Why are spatial disorientation accidents on the rise?

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Spatial disorientation kills. All pilots know this intuitively, but the statistics back up the gut feel: 94% of fixed-wing general aviation accidents involving SD are fatal, a shocking number that hasn’t changed much over the last four decades. So while these accidents make up a small percent of total accidents (see this article for the details), they still make up a significant share of all fatalities.

If those numbers don’t surprise you, this fascinating study from earlier this year should.

More tech, more accidents?

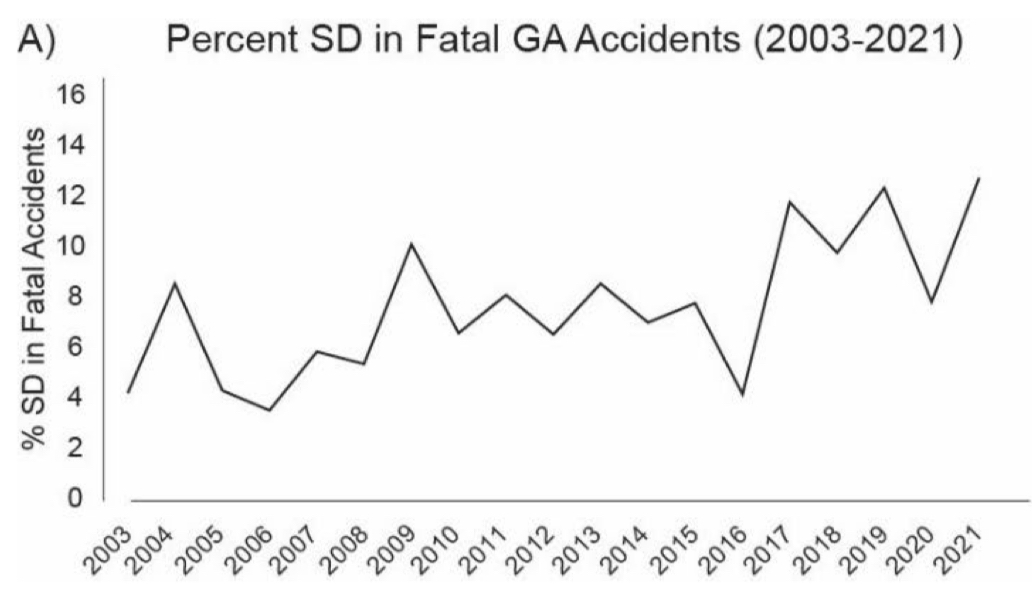

First, the researchers from the FAA show that SD accidents have not declined since 2003—in fact, quite the opposite. You might assume the widespread adoption of tools like datalink weather, modern autopilots, reliable AHRS, and electronic flight bag apps would make VFR-into-IMC (the classic SD accident scenario) much less common. It’s easier than ever to know where the bad weather is, and our avionics are more reliable than in the days of vacuum pumps and ADFs. It’s a great theory, but the numbers don’t support it:

Smart students of statistics may point out that the graph above could be an example of the denominator changing (total accidents) and not the numerator (SD accidents). GA accidents overall and fatal accidents in particular are both down since the early 2000s, so if SD accidents are holding steady, they might make up a higher share of a smaller total. Again, though, the numbers disagree. Fatal GA accidents have declined from an average of 324/year in 2003-2006 to an average of 218 in 2018-2021, a drop of 33%. Over that same timeframe, fatal SD accidents actually increased, from an average of 17 to an average of 24—a 41% rise.

Better technology, but more spatial disorientation accidents. It’s certainly not what I would have guessed.

