|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

FOREWORD

While this article concerns airline operations, it can still be of value to the general aviation instrument pilot in three ways. First, it will give the general aviation pilot a glimpse into the cockpit of a commercial airliner. Second, it will provide insight into what airline pilots do on a daily basis. And finally, it is a lesson in weather forecasts—the lesson being to trust, but verify! So, I will open the cockpit door and let the reader take a peek inside my former place of employment.

THE GAMES BEGIN

It all began one Saturday morning in about 2013 when I departed San Francisco (SFO) for Denver (DEN) flying a Boeing 757. It was my leg to fly, and while the 0540 departure caused my hair to hurt, the flight to DEN was uneventful. At Denver, we switched airplanes to a Boeing 767-300 for the flight back to SFO.

The weather in the Bay Area was perfect VFR and forecast to remain that way for the rest of the day. This meant our fuel load was relatively light as we did not need an IFR alternate. Our planned landing fuel was just 12,000 pounds, or about an hour in cruise flight.

However, while parked at the gate in Denver, I checked the ATIS for SFO one last time before pushback and was startled to see the weather was now 200 overcast with ½ mile visibility in fog. This changed everything! I quickly sent a message to my dispatcher bringing the new weather situation to his attention and asking him to file me an IFR alternate. This he did by assigning our alternate as Oakland, a mere three-minute flight from SFO, which legally did not require any additional fuel.

In spite of this, I ordered an extra 5,000 lbs of fuel to be boarded for possible holding. As previously mentioned, the B-767-300 burns about 12,000 lbs of fuel per hour (1,800 gallons per hour), so even this wasn’t a lot of extra fuel.

As we taxied out for takeoff at Denver, we got the latest SFO weather from our dispatcher and found it had deteriorated even further to ceiling zero, visibility 1/16th of a mile in fog with an RVR of 800 feet. Incredibly, this was above our landing minimums, so we didn’t sweat it. And of course, RVR stands for Runway Visual Range, which is the horizontal visibility measured in feet by instruments located next to the runway.

The flight to SFO was uneventful until we contacted NORCAL approach control. The controller told us we could expect the FMS Bridge Visual Approach to Runway 28 Right. A visual? Obviously, the weather had improved dramatically. We then uninstalled the ILS 28R approach from our flight management computer and installed the FMS Bridge Visual Approach, and pressed on.

As we got closer, the controller subsequently informed us that there had been several go-arounds from the FMS Bridge Visual Approach in the past few minutes and asked us what our lowest landing minimums were. My first officer told him, “We’re good down to RVR 300 feet.” The Runway 28R Category IIIb minimums were RVR 600 feet, which meant our B-767 had lower landing minimums than what the airport was certified for.

In airline operations, ceiling is never a factor, and when the visibility gets real low, the ceiling is almost always zero, which we don’t care about since our minimums are based solely on RVR.

At all major air terminals, RVR is measured at three points along the runway: touchdown, which covers the first one-third of the runway length; midfield, which covers the middle one-third of the runway; and rollout, which covers the last one-third.

About 30 miles out, we could visually see that the entire San Francisco Bay Area was bathed in bright sunshine except for the first 1/3 of Runways 28 Left and Right, which were blanketed by a thick but very localized fog bank. The NORCAL controller told us to expect the ILS 28 Right approach and that the RVR was now 600 feet for touchdown, unlimited for midfield, and unlimited for rollout. This was a very bizarre combination of RVR readouts!

We were now forced to conduct a Category IIIb “autoland” approach with the autopilot flying the approach and making the landing. Pilots are only legal to hand-fly the airplane down to RVR 1,800 feet, and any visibility below that requires the autopilot to fly the approach and make the landing. It also requires the captain to be designated as the pilot flying.

With well-practiced hands, we reinstalled the ILS approach into our FMS computer, and I took control of the airplane from my first officer. The controller then unexpectedly started vectoring us for the approach much sooner than we had expected. This was due to the fact that the two airplanes ahead of us were not legal for RVR 600 and were sent packing. We were now number one for the approach instead of number three, which really pressed us for time.

To program the airplane for a Category IIIb autoland approach, and brief it, is an involved procedure that takes some time. But we finally got everything set up, and with all three autopilots flying the airplane, we intercepted the localizer for Runway 28 Right.

