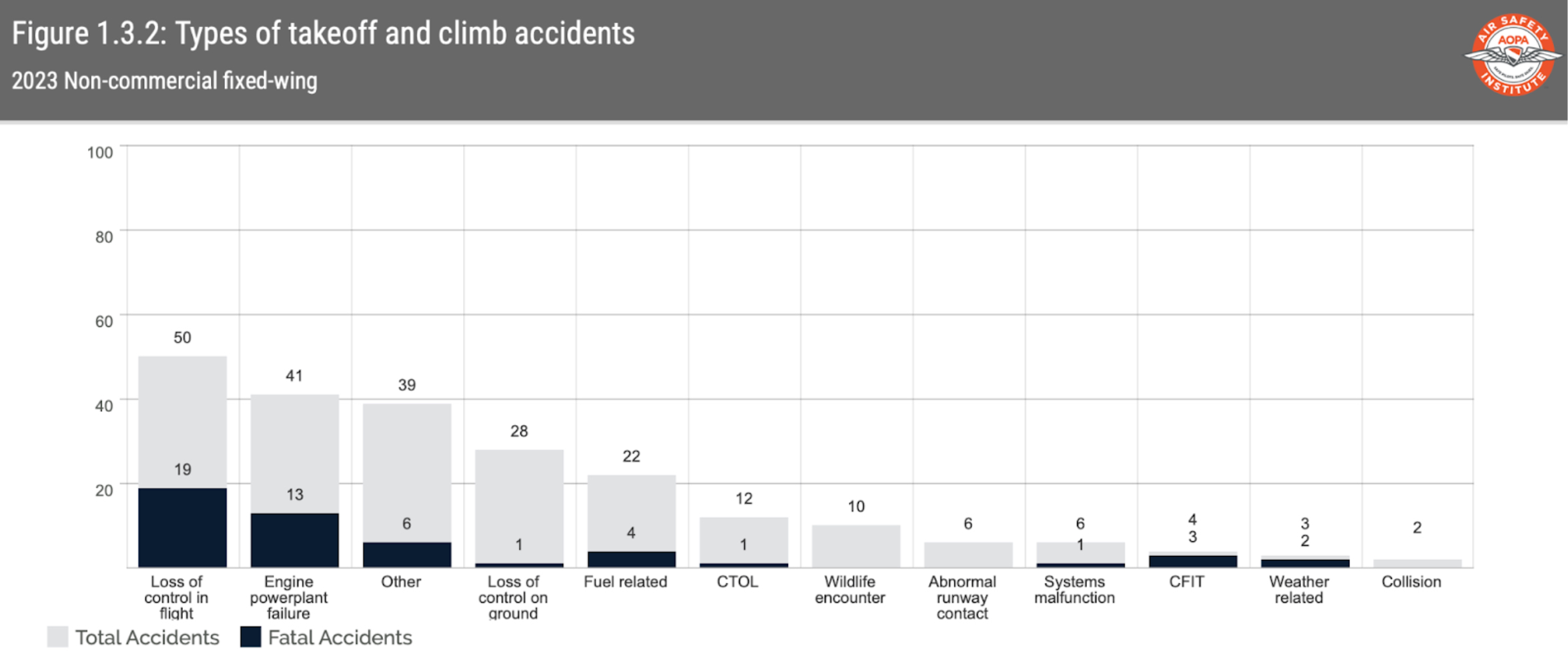

What happens during these takeoff and climb accidents? Loss of control is the leading cause. It’s worth reiterating that not all of these are go-arounds—in fact, most of them are not—but there’s clearly something going wrong with pilots’ ability to maintain control during initial climb.

This isn’t a weather issue, by the way, as 94% of takeoff and climb accidents happen during day VMC conditions. It’s also not really a matter of pilot experience: 44% of these accidents had a Commercial or ATP on board.