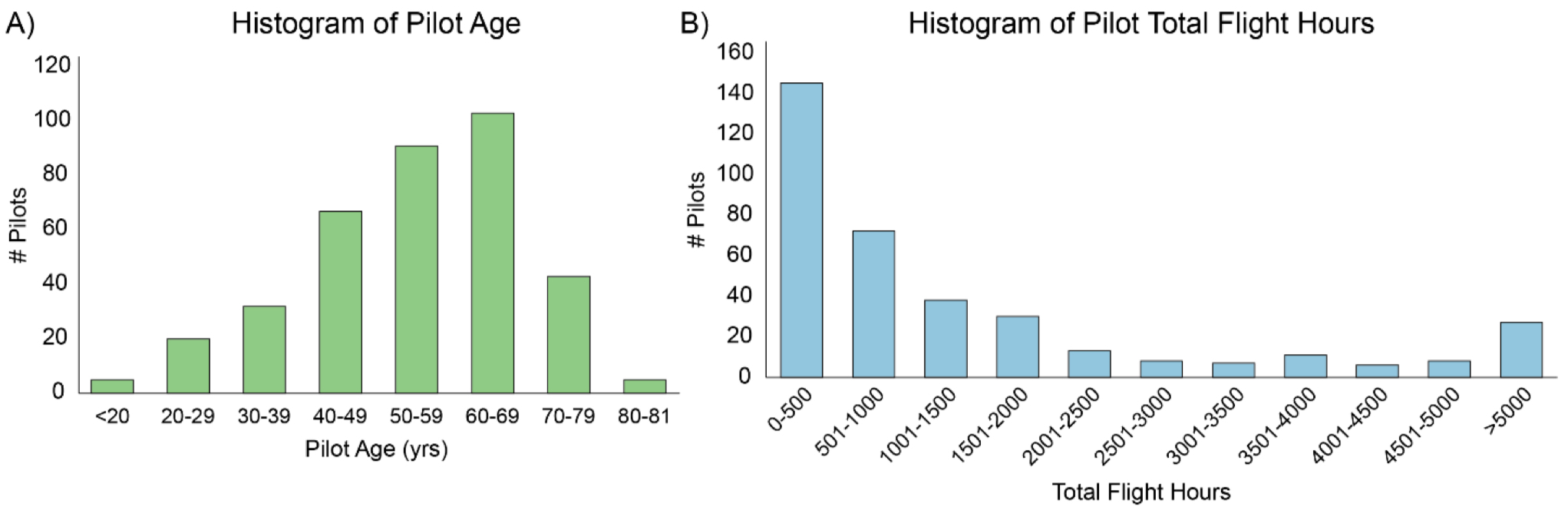

The profile of pilots who are crashing, on the other hand, is what I would have guessed: older pilots and pilots with less than 1000 hours are most likely to end up in an NTSB report for SD.

Pilots between age 50-70 make up only 26% of active GA pilots, so the first graph above might initially seem surprising since over half of the accidents involved pilots in that age range. But remember that most pilots under age 30 are either student pilots, flight instructors, or professional pilots. The GA pilots flying cross-country in marginal or IFR weather, where SD accidents typically occur, are older.

As far as flight hours, we’ve all read about “the killing zone” for pilots between 50 and 350 hours, and you can see that in the blue bars above. More experience does seem to lead to safer flying, at least in this case.

So while you could tell a story about older, less experienced pilots who get in over their heads, the evidence for this is anecdotal at best.