About 10 miles from touchdown we could see the entire airport, the terminal, and even our gate area basking in bright sunlight. In addition, we could see that airplanes were taking off unimpeded on Runways 1 Left and 1 Right. However, the first one-third of our runway was still shrouded in dense fog, with the rest of the runway plainly visible.

Flying in clear blue skies and brilliant sunlight, we entered the tops of the fog at 300 feet AGL and went on solid instruments. However, our three autopilots were doing their usual superb job of keeping the airplane precisely on the glideslope and localizer. Less than a minute after entering the fog, the radar altimeter’s synthetic voice called out “Fifty” feet, but the runway was not in sight. Then we heard “Thirty” feet and we caught our first glimpse of the runway centerline lights.

At 30 feet, my first officer called out “Idle engaged” as the autothrottles pulled both throttles to idle, followed by “Flare engaged” as the autopilot began the flare maneuver by raising the nose. I could now see just two of the 150-foot-long runway stripes ahead, which meant the actual RVR was approximately 300 feet. However, this was just enough of a visual cue to tell me that the autopilots had flared too high and were about to totally botch the landing—which they proceeded to do!

With all three landing gear firmly on the ground, I disconnected the autothrottles and put both engines in full reverse thrust. At this point, the autopilots were still steering us perfectly down the centerline at 140 knots with visibility between 300 and 400 feet—well below the advertised RVR of 600 feet. This made it the lowest visibility instrument approach I had ever flown, and it was thrilling!

But the thrill was short-lived when, 2,000 feet after touchdown, we rolled out of the gloomy fog bank and into bright sunlight, which rudely assaulted our eyes. At 80 knots and with eyes squinting, I disconnected the autopilot and brought the engines out of reverse. The rest of the landing rollout and taxi to the gate were perfectly normal—unlike the damnedest instrument approach I had ever flown!

After setting the parking brake at the gate and shutting the engines down, I got on the PA and tried to explain to my 200 passengers that the lousy landing was made by the autopilot, and that it was not my fault, but the asphalt.

I could almost hear them say in unison, “Sure, buddy, that’s what they all say,” and like Rodney Dangerfield, I got no respect!

POSTSCRIPT

The hard landing was not the airplane’s fault, but really was the asphalt, along with some undulations in the runway surface in the touchdown zone. The first part of Runway 28R protrudes out into San Francisco Bay and is built on a pier, not on solid ground. Because of this, just after the 1,000-foot touchdown markers, there is a rather well-pronounced dip in the runway caused by thousands of landings by heavy airplanes over the years which has compressed the asphalt. This dip is then followed by a rise, then the pavement levels off.

I always tried to land before this dip, since landing in the touchdown zone—like you are supposed to—meant your dual truck landing gear would impact the upsloping pavement just beyond the dip, resulting in a firm landing. But our three radar altimeters didn’t know this. They were tricked into flaring too low thanks to the dip, followed by climbing due to the rise in the runway surface, which totally upset the landing maneuver.

Normally, the autopilots make very nice landings, even in a crosswind. The silver lining in the hard landing meant job security for human pilots—the last link in the technology chain. It is fortunate that the aviation technology gods do not currently recognize the term airmanship!

The Category IIIb ILS Autoland Approach

The information presented may not be current since my last ILS Cat lllb Autoland approach was in 2014. But everything below was current when the video (below) was filmed in 2008.

WHAT IS AN ILS CAT lllb AUTOLAND APPROACH?

It is an instrument approach where the autopilot flies the approach, makes the landing, and steers the airplane on the runway centerline after touchdown. A Cat lllb ILS Autoland approach has minimums of 300 feet RVR. Unlike Cat I approaches, Cat lllb ILS Autolands do not have a Decision Altitude as minimums are based solely on RVR. And when the RVR gets that low, the ceiling is almost always zero.

WHAT IS RVR?

It stands for Runway Visual Range and is measured in horizontal feet by transmissometers located at 3 places along the side of the runway. They consist of a light beam projector and a light beam receiver. At most airports,

even with only a Cat 1 ILS approach, there are three transmissometers, one that measures visibility in the touchdown zone, or the first one third of the runway, a second one at midfield or the second third of the runway, and one in the rollout part of a landing or the final third of the runway.

