|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In every life, there are a myriad of “firsts.” Some are quite memorable—your first kiss, pulling out of the dealership in your first new car, or holding your first child. Remember Roberta Flack’s song, The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face?

In aviation, there are memorable firsts too: that first flight when you catch the flying bug; the first solo, slipping the surly bonds all by yourself; your first VFR flight plan that unexpectedly ends up in IMC; or your first precision approach where you spot the runway right at minimums.

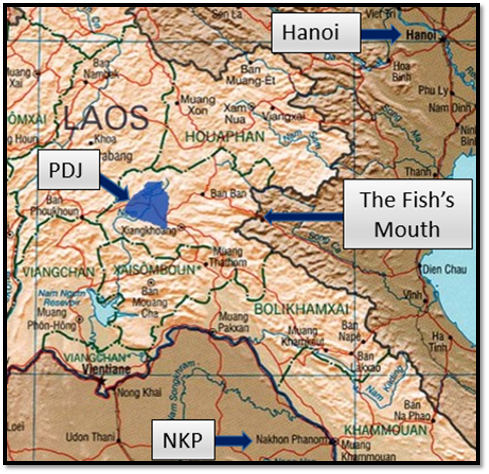

I have my own memorable aviation firsts. In October 1972, I flew my first combat mission in Southeast Asia. I was in the back seat of an OV-10 Bronco on an orientation flight out of Nakhon Phanom (NKP) Air Base in Thailand, flying with an experienced Forward Air Controller (FAC) over Laos. It was an introduction to the combat environment, local procedures, and the terrain I’d soon be navigating on my own.

The OV-10 was a great airplane, but it wasn’t pressurized or air conditioned. The heat and humidity could be brutal, and dodging anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) didn’t exactly help with comfort levels. I figured I could handle it, but I was definitely apprehensive—okay, very apprehensive. Still, I trusted the experienced front-seater beside me, so I wasn’t panicking.

I followed along as we filed our flight plan, got the weather and intel briefings, and picked up our charts. Then we suited up—helmet, parachute harness, survival vest, personal weapons and ammo, signal flares, survival radios, and spare batteries. We stopped by the squadron to grab our binoculars and headed to the Bronco.

Binoculars were a vital FAC tool, especially when flying at 5,000–6,000 feet AGL. The enemy was highly skilled at camouflage, so spotting anything required serious visual work. Our binoculars were kept in hard leather cases for protection, only coming out once we were airborne.

As useful as they were, binoculars were also a pain—literally. They were heavy, and using them meant flying the airplane with one hand. The mic switch was on the right throttle—down for intercom, up for radio—and with five radios on board, one free hand was essential.

The trick was to cradle the binoculars upside down in your right hand, leaving the left for flying and comms.

My front-seater showed me a trick: cradle the binoculars upside down in your right hand, leaving the left for flying and comms. He also warned me never to put the leather strap around my neck—if we had to eject, the binoculars would whip around and beat me senseless. Good tip.

What he didn’t tell me was how looking through binoculars while “jinking” could make you sick.

Jinking meant flying unpredictably to throw off enemy gunners. Every five seconds or so, we’d stomp a rudder pedal to skid the Bronco, then reverse direction. That “five-second rule” matched the approximate time of flight for the AAA rounds they fired at us. As long as we were over enemy territory, we jinked.

So why does jinking while using binoculars make you queasy? It’s a classic case of sensory mismatch. Your eyes show the world spinning below you, while your inner ear—the vestibular system—senses something different. Add in the fact that I wasn’t the one jinking (and couldn’t anticipate the inputs), and my brain decided I must have been poisoned. So it tried to fix the problem by initiating a good old-fashioned barf.

After about two hours airborne, my body had had enough. I didn’t have a barf bag, so I grabbed the leather binocular case and held it close, hoping I wouldn’t ruin it with my first case of airsickness. Fortunately, the break helped, and I managed to avoid hurling.

Lesson learned: if you’re not flying, take periodic breaks from the binoculars.

That said, I did get airsick once—but for a different reason.

After checking out as a FAC, I was assigned to take a new guy on his first combat mission. His name was Frank. We hit it off right away and remain close friends to this day.

One night, the squadron gathered in our “hootch” (really just a bar), which we called the Nail Hole—home to the Nail FACs. There were games of poker and darts going, guys shooting pool, and plenty of adult beverages flowing. I had more than a few myself.

We were waiting for the next day’s flight schedule. When the scheduler walked in and pinned it to the bulletin board, we all gathered around. No names—just call signs and times. I saw “Nail 49” (mine) paired with “Nail 95,” meaning I’d have a back-seater. I didn’t know who 95 was until someone tapped my shoulder. I turned around and saw someone unfamiliar.

“You Nail 49?” he asked.

“Yes, I am.”

“I’m Frank—Nail 95. Guess we’re flying together tomorrow. It’ll be my first combat mission.”

I shook his hand and said I was looking forward to it. Frank looked at my beer and gently suggested I might want to get some crew rest. He wasn’t wrong. I told him to meet me at the O Club at 0730 for breakfast.

Over breakfast, we got to know each other. Frank had flown T-33s for a year after pilot training before volunteering for SEA. As we went through the same pre-mission routine I’d once experienced, I warned him about the binocular jinking effect and told him to bring a barf bag.

Over breakfast, we got to know each other. Frank had flown T-33s for a year after pilot training before volunteering for SEA. As we went through the same pre-mission routine I’d once experienced, I warned him about the binocular jinking effect and told him to bring a barf bag.

We launched. The mission was quiet, but somewhere between breakfast and last night’s drinks, my stomach revolted. I finally turned to Frank and said, “Remember that barf bag I told you to bring?”