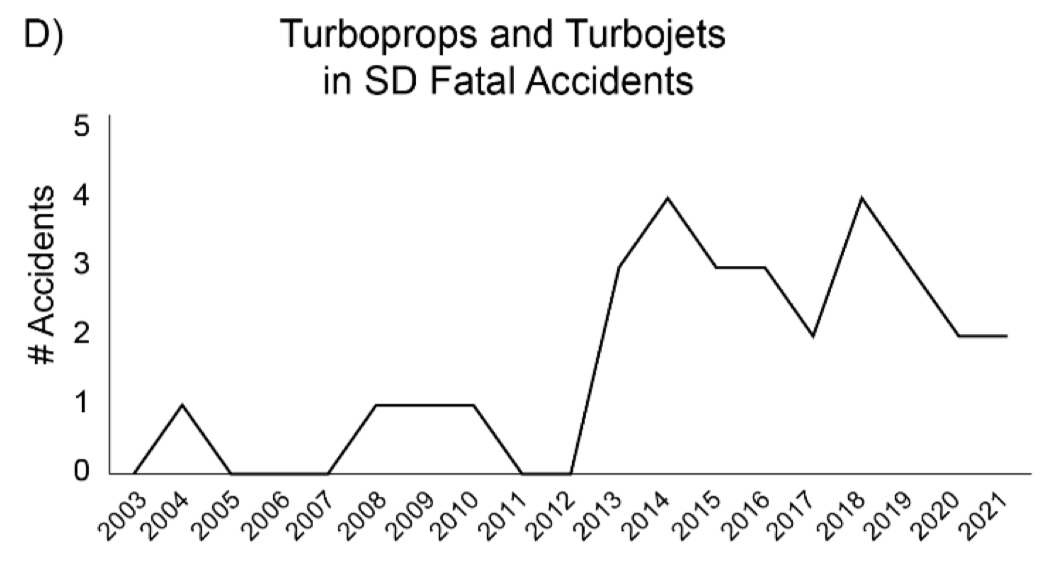

One other detail is definitely part of the picture: the increasing prevalence of turboprops and jets. The numbers are small here, but the trend is certainly worrying over the last decade.

Again, though, for anyone paying attention to FBO ramps lately this makes sense. Single engine turboprops and light jets are booming, while high performance pistons are stagnant. The result is the doctor in a Bonanza 50 years ago is more likely to be a business owner in a TBM these days. Such airplanes are incredibly capable, but they are also high performance machines that can quickly get away from the pilot if they lack proficiency.

An unexpected cause

To review: against a backdrop of falling accident rates, spatial disorientation accidents have risen, and these accidents typically involve older and less experienced pilots, sometimes flying turbine airplanes.

Unfortunately, that’s not the end of the story.