WHEN DO WE MAKE AN AUTOLAND APPROACH?

There are only three occasions when we let the autopilot make the approach and landing. They are;

- When the Runway Visual Range (RVR) in the Touchdown zone is less than 1800 feet.

- In VFR conditions for training when a new captain is being supervised by a company instructor during Initial Operating Experience, or IOE.

- For the airplane’s currency. The airplane must make at least one Autoland every 50 days. If no autolands have been made in 50 days, maintenance technicians must test all equipment required for an Autoland and once that is done, the airplane is recertified and the calendar is reset.

Many people erroneously believe the pilots let the autopilot make every landing. This is patently untrue as autolands are exceedingly rare events that require very special conditions.

WHAT IS REQUIRED TO FLY A CAT IIIB AUTOLAND?

The Pilots—The pilots must make at least two Autoland approaches in the simulator each year to maintain currency. One approach is to the RVR minimums your airplane is certified for, and results in a landing. The second one includes a failure of some navigation equipment that requires a missed approach from less than 200 feet AGL. The captain must be the pilot flying during all Autoland approaches.

The Airplane—To be legal for a Cat lllb ILS Autoland approach, the airplane must be equipped with at least the following equipment;

- Three autopilots

- Three ILS receivers

- Three radar altimeters

- Three flight control computers

- Auto throttles

- Auto brakes

- Three independent electrical systems

- An operable and running APU, or Auxiliary Power Unit which is a jet engine located in the tail equipped with the same generator as found on the engines.

- Three generators

There are more subsystems required but these are the primary ones.

NOTE: some of today’s Technically Advanced general aviation airplanes have an Autoland feature, but it is not to be used, and is not certified for, ILS Cat lllb Autolands. They are for emergency use only.