More granular studies show that go-around accidents have in fact increased over the last two decades. Even more damning, a detailed report from the Flight Safety Foundation shows that even professional pilots struggle, with only 3% of unstable approaches leading to a go-around, and some of those coming too late. We seem to hate go-arounds, and then we stink at them if we do one. That’s a vicious cycle.

Go-arounds are a particular problem for pilots of high performance airplanes—the NTSB reports are filled with SR22s, Bonanzas, and single engine turboprops losing control. This is hardly surprising, since these airplanes have high horsepower engines that put out lots of torque at full power. They also have faster cruise speeds, so it’s much easier to be fast and high on final, causing a go-around in the first place.

How to prevent a go-around

Those unstable approaches are a great place to start our work, because you can’t have a go-around accident if you make a safe landing. I’m in no way arguing that go-arounds are bad, and sometimes you have to abort a landing for reasons beyond your control, but we should acknowledge that many of these tragedies are downstream from our inability to fly consistently good approaches.

Some pilots get very particular about the definition of “stable approach,” and airlines have black and white rules for when an approach should be discontinued. That’s fine for larger airplanes, but I think most GA pilots should focus on one thing: airspeed control. The ability to fly the correct approach speed (ideally to within +/- 5 knots) is the single best predictor of a safe landing, and a skill that translates to almost all phases of flight. It takes practice, but is hardly difficult if you focus on it.