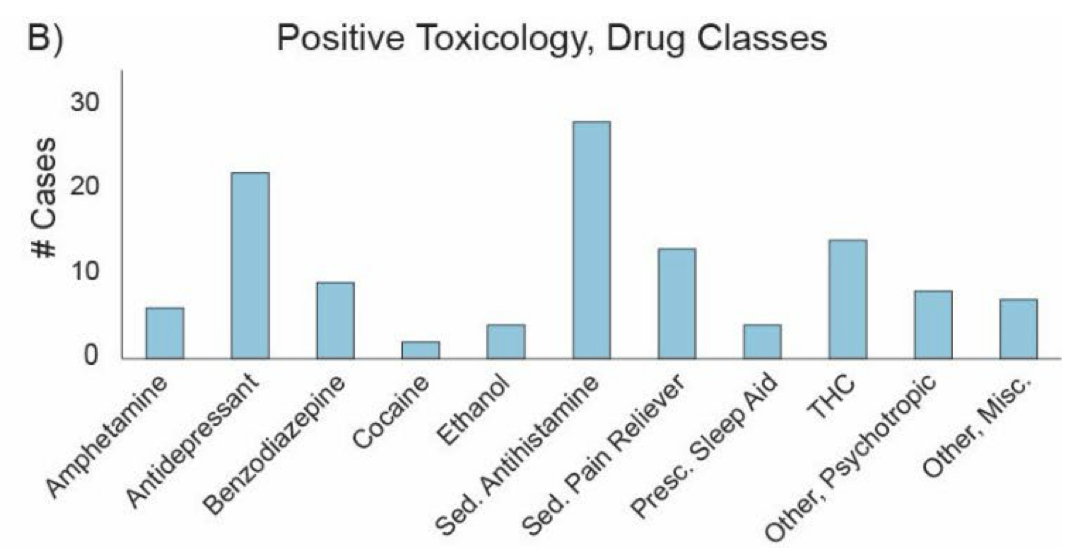

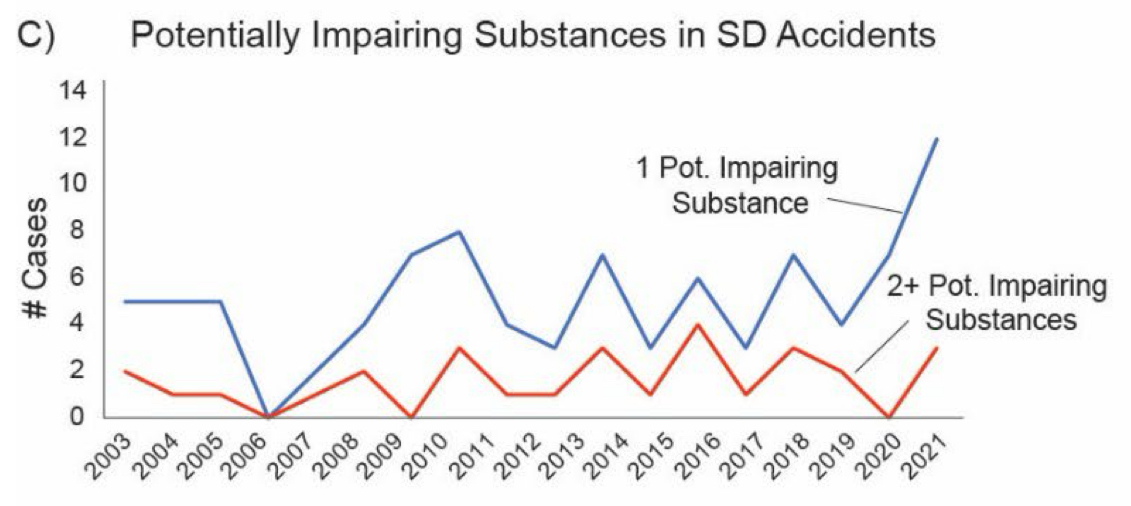

The FAA report also points out the uncomfortable reality that “potentially impairing substances” show up in an increasing number of NTSB reports. In fact, over the 2003-2021 timeframe, “A total of 90 out of 367 (24.5%) fatal pilots had a positive toxicology result.” That one quarter of accident pilots were potentially impaired seems incredibly high, and not something we should sweep under the rug.

These positive toxicology results were almost all drugs, as alcohol was a rare finding. What drugs were these pilots taking? Mostly cold medicine, but antidepressants are a close second, and even THC is creeping up:

Obviously, taking a Benadryl does not lead directly to a fatal accident. But it also does not help a pilot who may be dealing with bad weather or a lack of avionics proficiency. Even worse, the report goes on to explain that “27 accidents included positive toxicology findings for two or more potentially impairing substances… 14 pilots tested positive for an illicit substance.”