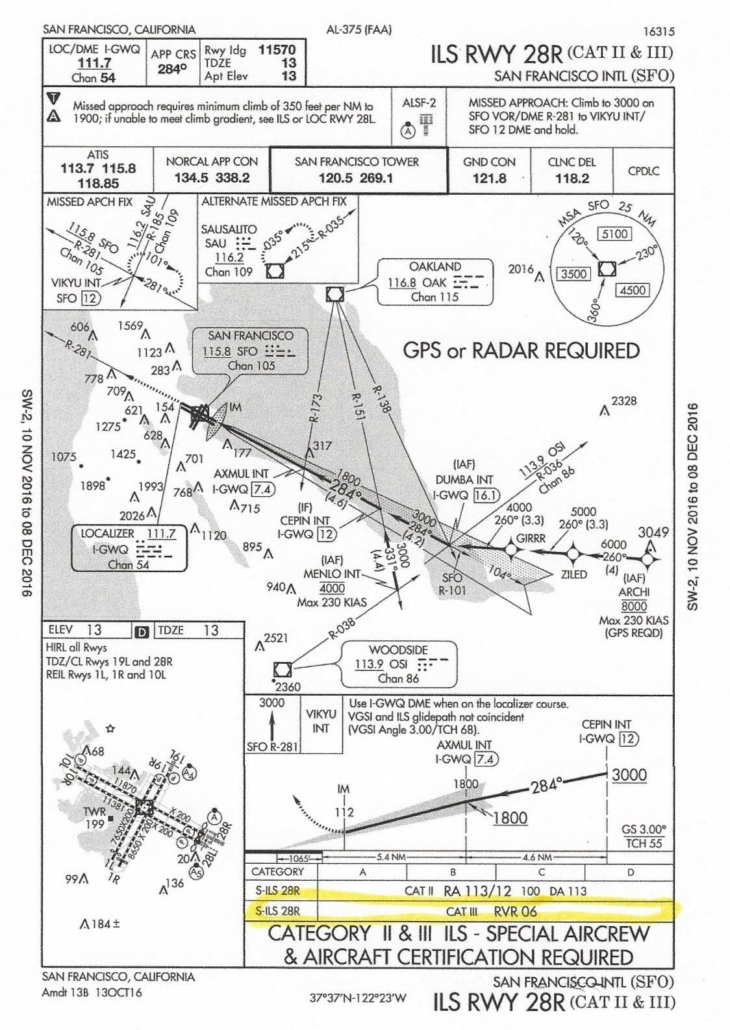

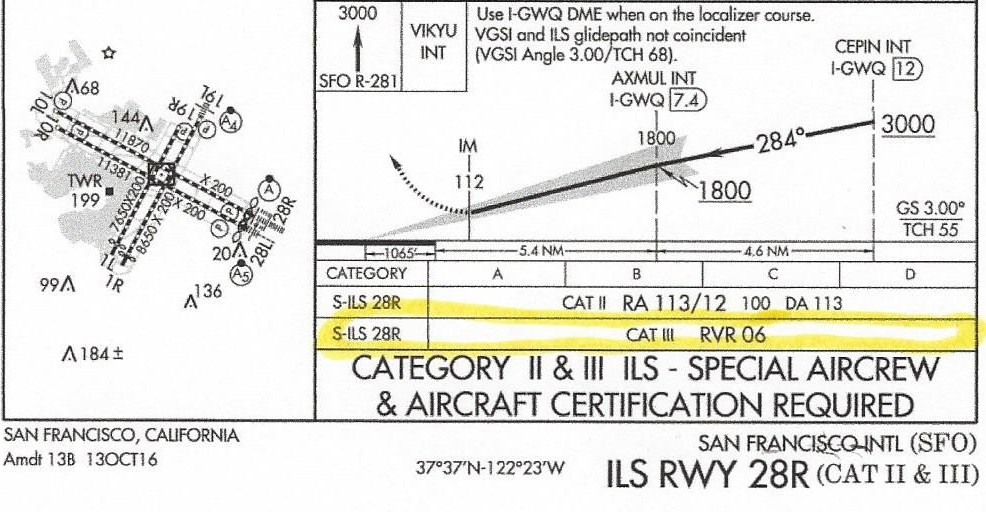

The Airport—Not all airports are certified for Autoland approaches. The instrument approach chart must list Cat llla or Cat lllb minimums to be legal for an Autoland. Pilots cannot arbitrarily make an Autoland approach at just any airport. Below is an example of an airport, KSFO, that is legal for an Autoland approach since Cat llla and Cat lllb minimums are listed.

This approach is for the ILS to Runway 28R at KSFO, which is the approach being flown in the attached video. Notice that the minimums for Cat lllb are an RVR of 600 feet. The Boeing 757 I am flying in the video is certified down to RVR 300 feet. This means my airplane had lower minimums than the airport which, with three exceptions, is true for every airport.

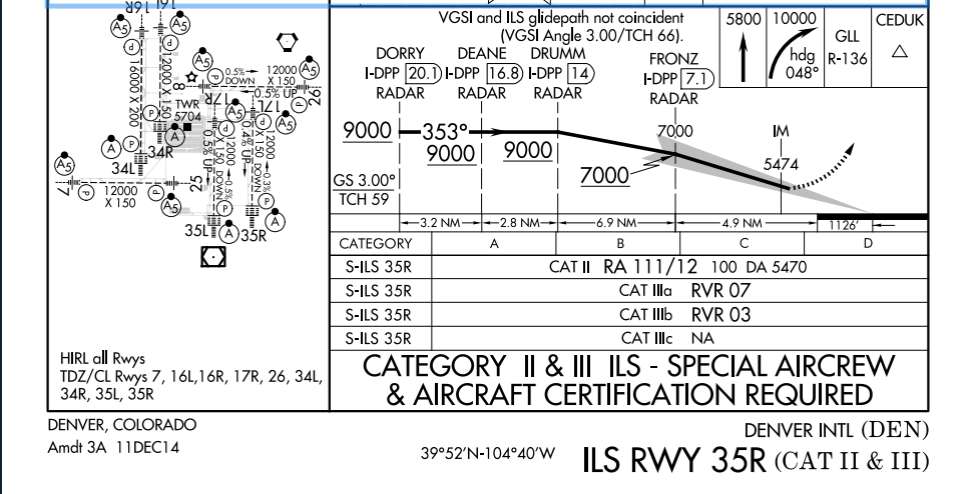

There are only 3 airports in the country that have minimums of an RVR of just 300 feet, and they are Denver, Seattle, and Atlanta. Most of the other airports have RVR minimums of 600 feet, as with the ILS to RWY 28R at KSFO.