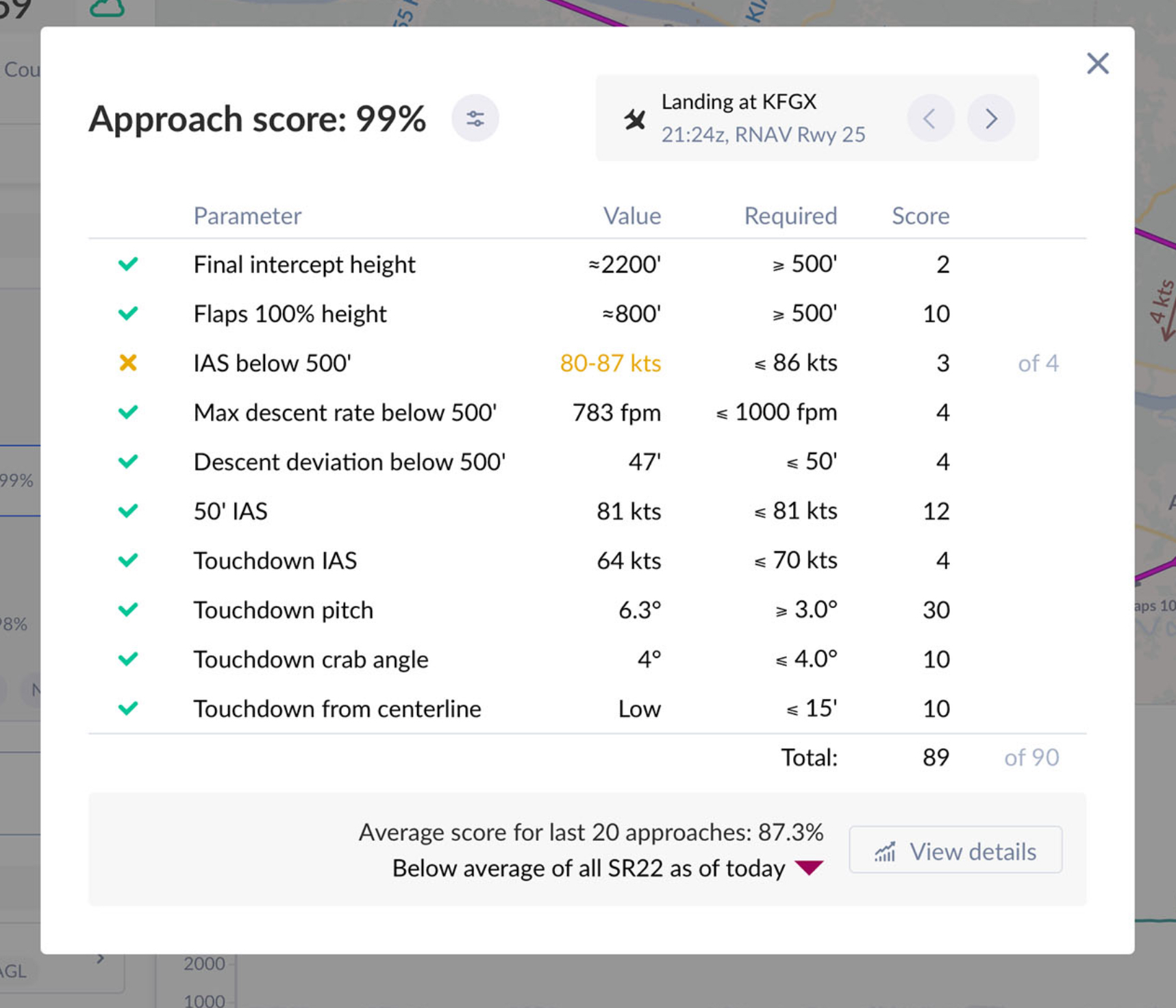

This is now easier than ever, thanks to the latest generation of flight debrief software. Both ForeFlight and FlySto offer affordable and nearly automatic tools for scoring your flights on a range of metrics. You can record data either with glass cockpit avionics like the G1000 or portable ADS-B receivers like the Sentry Plus.

I’ve been particularly impressed with FlySto, which delivers an approach score for every flight that summarizes airspeed control, descent rate, pitch angle, and centerline drift. It even compares your flight to an average of other FlySto pilots who fly the same aircraft type. There is nowhere to run and nowhere to hide with this free app: if you flew a bad approach, you will see it clearly.

Once you have this data, it’s much easier to practice the things that really matter. If you’re struggling with airspeed control, spend some time on slow flight or constant airspeed descents.

How to fly a safe go-around

Even with the best airspeed control, go-arounds are sometimes unavoidable (my last “real” one was caused by a group of deer on the runway, who were totally unconcerned about my approaching airplane). So if you do have to go around, the Flight Safety Foundation report suggests the sooner you decide the better; most pilots probably feel more comfortable making a go-around from 300 feet than 30 feet. Either way, this is a time to be decisive. With extremely rare exceptions, there is no time to change your mind once you add power and start to climb. Forget trying to “save it” and focus on aircraft control.

Breaking it down a little more, a good go-around involves five steps. Each one, and how it’s performed, matters.

1. Add power—smoothly. Just like legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden used to say, “Be quick, but don’t hurry.” In other words, you want to push in the throttle and start climbing as soon as you can, but no sooner. Many go-around accidents are caused by a near-panicked reaction from the pilot, with a rapid increase in power that leads to a rapid increase in torque and p-factor. There’s nothing stabilized about this type of flying. Cirrus advises that pilots should take four to five seconds to add full power on the takeoff roll; something similar is good advice for go-arounds.

2. Pitch up—but not too much. Step two seems so simple, but it’s often where the accident chain begins. A typical NTSB report reads: “the pilot appeared to initiate a go-around; the engine power increased, the airplane’s nose pitched up sharply, the left wing dropped.” The key word here is “sharply,” because that causes a rapid loss of airspeed (especially with full flaps), from which a recovery becomes nearly impossible. Learn what a typical climb attitude is in your airplane, both for takeoff and for go-around configurations, so you have a specific number to aim for. In most GA airplanes that will be around 10 degrees, and yet many NTSB reports show the accident pilot pitched up to 20 or even 30 degrees—a dramatic and disorienting view out the window! Trim plays a critical role here, because full flaps and full power with trim set for landing can create a powerful back pressure on the yoke. Be prepared to push forward and start trimming nose-down.