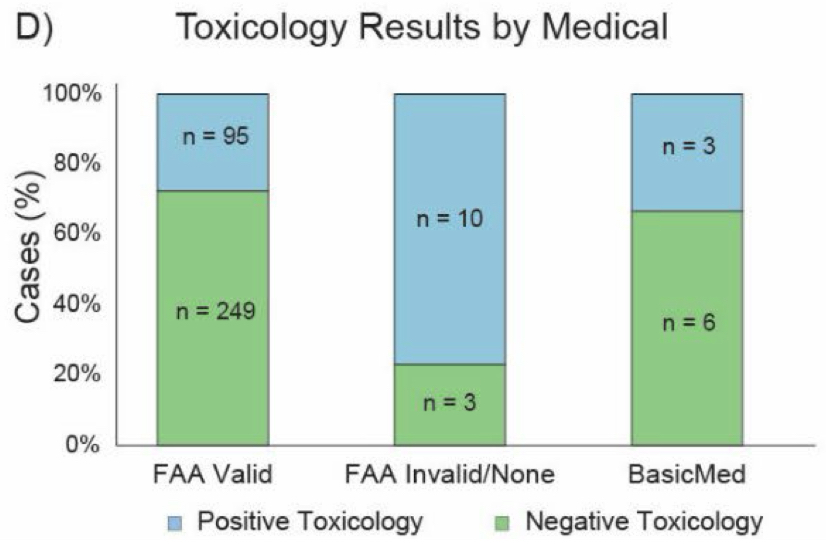

Some of these pilots are probably just rule-breakers by nature. Notice in the graph below that 77% of accident pilots who did not have a valid FAA medical tested positive for toxicology. That suggests these pilots knew they weren’t 100% healthy, and chose to fly anyway. It’s doubtful that a better flight review or a new regulation would change these pilots’ behavior. Even excluding those pilots, though, 28% of pilots with a valid FAA medical tested positive.

What to do

I’m not suggesting pilots cancel every flight when they have a sniffle, or that they resort to a caveman lifestyle and forswear all medications. I have flown with a cold and lived to tell the story, like most pilots. But these results should give us pause. Drugs clearly have an under-appreciated role in SD accidents, and that’s something that is completely under our control.

The FAA actually has a very helpful resource that explains what types of medication can be used by pilots. It’s worth reviewing as we prepare for cold and flu season, because a few minor adjustments can keep you reasonably healthy and perfectly legal. For example, if you have to fly then choose Allegra over Benadryl, Afrin over NyQuil, and Tylenol over Tylenol PM. If you’re taking serious medication like narcotic pain-killers, an honest discussion with your AME is in order.

If you are going to fly when you’re a little under the weather, try to stack the odds in your favor. Fly during the day (the statistics on SD accidents at night are terrible), have a good autopilot (know how to use it!), and consider taking another pilot along (who has been briefed on their role). Remember that Mother Nature does not care about your sinus infection or your bad back.

As sad as the statistics are about drugs, this is not the whole story—after all, 75% of SD accidents did not involve drugs. Also, SD does not necessarily mean VFR-into-IMC. While that is still the most common accident in this category, it accounts for less than 50% of fatal SD accidents. So even if you never take medication, there is plenty of work to do on basic instrument flying skills, avionics proficiency, and weather interpretation.

The NTSB data has been clear for many decades: the pilot in the left seat is the weakest link on a typical GA flight. This is not a reason to quit, it’s a reason to bring our best every time we fly. That means being healthy, unimpaired by drugs, well rested, and most of all proficient. The stakes are high, but so are the rewards.

- Go-arounds don’t have to be hard - December 8, 2025

- Guard frequency in the age of social media - October 13, 2025

- Why are spatial disorientation accidents on the rise? - September 8, 2025

John, you write: “Also, SD does not necessarily mean VFR-into-IMC. While that is still the most common accident in this category, it accounts for less than 50% of fatal SD accidents.”

Fair. BUT, they still make it almost 50% of the accidents in the report. I’d like to highlight two gold nuggets here:

* “Importantly, many of these pilots were briefed or were aware of the weather conditions before the flight and still chose to operate under VFR, regardless, indicating that these accidents were not due to oversights or sudden changes in weather. This is an important area for potential outreach and education within the pilot community that could potentially minimize future SD accidents.”

* “Based on meteorological information in the final NTSB reports, flights were evaluated for cases where a pilot entered IMC while intending to operate under visual flight rules (VFR). VFR to IMC flights made up nearly half of all fatal SD GA accidents in the current dataset (43.9%; n = 161; Figure 5A). Further, the majority of VFR to IMC accidents occurred during the en route portion of the flight (n = 105; Figure 5B). Most pilots involved in these VFR-IMC accidents did not hold instrument rating (n = 127), and the incidence of these accidents was relatively consistent across the 19-year span (Figure 5C).”