“Yeah, it’s stuffed in my flight suit.”

“Can you pass it up here?”

He laughed as he handed it forward—and not a moment too soon. After using it, I felt better and we finished the mission.

The next day, we flew together again, this time to northern Laos. The weather was bad—low visibility and smoke. Despite that, I spotted a heavily loaded truck. It was rare for them to move during daylight, but they must’ve thought the weather would keep us grounded. They guessed wrong.

I called Cricket—our Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center—and requested fighters. Soon, two A-7s checked in. I briefed them, marked the target with a rocket, and cleared them in. The first bomb hit under the truck but failed to explode—insufficient time of flight. The second hit short. The driver probably needed a change of clothes but kept going.

Suddenly, Frank shrieked over the intercom, “WE’RE GETTING SHOT AT!”

“WHERE?” I yelled back, equally high-pitched.

“RIGHT BELOW US!”

I looked down and saw a stream of 23mm airbursts, maybe 100–150 feet below. I told the A-7s and tried to find the gun, but with the poor visibility and no tracers, we couldn’t pinpoint it. The gun eventually stopped firing, likely hoping we hadn’t spotted its location.

We turned our attention back to the truck. The lead A-7 rolled in again. As I turned to watch through the canopy, a tracer from a 37mm gun streaked between me and the wingtip—less than 20 feet away.

I instinctively keyed the mic and let out a string of non-radio-appropriate words: “F#W@Z $@T%!!” Then added, “Lead, you’re cleared hot!”

Lead dropped a 500-pound Mark 82 bomb. It hit right under the truck—and the truck disappeared in the explosion. These bombs didn’t always detonate due to time-of-flight issues, but when they did, the results were spectacular. I watched through the canopy as the fireball bloomed, and what had once been a fully loaded vehicle was now a smoking hole in the road.

Lead dropped a 500-pound Mark 82 bomb. It hit right under the truck—and the truck disappeared in the explosion. These bombs didn’t always detonate due to time-of-flight issues, but when they did, the results were spectacular. I watched through the canopy as the fireball bloomed, and what had once been a fully loaded vehicle was now a smoking hole in the road.

Climbing out, the pilot asked, “Nail, why did you say what you said when you cleared me to drop?”

“A tracer went by the canopy!”

“By my canopy?”

“Would I have said what I said if it had gone by your canopy?”

“Gotcha!” he laughed.

The 37mm gun didn’t fire again. Maybe the operator decided discretion was the better part of valor—thanks again, Bill Shakespeare.

Frank and I debriefed and headed back to the Nail Hole for a couple of drinks. We still laugh about our “Sky King” moment—normally calm and cool voices suddenly replaced by screeching falsettos.

It was a first for both of us.

- (Mis)Adventures in the Birdbath - July 30, 2025

- A First Time for Everything - June 30, 2025

- Throttle Mismanagement: A T-38 Lesson That Stuck - May 14, 2025

Similar story from the Navy OV-10A side, same timeframe: I (Pony 14) flew with VAL-4, Black Ponies in the light attack role. June 30, 1971 I took LT(jg) Steve Salsman on his first in-country flight. It was a routine flight of two armed patrol checking in sectors looking for targets of opportunity. We found a hot one with ARVN troops in contact and coordinated with the troops their position and where they wanted us to place our ordinance. On our second run a loud sound was heard. Steve asked me, “What was that?” I knew but answered, “Don’t worry about it.” We continued to provide close air support until we were ‘winchester’ and headed back to Binh Thuy. Maintenance post flight inspection found where we were hit. The hole was just below the canopy and just forward of where Steve’s knee would have been at the time. Airframe mechanics found the bullet, drilled a hole in it, made a neckless using an inner strain of parachute chord, and presented it to Steve as his Purple Heart because he had a small scratch from aircraft skin shrapnel under is right eye! Steve made it through the rest of his tour with no further close calls in spite of intense missions to the U Minh forest. It saddens me to say that Steve perished in an aircraft accident on his next assignment as a flight instructor in TA-4s.

Like the old admiral said at the end of The Bridges at Toko Ri, “Where do we get such men?”

As an observer in our FAC Cessna Skymaster, while in Korea (1970) ,WE INADVERTANTLY FLEW NORTH OF THE RIVER INTO THE 14MILE SWATH OF A no fly zone.. R.O.K. Rapcon informed us of our miscalculations and scrambled 2 ,R.O.K. F-86 with sidewinders to “escort” us in a 180′ maneuver as a Mig was coming at us at 12 o’clock from North Korea, waiting for us to cross the threshold of their airspace. Glad to live to tell about it!

Back during my 1991 WestPac deployment to MCAS Iwakuni, Japan, when we’d fly our F/A-18’s over to Korea to do some training, sometimes we’d make high-speed runs North towards the P-518 “DMZ” and then do a hard 180-degree turn back South just prior to reaching the line. I’m sure it made the North Korean’s a little antsy to see 4 F/A-18’s doing 0.98 mach headed Northbound. ;-)

My older brother was stationed at Iwakuni from ’73 to ’74 flying F-4Js. I was stationed at Vance as a T-38 IP and he left his Dalmatian Blue 911 Porsche with me to keep it in a garage that I rented from a neighbor (I rented another one from her where I parked the ‘Vette that I bought when I came home from SEA). He asked that I take it out once in a while and ‘stir the oil’, which I was glad to do! I also wondered if the OSI (Office of Special Investigations — the special AF police) were going to call me in and see how I was driving a Porsche and a ‘Vette on 1st Lt pay!!!