3. Push the rudder—hard. Have you ever been scolded by an old-timer about lazy feet? It’s no fun, and I have a pretty low tolerance for speeches about “back in my day,” but they are absolutely correct on this one. The critical mistake in most go-arounds, the one that gets pilots killed, is lack of right rudder to offset the increase in engine power. If you doubt me, just read some accident reports: the crash site is always to the left of the runway. Modern airplanes will tolerate uncoordinated flight pretty well, but not with full power and low airspeed. Certainly a tailwheel rating or a glider certificate is a great way to improve your rudder skills, but even simpler is to imagine your right foot being connected to your right hand: when your hand goes forward to add power, so does your right foot to add rudder. If your airplane has a yaw damper, turn it off once in a while and practice adding rudder during a full-power climb.

4. Retract the flaps—but not too fast. If you’ve smoothly added power, pitched up to your target attitude, and kept the airplane coordinated with right rudder, there isn’t much more to do. Yes, you’ll want to get the flaps up, but there really isn’t a rush. Airplanes can and do fly with full flaps, so unless you’re in an old Cessna with 40 degrees of flaps on a 110-degree day, make sure the airplane is stable and accelerating before you make any configuration changes. When you do, avoid the temptation to retract the flaps all at once. Most airplane checklists suggest changing one flap setting at a time and not fully retracting them until clear of obstacles. Dumping all the flaps right at the moment you pitch up can lead to a nearly instant stall.

5. Turn—only when things are stable. One final step is one should not take: turn. If you’ve just aborted a landing and are climbing, there’s no reason to make a turn until everything is stable and the airspeed is safely at or above Vy. Stall speed increases rapidly as bank angle is increased, so take that variable away entirely. Turns, talking to ATC, and checklist usage can all wait. Fly the airplane.

Practice can make perfect

Reading this five-step process makes a go-around sound easy, and it definitely can be—but only if you practice. That’s something that doesn’t seem to happen very often once the Private checkride is complete. Fortunately, go-arounds can be practiced in any airplane and on any flight, and can easily be integrated into a flight review or instrument proficiency check. The key is to make these scenarios realistic, in particular with some element of surprise. A real go-around will probably not be one you expect, and you may not like your performance as a result.

Consider one go-around accident that was caused by a pilot’s confusion, probably due to a large dose of adrenaline: “During the go-around, the pilot initially thought he had pushed the throttle control full forward, but when ‘nothing happened,’ he looked down and realized he had pushed the mixture control forward.”

Eliciting a reaction like that requires another pilot or a flight instructor in the right seat, one with some creativity. My favorite tip came from a particularly devious flight instructor who got to know the controllers at a nearby Class D airport. He would call the tower before a training flight and tell them to surprise the pilot with a go-around at some point during landing practice. Hearing it from ATC instead of your right seater, and having it be truly unexpected, is great practice.

Go-arounds are the ultimate example of an easy but unforgiving maneuver. The good news is, the more comfortable you are with go-arounds, the more likely you are to do one when needed.

- Use it or lose it: the instrument rating is not an insurance policy - February 18, 2026

- Go-arounds don’t have to be hard - December 8, 2025

- Guard frequency in the age of social media - October 13, 2025

“most pilots probably feel more comfortable making a go-around from 300 feet than 30 feet.”

This. I know I don’t practice go-arounds at 30 feet (I believe the go around in question was performed at 36 feet).

There is a huge difference between flying low and slow and doing a go-around than at DA/MDA. The margin for error gets less and less as you get slower and lower. I *suspect* the majority of go-around accidents are from pilots initiating them at lower altitudes too, but I could be wrong.