For an airport to be certified for Autoland approaches, they must have localizers and glideslopes with extreme accuracy. And the accuracy to allow for Autolands down to an RVR of just 300 feet means that accuracy is even more extreme, which is why there are only 3 airports with this capability. Notice in the remarks on both approach charts below where it says SPECIAL AIRCREW AND AIRCRAFT CERTIFICATION REQUIRED, which is explained above.

Notice on the Denver approach chart below for RWY 35R, not only are Cat lllb approaches authorized, but Cat lllc approaches as well with minimums listed as NA. This means if you are trained for it, and your airplane certified for Cat lllc Autolands, your minimums are zero zero! Denver is the only airport in the country where you could legally land with zero visibility. The only problem with that is how do you find your gate after clearing the runway?

The airport must first be configured for autolands prior to pilots being cleared to fly one. Here is what is done.

- The ILS critical line, with its red ILS sign off to the side and double yellow stripes across the taxiway well short of the normal runway hold short lines, must be activated. This is done by the ATC ground controller with instructions for taxiing airplanes to hold short of that line. Keeping airplanes behind this line protects the glideslope signal from being corrupted.

- The airport’s backup emergency generator is started and the approach lights, ILS transmitter, runway boundary and centerline lights are powered by the generator. If the generator fails, power instantly reverts back to the normal commercial power source. Approach lights are not required for Cat lllb ILS Autolands, but runway centerline and boundary lights are.

When making an Autoland in VFR weather either for fun, training, or for airplane or pilot currency, the crew must first advise the approach controller of their intention of making an Autoland. The approach controller then advises the tower controller who activates the ILS critical area hold short line and keeps all taxiing airplanes behind it until the plane making the Autoland clears the runway after landing.

Not advising ATC, and then conducting an Autoland has led to accidents. There was a crash at (maybe) KLAX where the pilots conducted and auto land without first advising the approach controller of their intent. Because of this lapse, there were airplanes holding short of the runway well ahead of the ILS critical line. As the plane neared the threshold, the glideslope started oscillating and the autopilots followed those oscillations which upset the landing maneuver causing the plane to crash.

Now Let’s FLY a Cat lllb ILS Autoland

Here is what the crew does when cleared for an ILS Cat lllb Autoland approach based on United Airline’s procedures as of 2015. It also explains everything we do in the attached video. In the video, we will be flying the ILS 28R to KSFO in a Boeing 757. It was filmed in about 2008 using an analog video tape recorder that my first officer placed on the glareshield, and not with an electronic device.

The weather as stated on the ATIS was a ceiling of zero with an RVR of 600 feet (minimums) in the touchdown zone and 1,000 feet in both midfield and rollout. While being vectored to intercept the localizer, we started the APU, armed the left and right autopilots, and programmed the approach into our FMS. As required by the regulations, I was the captain flying. Since the weather was a localized fog bank with tops at around 300 feet, we were flying in VMC above the fog when the approach controller assigned us a heading to intercept the RWY 28R localizer.

While flying with the center autopilot engaged and the left and right autopilots armed, we intercepted the localizer and the left and right autopilots activated. Now, all three autopilots began tracking the localizer. Even though the autopilots are flying the airplane, I am required to keep my left hand on the control wheel and my right hand on the power levers, ready to instantly take over manually if something critical to the approach might fail, especially below 200 feet AGL.

At precisely 1,420 feet radar altitude, we heard several relays click in the electrical panel behind us. This indicated that the electrical system had automatically split into 3 independent systems. The left side of the electrical system was now powered by the left generator, the center was powered by the APU generator and battery, while the right side was powered by the right generator.

Next, my first officer calls out “500 feet” at which time we verbally assure that the flaps are at 30 degrees which is the normal setting for landing. This call also assures that we are properly configured for a stabilized approach.

Her next callout is “Approaching Alert Height” which is 200 feet based on the radar altimeters, and it tells us we are getting close to the runway.

Her next callout is “Alert Height” which means we are at 100 feet AGL and still in solid IMC going 140 knots. You will catch a momentary glimpse of the runway lead-in strobe lights, which we are not required to see for landing. Alert Height is where the captain scans the entire instrument display looking for red flags. If there are no discrepancies, I say “Land Three” meaning that everything is in order for a Cat lllb Autoland.