So, a few things still hold true:

– Get an instrument rating, the training that is required for the rating can save your life one day, i.e., you never have to fly a single approach and still reap the benefits – and marketing for this rating should probably be realigned to attract more VFR only pilots who think “they don’t need it”

– There seems to be a gap between briefing the weather and understanding its implications, i.e., situations that lead to SD – there be dragons even if convection, high winds, and ice aren’t in the forecast

– Get an autopilot! I know the economics of that suggestion isn’t easy. I get it. I really do. But, if the little blue button could save your life one day, how much is that worth?

For the record: I have gotten SD straight-and-level in the summer, VFR day. I just hit HAZE, leveled off on autopilot, and I was just talking with my PAX and suddenly I felt like the plane was turning (I was moving my head a lot). It is a strange experience for those who have never had it – it’s very visceral and you have to fight to not immediately react to it. Then, you just stare at the instruments, recognize you REALLY ARE not turning, and it just dissipates (not in seconds but in a minute or so, you start to realign yourself and life is good).

Amen to both John and Alexander!

thanks for your article… harder to quantify but I wonder how much low blood sugar and or low oxygen could play into these statistics… sometimes us ‘older’ folks can get relatively hypoxic even at normal altitudes… ie 8000 feet… and I always eat a snack before an approach! …take care

Daryl, totally agree. 8000 feet can totally do you in. Been there, at night, and it happened (just wanted to put my head on the yoke and sleep, not caring what the airplane might do afterwards). Practically begged ATC for lower (6), and the difference between 8 and 6 was instant.

Daryl, or dehydration. Drinking enough water—preferably with electrolytes—is a good idea especially as one is more prone to using up water at higher altitudes.

Alexander: Great comment to supplement John Z’s article. I was wondering how may VFR to IMC SD accidents involved VFR pilots versus IFR pilots. Seems like the majority.

To respond to your action item “get instrument rating”, that is a steep hill to climb for some pilots (time, budget, etc.). I was wondering if there is some structured training we should be thinking about to supplement PPL a little more than we already do. Something that would teach and evaluate instrument scans, upset recovery, and more hood/foggle time, even for those settled in with PPL with no intention of getting instrument rated.

This is a great idea, and I think some real instrument training should be part of every flight review. I also think autopilot usage should be a mandatory topic during initial and recurrent training – so many pilots have a good autopilot but have no idea how to use it. The reality is, if a VFR pilot enters IMC, using the autopilot is probably the best thing to do.

This.

FWIW the GAJSC (General Aviation Joint Safety Committee) has recognized that the traditional training of conducting a 180˚ turn upon an inadvertent entry into IMC (which has been the “standard” since a study conducted in 1957) is WRONG. This 180˚ turn is typically taught by rolling into a standard rate turn. For the TBM pilot cruising at 300 kts a standard rate turn requires an approximate bank of 35˚. It’s no wonder that pilots of these high performance planes are experiencing SD when making a 180˚ turn.

Until the work of the GAJSC on this topic is complete, at least for now, the Airplane Flying Handbook has this to say: (CFIs please take note!) “When a turn is to be made the pilot should anticipate and cope with the relative instability of the roll axis. The smallest practical. bank angle should be used – in any case no more than 10˚ bank angle. A shallow bank takes very little vertical lift from the wings resulting in little, if any deviation in altitude. It may be helpful to turn a few degrees and then return to level flight if a large change in heading is necessary. Repeat the process until the desired heading is reached. This process may releive the progressive overbanking that often results from prolonged turns.”

Great tip, Doug. The 180 so often makes things worse.

Be a check pilot for another pilot working on their instrument rating. Trade off time under the hood. You will learn a lot.

No argument an autopilot is a good tool…until it becomes a crutch. The downside of autopilot use, besides another tool to understand functionality/modes/failures, is if the autopilot can’t cope with conditions (icing, sensor failures) a fat/dump/happy PIC is going to have a plateful dumped into their lap quite suddenly…in other words, it shouldn’t become a means to dig a deeper hole. For it to be a benefit, the PIC must be proficient, not just current, and only using it to relieve fatigue, not to decide it’s a good time to watch the latest streaming downloads, so if it’s about to kick off they see it coming and are already taking action to take back over.