I agree with the content of John’s article, but he could have explained the correct steps to take in the event of a go-around, as there are many different (right and wrong) arguments and opinions on this subject. 1. Power

2. Gear up

3. Speed increasing

4. Flaps up (in steps: never use full flaps before DA/MDA or if landing is realy ensured)

5. Reaching Vy then pitch up 7.5°

Best

Walter

Good points, however not being fully configured (assuming landing with full flaps is planned) is cause for a go-around below 1000′ agl ( originally was 500′, VFR) by my company’s ops rules…understand in piston twins on one engine delaying flaps til landing assured is good procedure.

Another great article, John. I’m a midlife student pilot prepping for my checkride and this is a timely reminder to not only hone the go-around procedure now, but to consider it part of my regular rotation of practice beyond the checkride. The statistics on the accidents are sobering; but a timely reminder that the element of surprise plays a role in our performance. This makes having the go-around procedure trained to “muscle memory” even more crucial. Thanks for your insights.

Thank you for a great article. I am a low hour private pilot training on my instrument rating. . I just had a failed go around and crashed my SR22 as I rejected my landing. My approach speed was 81 and stable. My cirrus approach score was 98%. Winds were 6 knots headwinds with minimal crosswinds, and I had 3 people with me and the heaviest person was seated in the back, resulting in a very aft CG which made the pitch control unstable and the plane more easy to stall. I initiated the flare just like I always did but the plane stalled 5 ft above the ground and we touched down with a bounce. The plane was banking a bit to the left and was well to the left of the center line. I was worried we would end up on the turf left of the runway. Instead of accepting the landing and pushing the nose down a bit and applying right rudder and aileron , I decided to initiate a go around. I suspect I did not push the yoke forward enough, did not push the right rudder enough and we ended up barely getting airborne and spinning in slow motion to the left and crashing left of the runway and taxiway and the landing gear smashed into a concrete ditch and we came to the ground. Fortunately, we all walked out unscathed. The plane was badly damaged. I am going to practice my slow flight maneuvers more often now.

Glad you’re OK Sam. The amount of forward yoke and right rudder required in an SR22 is significant—if you’re used to flying in trim all the time (or with a yaw damper), it can be quite a shock how aggressively you have to move the flight controls. Just another vote for practicing it.

Great article, and when I teach this missed approach number one is “fly the airplane” 1. Smoothly add full power, and stop the decent. 2. When positive rate is achieved, then you can start cleaning up the airplane and this can vary with aircraft flown. 3. Most certainly start with retraction of the flaps and trim to best attitude of the airplane. Note; many of the retractibles will loose lift when the gear cycles, so know your airplane.

4. Positive rate and climb away from the problem. At altitude you can decide what to do and how to clean up yourself. FLY THE AIRPLANE!!!

TOGA and follow the flight director if you have it.

Maybe I’m the only one but it seems that almost all of my go arounds have been in ground effect. Be it gusting crosswinds, unexpected turbulence or a bounced landing. With 40 degrees of flap on my 172A I need to get rid of some flap to accelerate right after I add the power. I then treat the go around as a soft field take off in ground effect

My suggestion is to go up with a cfi and learn to do slow flight with full flaps. Then add full throttle (carb heat off) maintain a level pitch attitude. When the airplane starts accelerating raise the nose slightly and begin a shallow climb. At this point begin raising flaps 10 degrees at a time until you are clean with normal climb speed. Most low time (and some high time) pilots don’t realize the airplane will fly just fine with full power and full flaps.

Exactly. I used to perform all four fundamentals (straight and level, turns, climbs, descents) with students at full flaps bottom of the white arc, and even a knot or two below the white arc was possible since the bottom of the white arc is the power off stall speed.

For the life of me I can’t understand why you young guys are in such an all-fired hurry to get the nose up to the climb attitude before the flaps are up and trim is reset. Add power and right rudder while pushing the yoke forward. Then begin the flap retraction process, then trim, trim, trim. After your speed is well into the safe range you THEN increase the attitude to that of normal climb. No wonder there are so many botched-go-around fatalities. Stop preaching attitude before speed. All of the above takes maybe five seconds with no danger of stalling and spinning. If you’re already over the runway why would you need to climb immediately anyway? You can spare five seconds for safety.