Just as the runway threshold comes into view, the synthetic voice from the radar altimeters says tersely “Fifty!” as in fifty feet AGL. My first officer, watching her pilot flight display screen, announces “Flare Engaged” which means the autopilots have begun the flare maneuver. She then announces “Idle Engaged” which means the autothrottles have reduce engine power to idle for landing. Her next callout, as seen on her PFD screen is “Rollout Engaged” which means the three autopilots will begin steering the airplane precisely on the runway centerline after touchdown

After landing, I put both engines into full reverse thrust, but leave the autopilots on until I hear my first officer say “80 Knots” which is when I can disconnect all thee autopilots. This I do and take over steering onto the high speed taxiway using the rudder pedals and nosewheel steering.

As can be seen in the video, the autopilots make a rather firm landing. This is not the airplane’s fault, but is caused by a dip in the runway surface in the touchdown zone which for Runways 28 Left and Right at KSFO, is built on a pier that sticks out into San Francisco Bay. Because of this, thousands of landings have created a dip in the runway surface. The autopilots follow this dip downward, then upward on the other side of the dip which totally upsets the normal flare and touchdown maneuver resulting in a firm, but safe landing.

It is vitally important to hear my first officer’s comment after touchdown when she says “Yours are much smoother”. This is an indication that I had trained (indoctrinated) her well…Just kidding!

- A Very Close Call - December 10, 2025

- The Strangest Instrument Approach I Have Ever Flown - August 20, 2025

- Revenge at 4,000 Feet - July 23, 2025

This whole article is amazing Joel! Well done! Maybe one day this technology will come to GA too?

Concise explanation on how these approaches are planned , practiced and executed. I didn’t realize KDEN has everything but the ability to get to the gate ..well done , thanks

Would get something similar at NAS Whidbey on Puget Sound…Rwy 7 and tower (arrival end of 7) socked in by fog bank off Sound to/below minimums…approach end numbers for Rwy 25 visible 30 miles out. ATC at field, not knowing any better would set up for Rwy 7 IFR arrival, we’d check in and request visual 25…sometimes easier is better, of course it was “our field” so “requests” were usually honored.

The CAT IIIA, B and C terminology is a great example of ideas that have changed but just won’t die. Sure enough, the latest approach chart for KDEN 35R, which is over ten years old, shows minimums for CAT IIIA, B and C. But the chart for KDEN 35L, updated only seven years ago, shows only minimums for CAT II and CAT III…no A, B or C. In fact, the FAA has no advisory material referencing these categories today, and hasn’t for quite a few years.

The currently operable distinguishing terminology is “fail-passive”, a system which can be approved for landings down to TDZ RVR 600 and requires runway visual reference prior to touchdown, and “fail-operational”, which can be approved down to TDZ RVR 300 but does not require actual runway visual reference prior to touchdown. A fail-passive system requires a missed approach in the event of a single failure. A fail-operational system can continue the approach with a single failure. Although the CAT IIIC idea was around for quite a while, it was never approved for scheduled airline use, and no one even thinks about it anymore largely because of the limitations of ground facilities…as you said, how do you get to the gate?

Autolanding, as well as most of any lower landing minimum program, is op-spec and equipment dependent. At AA, the standard procedure on the 737 for a CAT III fail-passive approach, to as low as TDZ RVR 600, was autopilot off at 1000 feet. The rest of the approach all the way to touchdown was hand-flown, using the autothrottle and the HUD, which came complete with annunciations for “flare” and “rollout”, etc. And the autothrottle retards all by itself at precisely 27 feet based on radio altitude, which means 27 feet above whatever bump or dip in the runway you happen to be over, as opposed to 27 feet above the part you will touch down on!

Brought back memories, well written. In 32+ years at United I never did an autoland on the line, only in Sim. Retired off the B-777 (most of my career was on the B-727) in Sep. 2001. Yes, I managed a “trip” immediately after 9/11 before retiring (age 60 then).