For all the “high net worth” individuals flying the turbines solo, bet there’s at least one CFI out there that would fly for the hours alone.

I wonder what the SD statistics are going to show after MOSAIC has been in effect for a few years.

My cousin is a Breathing Therapist and an advanced EMT. She informed me that a quick method of increasing the blood oxygen level is to consciously “purse” your lips while exhaling, which increases back pressure in your lungs and somehow raises the level of oxygen in the blood. A simultaneous warning sign of hypoxia induced brain fog is an increase in heart rate for no apparent reason as the body automatically works to send more blood to the brain.

I carry a finger insertion type blood oxygen level device in my flight bag and noticed as I aged the onset of mild hypoxia often became evident at altitudes above 5K at night, and above 8K in the daytime. This brain fog was easily confirmed by the blood ox device.

Controlled breathing with pursed lips amazingly works fast to raise blood oxygen percentages above 95, which in my case eliminates any noticeable effects of hypoxia. On shorter flights above 5K, minus bringing along an oxygen bottle, pursing the lips has proven to be very useful.

I fly long distances quite often with O2 above 12to 15k. I like your idea of the pursed lips prior to arrival. I find being at altitude with O2 it still gives me brain fog in the terminal area. I need to be sharper late in the flight

Thx

I am 73 years old commercial pilot, instrument rated and current. Home is Alaska where we get 23 hr darkness in the winter. I fly all 12 months. By my count 75 percent of GA planes up here have vacuum my own plane included. They are not bad people. To stay current and Proficient I fly a lot of practice approaches year around. Frankly, I don’t see a problem in last 50 years with vacuum . I do have a backup electric vacuum pump! Someone pointed out the less weight from getting rid of vacuum, I solve that by going on a diet! Instead.

It’s one thing to be current , however, it another thing to be absolutely Proficient!

Something I didn’t see in this article. 6 approach every six months was never good for me even today. (Just personal min) I am around 42 half are practice with a Safty pilot other for all the marbles in Less then VFR.

Thanks

Jim Gibertoni

Six approaches in six months definitely does not guarantee proficiency – you’re 100% right about that. Especially if none of them are flown in actual IMC.

Typo

75% do not have vacuum

Jim Gibertoni

I notice that one chart list positive toxicology reports and another has the phrase “potential impairment” in the title. There is a very large gap between a known fact and a possible cause.

This calls to mind the struggle OKC has been having for some years in actually keeping up with all the new drugs and their effect on flying. I’m thinking about antidepressant drugs in particularly. In my mind, the drop in the rate of positive alcohol tests and the rise in rates of positive antidepressants tests might be correlated. Treating one drug as bad as the other is probably incorrect. I can’t help but believe, more medically treated pilots are considerably safer than the plague of self-soothing drunks in the cockpit from 1973, when I got my License.

The question is, if the two are related, is a good thing? I think net-net yes.

Pilots struggle with mental health issues, just like every other group of people. And a lot pilots mask their issues with alcohol, While there may have indeed been an 8 hr interval from “bottle to throttle,” that is no guarantee that pilot is fit to fly.

The problem is that FAA OKC just can’t keep up with the advances, not that medical advances are being made.

Reference the Pilot Mental Health Study

https://www.pmhc.org/research

I have an inkling suspicion that for many pilots who end up in SD accidents, are there because they have an overwhelming belief in their new modern avionics and APs to save their bacon if they play too close to the edge of the VMC/IMC envelope. Essentially, the same attitudes of mind that turned turbine-powered luxury panelled glass palaces into the new “Doctor Killers” of our age.

I definitely think you’re onto something with the drop in alcohol but the rise in drugs (with antidepressants probably high on the list). I think most Americans in general take more medication now than they did 30 years ago – that’s not all bad (and lord knows the FAA hasn’t done a good job of reacting to this), but it may not get the attention it deserves from pilots.