Dave,

You nailed it. Those that are preaching power up, pitch up are forgetting the inverse effects of power on trim. Add power slowly moving the stick and the right rudder in about the same amount as the throttle moves toward the full power stop. Let the airplane accelerate. Then flaps to 50% (in a Cirrus).

Right, but imagine doing this 36 feet above the ground? It’s no longer a go-around but more akin to a take-off with full flaps. I think there is something lost in translation between the two ideas. Once you zonk the flaps up a notch this low, its seems very similar to me to a soft-field take-off (in the sense the nose has to come down immediately to build lift). And that brings me to the other point of a go-around: Generating lift. That’s the ultimate goal! Not thrust. Lift. I don’t think this nuisance is taught that way to a lot of pilots – I could be wrong.

I was thinking the same thing. My Go Around entails power, right rudder, and pushing forward on the stick – all at the same time! Only when I have gained sufficient speed will I pitch to climb, and then while climbing I will retract flaps.

I practice this maneuver on a regular basis, and I feel safe doing this at 100′ AGL or 10′ AGL.

Good article, John. That’s why aircraft carrier islands are on the right side!

No it’s not! Jets do not create p-factor!

Read an article years back about reasons for right side/left side island placement, can only think of a Japanese carrier or two that put them there, however the right side argument would make sense for a boltering prop plane.

Yes it is. Jets aren’t the only aircraft that operate on carriers.

Airplane’s attitude is actually more important than the airspeed! A airplane can stall at any airspeed but won’t stall until the critical angle of attack is exceeded!

John, excellent article. After a career of flying heavy jets and now in a Bonanza with the G3X Garmin System, go arounds are a particularly sensitive subject. The STC for the G3X requires the TO/GA button to be located where “the hand that adjusts the throttle can find it without delay” ??????? On an airplane with a throttle like large jets the button is almost exclusively located on the end of the throttle where ones thumb makes it natural. My previous panel with the King KFC200 the TO/GA button was on top of the left yoke and felt natural. I personally feel the TO/GA button and its subsequent operation is down the list of things to do. Mine is set for 7 degrees pitch. The Boeing 757 sets go around power to what is required for 2000 FPM – gentle. Not all go arounds are nor all approaches flown with flight directors…it’s called basic instrument flying. You are already flying so just start adding power gently and pitch up naturally…just like when you add power, the nose tends to climb. Too many instructors and too many pilots think a go around is an emergency maneuver … it’s not…it’s just another step in the flight. Do as you described John Wooden…be quick but don’t hurry.

PS. Most pilots that are trained the way I was do not “fly” the flight director but look through it to basic attitude flight.

John,

Good piece. I don’t really see the need to pitch up – but not too much. That will happen just by adding power.

As for hating instant analysis, I get it. Especially on YouTube. Monetizing tragedy. We were conflicted as well but chose to publish our thoughts for only Cirrus fatal accidents on YT once we had defendable facts so we could reach those that are not COPA members. Usually substantiated by a NTSB preliminary report.

Historically and behind our paywall on the COPA Forum we discuss possibilities amongst ourselves initially but loose interest two years down the road when the NTSB publishes their final report. Learning needs to happen while the accident is immediately in front of us.

At the COPA Training Foundation, with our new focus on easily obtainable and anonymized data that we harvest from FlySto and ADS-B we’ve been able to draw parallels to similar accidents already vetted by the NTSB.

Go around fatals all have the same signatures. As do spatial disorientation accidents and landing mishaps.

We live in a world where data is accessible nearly in real time and not only available to the NTSB. Early analysis is a slippery slope to be sure. YouTube is no place to go to learn to fly but, like Air Facts, it is a great place to learn from the misfortune of others. It is the way our regs have been written since day one.