A well written article that gives some nice insight into what airline flying can be like. Might I suggest, however, that since it’s been a while since you’ve been in the airline world, having the article fact checked might have been a good idea. There are actually quite a few errors, which I’m sure you’d prefer to have correct in the article. As an example, adding OAK as an alternate does require alternate fuel (it’s listed as 10 minutes of fuel on our flight plans). Also, since SFO is limited to 600 RVR, you could not conduct an approach to 300 RVR, even if you and the airplane are certified for it. For the 3 airports listed where an approach is available below 600 RVR, it’s actually the improved SMGCS lighting (surface movement guidance control system) for the runway exits and taxiways that allows lower visibility operations, not any improvements in the glideslope or localizer. When a CAT IIIC approach lists “NA”, that means “not authorized”, which does not mean you could fly an approach with zero visibility. The APU is not required for autolands (it is considered best standard for the 767 because of how the EFIS screens would blank below 200 feet with the failure of a generator, but it’s not required). In fact, only 2 generators are required for the 767 for a CATIII approach. I could go on, but I think you get the idea. And for what it’s worth, in 30 years of being based at SFO, I’ve never noticed the dip in the 28s you mentioned, but I’ll look for it on my next trip…

p.s. Whether or not the camera was analog or an electric device, I hope your F/O is also retired! I know the flight office and the FAA wouldn’t be impressed by one of the operating pilots filming a CAT III approach.

KMEM has 300 ft RVR mins on 36L, 36R, and 36C.

KMEM has 300 ft RVR mins on 36L, 36R, and 36C.

I have over 9000 hours in the 757/767 and a multitude of CAT 2/3 approaches. I flew the MD-11 for 9 years and I have a total of 6 CAT 3 C (now changed to just CAT 3) approach and landings to RVR 300 feet and ironically all of them were ATL 8 L. At our touchdown cockpit height of 43 feet I could see, very fuzzily, one centerline light when we felt the mains touchdown. I was asked once why we couldn’t land with zero visibility? Simple, we needed the 300 feet to see how to turn off the runway. I have a Bonanza now with all glass but like I told someone recently…before I HAD to go…now I don’t.

Cat 3 in Amsterdam many years ago, arriving non stop from Singapore after various problems en route from Russian ATC we were not overloaded with fuel in my B747-412. The Dutch weather not promising, ceiling and RVR 150metres. Yes most airlines use metric for RVR not feet. So a Cat3B approach was briefed, and as Captain, my job to conduct the approach and landing. My beautiful Boeing autopilots produced a splendid ILS approach and landing, we rolled gently to a stop , then cleared the runway on the designated taxiway and became completely lost. No dedicated leading in taxiway lights as in SIN and LHR, just a few feet of gray tarmac. The B744 was 230feet long and 212feet wide, so not a good idea to wander about on an unfamiliar bit of real estate., admitting failure we called for a leader car to escort us to our gate. One arrived, flashing amber lights otherwise resembling a New York cab, but not as speedy and we reached our gate some 20 minutes after landing. Slow, maybe, but we didn’t hit anything which is the whole point of civill aviation.However I must admit to a minor sin two days later, preparing my airplane for our flight to JFK. Airport security being intended to prevent flight crew from doing their ground inspection before departure, Schipol dispatcher provided departing crew with a large key which gave access from the passenger tunnel to a ladder leading to the ground. Simple, yes, but not so simple when we{me} had failed to return said massive key to the dispatcher. Deciding as a crew that it might be difficult to hsndover the key as we were passing 30W we said nothing. Our return crossing in another airplane was to Frankfurt, so we heard nothing more, as far as I know this key is lurking in the crew seat of MB forever.

I’ve often wondered… given the resolution and accuracy of the radio altimeters and the definitely-not-guaranteed-to-be-flat nature of the terrain on final approach, I’d expect the displayed RA value to bounce all over the place… does it? Many airports have low profile housing, roadways and natural variances in ground elevation all the way to the runway threshold. If even small slopes like the asphalt sinking @SFO fooled the autopilots into flaring too soon, how on earth do pilots/autopilots use the RA readout on approach/short final. Or do they?

What an interesting experience – something probably never conceived for testing during a simulator currency check. When you said some aircraft were sent packing, did you mean sent to another airport or just had to go missed and returned to SFO? Was 1L/1R used for landings while this condition existed?

Fascinating stuff Joel. Thanks!