As for advanced avionics, they are here to stay. I personally am shocked at how many pilots pay to put in a powerful new autopilot (or spend a lot of money for an airplane with one) and then have no idea how to use it. Avionics proficiency is a critical skill today, not a nice to have. Yes, you have to have good stick and rudder skills, but those two things are not mutually exclusive. If you fly with an autopilot or an advanced GPS, you need to be proficient with it.

Superb, well-written analysis with a powerful message. Having gotten an IFR ticket in 1987 and flying single pilot IFR on a relatively regular basis for the past 38 years in a high performance piston single, I would add that the risk of spatial disorientation in IMC never goes to zero regardless of years of experience doing it. It had been decades since I had experienced SD, but on a 2023 IFR departure out of San Gabriel Valley (KEMT) I got a totally unexpected and overwhelming case of the “leans.” I was flying the somewhat complicated Obstacle Departure Procedure from runway 19 and entered IMC conditions at 1500 feet msl just as I began the climbing left turn to intercept a radial toward the Paradise VOR to the southeast (opposite direction of my intended route of flight to the northwest). In the soup and on the gauges (glass cockpit EFIS, actually) ATC called traffic ahead and mile (also IMC) and told me to continue my climbing left turn, then in addition told me to expedite to 6000 feet for terrain (the San Gabriel mountains, to be exact). So I pulled up a bit harder and kept turning left, hand-flying the unexpected course and climb directions since there was not time to reprogram the autopilot settings. After about 45 seconds of this combined upward and lateral acceleration my brain told me I was actually wings level and not climbing any more, even though the EFIS showed a 30 degree bank to the left. It wasn’t until I had blown through my new assigned heading and ATC called to say “I’m showing you still in a left turn” that I apologized, corrected and reversed the trend with a turn back to the right. In the midst of this sensory struggle, I was just about to key the mic and tell ATC I had some spatial disorientation when I popped out of the marine layer at 4200 feet and suddenly keeping the shiny side got much easier. I have always adhered to the mantra of “die by your instruments, not the seat of your pants” but when you begin to get close to actually doing that, it is pretty sobering. Especially after years of being relatively comfortable flying in IMC conditions.

I had a person at Oskosh ask why my airplane did not have gyros installed, suggesting that a person would be crazy to fly without them. I pointed out to him that the lack of gyros prevented me from trying anything stupid.

IFR training by itself does not solve the VFR into IFR problem. One must be very current and, more importantly, have a plan when moving into instrument conditions. Rolling along in declining VFR conditions expecting to pull up into the clouds to save the day does not meet those criteria.

I strongly encourage VFR pilots to receive IFR training so they are more comfortable and fly more accurately being “on the gages” for heading,turns, climbs, descents, while at altitude. I found this takes 4-8 hours dual, depending on the pilot. Why should they do this? Until they can manage this phase, they are highly subject to SD and loss of control when flying VFR in hazy weather. When flying cross country in ground reported VMC conditions, we sometimes find ourselves able to see the ground below, but not ahead, which means NO VISIBLE HORIZON. Being on Flight Following is great, only if the PIC can control the plane in such conditions. Often these same VFR pilots are then motivated to pursue the IFR rating for the benefits it provides.

Most pilots do not take SD seriously until they actually experience the condition. The very hopeless and SUDDEN confusion must be produced by the instructor during a training flight for the student fo appreciate the gravity of SD

As a pilot that has been through private pilot and instrument I thing the FAA should come up with a new level for instrument training/certification that doesn’t require a check ride or currency requirement nor would it give the rights to fly into IMC. The training both written and with a CFII would be of value to a private pilot and increase safety and reduce risk when accidentally caught in IMC.

My research on these type accidents indicates many of these pilots are not proficient hand flying in IMC. When George quits the accident is a foregone conclusion.

Always enjoy your writing John. Thank you for all you do in our community.

Could hyperventilation be playing a role here?