Thanks for all you do.

Chuck Cali

President – COPA Training Foundation

Thanks for all you and COPA do, Chuck. To some extent, the bad accident videos will always be out there, so it’s helpful to have thoughtful counterweights like COPA filling the void.

The “pitch up” part of my 5 steps is more about picking a target pitch attitude than being aggressive with the pitch up (definitely bad). I find that if the pilot has a target attitude in mind, it’s much easier to prevent wild oscillations in pitch. On the other hand, instrument pilots sometimes don’t pitch up enough during a missed approach in actual IMC – in that case, establishing a climb is absolutely essential.

The article gives very bad advice in step 2. It’s the reason why people kill themselves. NO – DO NOT PITCH UP. Planes do not climb due to pitch. Planes climb due to thrust. I mean the advice in step 2 in the very last sentence even says “Be prepared to push forward and start trimming nose-down.” which is entirely contradictory to pitching up. This is what kills. This. It’s not just this but it is mainly this. People don’t understand fundamentally how a plane flies.

And it’s sooo comical that even an article trying to solve the problem perpetuates it. And why is that? It’s because aviation is somehow treated like an art form, and every pilot is an artist. We have no objective standards for how a plane should be flown correctly, only standards for outcomes. And as long as you can fly within the prescribed outcomes like keeping heading or altitude to a margin, you’re golden. No one questions how you do it. There is no objective standard for how to use the controls. How to manage the power. Just artist’s recommendations.

My friend died this year in a go-around. Exactly like this article’s story. EXACTLY. And he didn’t need to had he have been trained properly.

I know what you’re saying Marko, and I think you’re emphasizing a key point, but you absolutely do have to pitch up at some point in the go-around. I wrote “Pitch up—but not too much” to emphasize that it needs to be controlled, and there needs to be a target attitude so it’s a precise maneuver (no artist recommendations, it just depends on the airplane what that attitude is). Note that I did not write “pull back on the yoke” because that’s probably not the right answer in most airplanes. However, adding full power and pushing forward on the yoke will still cause the pitch to eventually go above the horizon. And that’s a good thing… eventually.

“Pitch up—but not too much” is an artist’s recommendation though. It tells the pilot nothing about what they have to do. It’s almost the same as saying “Do something to climb”

I really am writing this comment with the best of intentions. I swear!

Clearly people are dying. Clearly something is wrong that this maneuver is so deadly. And I contend it’s the imprecision with which it is taught. And that includes language.

First of all, like I said, airplanes do not climb due to a certain pitch, they climb due to a certain amount of thrust representing enough(excess) power! This is such an important distinction and why pitch should not be mentioned in the manner you mentioned it and in the manner the FAA handbook does. You can fly and climb with a barn door if you attach enough thrust to it and you can do so in any direction!

So objectively, correctly the go-around maneuver should be taught as:

1. add thrust – go full power to initiate a climb

2. (concurrently to step 1.) anticipate what that will do to the plane and the change in control forces and keep it under control: in landing configuration and trim, expect an excessive nose up pitching moment, expect an excessive nose left yaw, be prepared to push forward on the controls and retrim to maintain level flight, use rudder to balance the ball

3. reduce drag, retract full flaps to partial, retract gear, retract flaps fully

4. (concurrently to step 3.)anticipate what that will do to the plane and the control forces and keep it under control: retracting flaps expect further nose up pitching moment, push forward, retrim and maintain level flight

5. (concurrently to step 1. and 3.) Accelerate to climbing speed, pitch to maintain this speed

I put this together in a few minutes so it’s rudimentary, but it is objective and precise. Level flight and balanced ball, airspeed are objective, we can measure them. The correct affects are described given the aerodynamics of a plane and the correct control inputs are explained. It’s precise.

In step one you cannot go wrong following this instruction. Full power is full power.

In step two you cannot go wrong, you are told that adding full power will have precise aerodynamic effects and which exact control inputs, and to what degree, will be necessary to counteract them to keep the plane under control, a centered ball and level flight are both objective.

In step three you cannot go wrong, changing configuration is objective.

In step four you cannot go wrong, you are told that changing configuration again has aerodynamic effects and which exact control inputs, and to what degree, will be necessary to counteract them to keep the plane under control, a centered ball and level flight are both objective.

And finally in step five as the side track through steps one to four, you cannot go wrong by building AFM declared Vy or Vclimb and then pitching to maintain this speed. Airspeed is objective.

And just to make it absolutely clear: At full power, at Vy or Vclimb what ever the pitch to achieve and maintain this airspeed does not mater. The plane will climb at these AFM declared speeds! You might actually need to pitch down, below the horizon, when on the back side of the power curve to build this speed and climb! Which is why it’s called the area of reverse control! You should not focus on pitch but on speed with the understanding how pitch affects speed! That’s how a plane works! It climbs at a certain power setting and airspeed – not certain pitch! Why?: Because the combination ensures the plane is at the correct angle of attack and has enough excess thrust. Telling people to add pitch is how these people die! Stop it!

And now if you’re going to tell me that this is one way how to teach go arounds and that what I say is not wrong you are again missing the point. The point is this is the only way. What I outlined using my own words, is what needs to happen. It’s not debatable. If you do anything else, approach it any differently you risk losing control of your plane. And that’s an objective fact. I could have possibly used different terms to describe the same objective things, or a different language, but what has to happen in reality to safely execute a go around is exactly what I describe above according to everything we know about aerodynamics!

And my grip is people will argue this. People pretend there are more than one ways to do it or teach it. People will argue that in some planes it’s different. And then people die. Because somehow this is up to debate, artists arguing who has a nicer style, not accepted that no, it’s physics, it works only one way and everyone has to do it the same way to be safe.

First, I am sorry about your friend.

Need to unpack two things you said:

– “Planes climb due to thrust”

That’s right, but it really is *excess thrust* that causing a plane to fly, right? And depending on the plane’s drag will determine how much “excess thrust” you have once you go full power in go-around. In cases where the frame is very slick, the nose will immediately pitch up. and unless you as the pilot take action, you breach the angle of attack and stall/spin. Conversely, in a less aerodynamic frame that has a lot of intrinsic drag, you as the pilot need to pitch up to compensate for the lack of lift you are generating. My point is: It’s not a one size fits all like you are describing.

– Aviation as an art form

I empathize where you are coming from but on the other hand, like in a lot of complex tasks, there are many ways to accomplish them satisfactory. Some techniques are better than others for sure. But be that as it may, many, MANY type organizations teach flying by the numbers (see ABS, MAPA, COPA, etc. etc.) that force discipline in the various areas you mention. Even on how to do a go-around. See Tom Turner’s wonderful video for ABS on whether you should raise flaps vs. gear. Great stuff. (and I’m not even a Bonanza pilot but I still enjoy it!)

First of all, excellent and important article. The go around is arguably the most high performance maneuver that we do in GA outside of acrobatics. It needs to be practiced, well thought out in advance, and respected. A go around is very different in a 172 than a PA-46 so while I appreciate teaching the one size fits all approach, that is a recipe for accelerated stalls and tragedy. As stated numerous times above the most important element is stopping the descent. Don’t just go full power in a high performance plane in landing configuration unless you want to pitch up impressively (and have only a few seconds to fix everything before stalling). I personally go partial power, push while trimming down, and raise gear. I’m cross checking to ensure I’m not slowing or losing altitude. Only then am I incrementally raising flaps and putting in full power steadily but not abruptly. As long as there’s not a significant obstacle (mountain, building…) in front of the runway there’s plenty of time to climb, don’t rush it. Know what your plane does in a go around and practice them both in IMC and VMC. Be careful out there.